Team awarded 2.5 million CPU hours on NSF-funded supercomputer to conduct research

Credit: University of Houston College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences

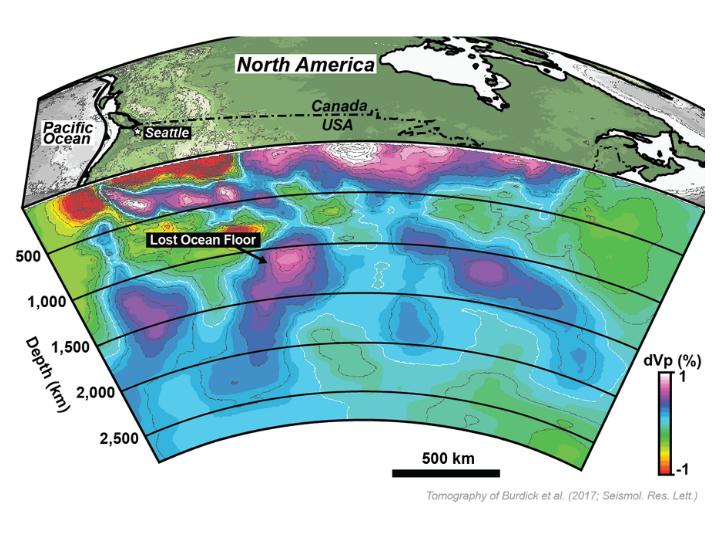

Over 621 miles below the western United States lies what geologists believe are the remains of a lost ocean, sinking toward the center of the Earth. These fragments of the Earth’s crust formed the westernmost portion of North America during the Mesozoic Era, but researchers don’t have a clear explanation of their origin.

A team of geoscientists at the University of Houston led by Lorenzo Colli, assistant professor in the UH College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, has been awarded 2.5 million Central Processing Unit (CPU) hours by the National Science Foundation for use of its high-end computing system, Stampede2, to investigate this “geologic conundrum.”

Stampede2, the flagship supercomputer at the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC) at the University of Texas at Austin, is considered one of the most powerful in the world. It provides scientists computing resources vital to achieving research goals. The monetary value of these awarded resources is more than $2 million. That amounts to one year of continuous research – priceless for Colli and collaborators Jonny Wu, assistant professor, and doctoral student Spencer Fuston in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences.

The UH researchers will ¬use Stampede2 to simulate mantle convection, or the churning of hot ductile rocks in the Earth’s deep interior, through geologic time, which will take them back 230 million years ago to the Triassic period.

“We can build a plate reconstruction that we think fits where this ‘lost ocean’ is positioned, and how long the remains have been there,” Fuston explained. “Then the supercomputer will simulate our plate reconstruction all the way to the present day and will allow us to compare against what the Earth’s mantle looks like in present day.”

This information could help address heated debates related to the configuration of lost ocean basins that were present offshore in western North America during the time of dinosaurs. These topics are key to mineral and hydrocarbon exploration.

“The research will also allow us to improve our models and better understand how the Earth’s interior behaves,” said Colli. “In the long term, the data will help us in dealing with earthquake forecasts and assessing the risk of earthquakes.”

###

Media Contact

S. Sara Tubbs

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/