Research reveals role unusual quantities of protein PRC1 plays in genetic errors

Credit: Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

TROY, N.Y. — An over-abundance of the protein PRC1, which is essential to cell division, is a telltale sign in many cancer types, including prostate, ovarian, and breast cancer. New research, published online today in Developmental Cell, shows that PRC1 acts as a “viscous glue” during cell division, precisely controlling the speed at which two sets of DNA are separated as a single cell divides. The finding could explain why too much or too little PRC1 disrupts that process and causes genome errors linked to cancer.

“PRC1 produces a viscous frictional force, a drag that increases with speed,” said Scott Forth, an assistant professor of biological sciences and member of the Center for Biotechnology and Interdisciplinary Studies at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. “The friction it produces is similar to that of water – if you try to move your hand through water slowly, you move easily, but if you push your hand fast, the water pushes back hard.”

At the nitty-gritty level of DNA, motor proteins, and microtubules, biology takes its cue from physics. During the mitotic stage of cell division, a single cell must copy its DNA into two identical sets, and then rapidly and efficiently pull that DNA apart into two new daughter cells. It’s a physical act, and the cellular structure that does it, the mitotic spindle, is a machine that uses mechanical forces – push, pull, and resistance – to complete the task.

“We think the force PRC1 produces is integrating and dampening out cellular motions as the DNA is separated so that ultimately, you get the correct rate of chromosome segregation,” Forth said. But if the process goes awry, the cells end up working with the wrong instruction manual, which can lead to the uncontrollable growth of cancer.

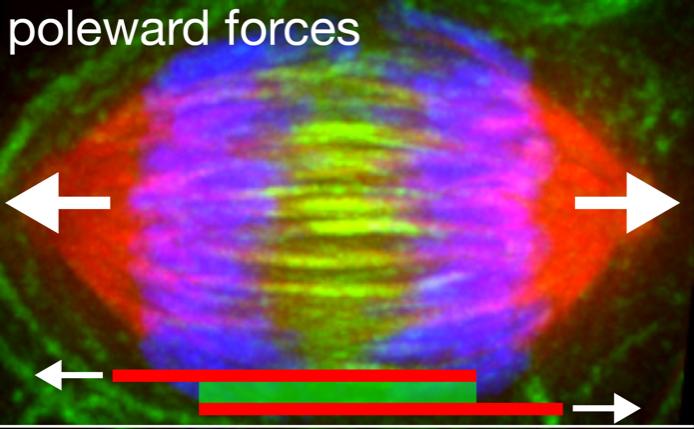

The Forth lab examines the physical forces exerted by components of cellular structures like the mitotic spindle. The spindle is formed when two centrosomes, take a position on opposite sides of the two newly created, and hopefully identical, sets of chromosomes massed near the center of the cell. A dense network of microtubules extends from the centrosomes, forming a cage that surrounds and connects the chromosomes. Then the microtubules – aided by millions of proteins and motor proteins – begin to shorten and slide, pulling the chromosomes toward the centrosomes, until the two sets have been separated.

PRC1 is a “cross-linker,” a long, springy molecule with a head at either end that links two microtubules along their length. Near the center of the mitotic spindle, large quantities of PRC1 link groups of microtubules into bundles.

Forth’s team created a controlled version of the microtubule sliding mechanism in the lab and used an optical trapping technique to measure the frictional force PRC1 exerts between the sliding microtubules. Optical trapping relies on a tightly focused laser beam which attracts an object – in this case, a miniscule polystyrene bead – attached to the microtubule. The researchers use the laser beam to pull on the bead – similar to the “tractor beam” of science fiction – and convert the shift in refracted light as the bead resists the pull of the trap into a direct measure of force.

The team also tagged PRC1 with a fluorescent molecule, allowing them to observe its shifting movement and distribution as the microtubules were pulled apart. They used total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy to collect images of the experiment while simultaneously recording the forces.

Forth and his colleagues found that, as more of the protein is added into the system, the microtubules meet more resistance as they move faster. Essentially, PRC1 behaves like a glue holding the cell together.

“Like a lot of biological processes, it’s a bit of a Goldilocks problem,” Forth said. “If you don’t have this protein, you’re in trouble, because the cell fails at division. If you have too much, we think that it gums up the works and holds everything together too much, which may be how this protein is linked to cancer. There’s a sort of sweet spot in healthy cell division, where there’s just the right amount controlling the rates carefully and precisely.”

“This research reveals the inner workings of a fundamental mechanism of biology, providing knowledge that better positions us to defeat cancer,” said Curt Breneman, dean of the School of Science. “It’s a carefully and beautifully designed study, the results of which have created a foundation on which future anti-cancer strategies can be built.”

“The mitotic crosslinking protein PRC1 acts like a mechanical dashpost to resist microtubule sliding” was published in Developmental Cell. Forth was joined in the research by RPI graduate students Ignas Gaska, April Alfieri, and RPI undergraduate student Mason Armstrong.

###

About Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

Founded in 1824, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute is America’s first technological research university. Rensselaer encompasses five schools, 32 research centers, more than 145 academic programs, and a dynamic community made up of more than 7,900 students and over 100,000 living alumni. Rensselaer faculty and alumni include more than 145 National Academy members, six members of the National Inventors Hall of Fame, six National Medal of Technology winners, five National Medal of Science winners, and a Nobel Prize winner in Physics. With nearly 200 years of experience advancing scientific and technological knowledge, Rensselaer remains focused on addressing global challenges with a spirit of ingenuity and collaboration. To learn more, please visit http://www.

Media Contact

Mary Martialay

[email protected]