Credit: © Olivier Telle/CSH/CNRS

What if more inclusive urban planning for poor populations was key to fighting dengue fever? This is what researchers from the CNRS, the Institut Pasteur and the Indian Council of Medical Research (1) have demonstrated using a geographical approach applied to the greater city of Delhi (India). Their study is published in the journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases on 11 February 2021.

Dengue is a viral disease with no specific treatment or vaccine and a potential threat to 3.5 billion people today – a number that could increase with the urbanisation of tropical areas and global warming. The tiger mosquitoes that carry the disease are particularly well adapted to urban environments and their range is increasingly spreading toward temperate regions.

Since 1996, Delhi has been hit by a dengue epidemic every year between July and November. To find out where and how to take action to better combat these epidemics, a team of geographers, virologists, entomologists and epidemiologists studied their spread throughout this metropolis of 16.7 million inhabitants. Scientists targeted 18 neighbourhoods in Delhi where they measured the abundance of mosquito larvae and looked for the presence of antibodies (a sign of past infection) in a portion of the inhabitants. By combining this field data with cases identified in hospitals, they were able to highlight the role of social and environmental factors in the spread of this emerging disease.

The first finding? Despite a lower mosquito density, affluent neighbourhoods are almost as affected by dengue fever as disadvantaged neighbourhoods, and more so than middle-class neighbourhoods. Scientists explain this paradox by the importance of day-to-day mobility in the city: privileged and disadvantaged neighbourhoods are now hyper-connected and share living spaces as much as viruses. Second: lack of access to running water is the major risk factor for dengue fever infection, more than poverty, although the two are often associated.

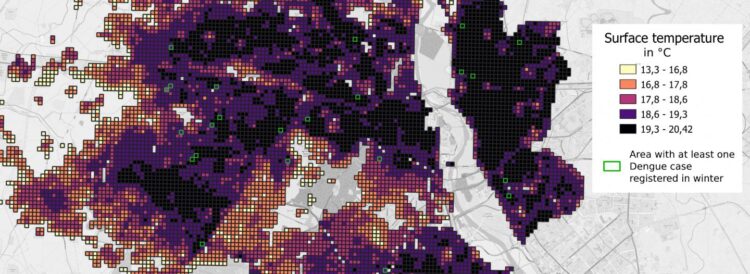

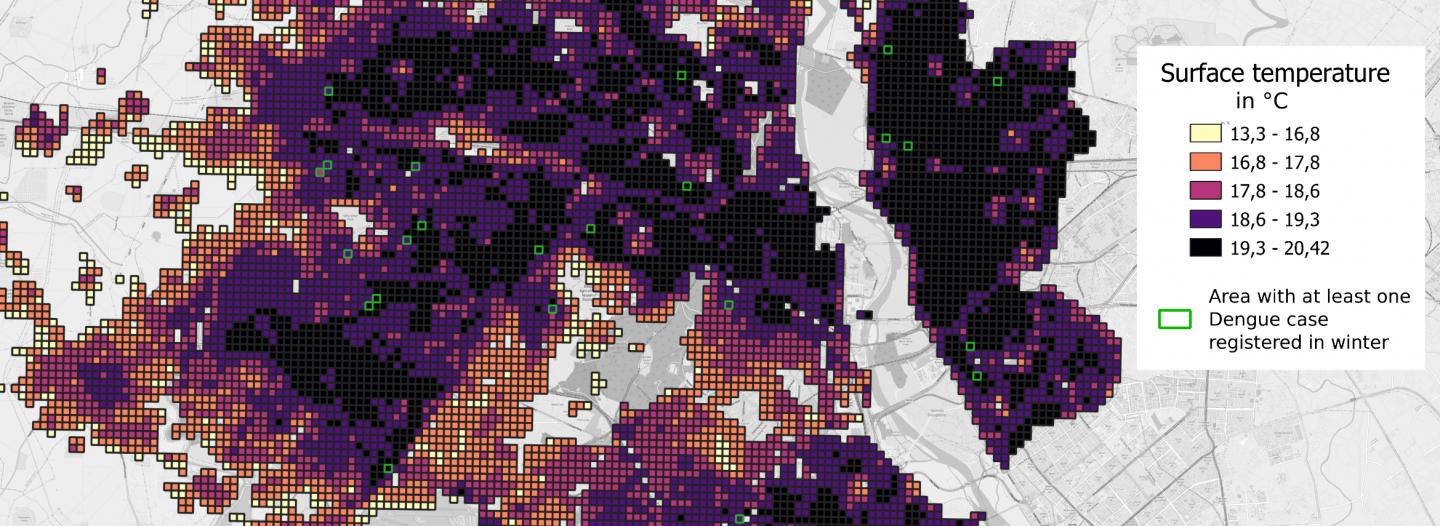

Indeed, the rare winter cases of dengue fever are found in disadvantaged and densely populated neighbourhoods. A lack of running water forces inhabitants to store the water in tanks, which are ideal nesting places for mosquitoes, and the high density of these types of neighbourhoods creates heat islands. Temperatures in these areas reach up to 15°C in January (10°C higher than in less densely populated areas), allowing mosquitoes to survive the winter and continue to spread the virus locally.

In sum, while travel seems to explain the spread of the virus during epidemics, social factors play a dominant role in anchoring the virus in Delhi, since the virus continues to circulate at low levels in winter in dense neighbourhoods with little access to water. Improving access to water in these neighbourhoods should therefore make it possible to mitigate the epidemic throughout the city, and for all its inhabitants. Limiting heat islands, or at least concentrating mosquito control efforts there in the winter, would also weaken the reservoir that feeds the epidemic each year. Urban planning could thus be an instrument in the fight against dengue fever and, more generally, a major lever for improving the health of all. This is a concept that largely predates vaccination and that allowed to control cholera epidemics in European cities in the 19th century.

###

Notes:

(1) The research centres involved are the Centre de sciences humaines (CSH) in Delhi (CNRS/Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères), the Evolutionary genomics, modeling and health laboratory (CNRS/Institut Pasteur), the National Institute of Malaria Research (Indian Council of Medical Research) and the Geographie-cités laboratory (CNRS/Université Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne/EHESS/Université de Paris).

Media Contact

Véronique Etienne

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.