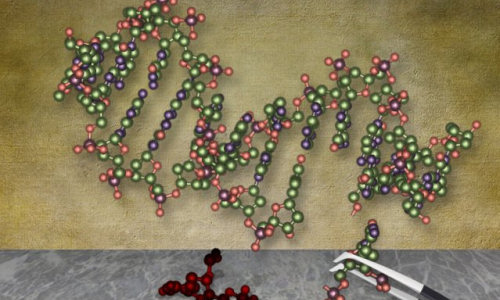

Researchers reverses a liver disorder in mice by correcting a mutated gene.Using a new gene-editing system based on bacterial proteins, MIT researchers have cured mice of a rare liver disorder caused by a single genetic mutation.

Illustration: Christine Daniloff

The findings, described in the March 30 issue of Nature Biotechnology, offer the first evidence that this gene-editing technique, known as CRISPR, can reverse disease symptoms in living animals. CRISPR, which offers an easy way to snip out mutated DNA and replace it with the correct sequence, holds potential for treating many genetic disorders, according to the research team.

“What’s exciting about this approach is that we can actually correct a defective gene in a living adult animal,” says Daniel Anderson, the Samuel A. Goldblith Associate Professor of Chemical Engineering at MIT, a member of the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, and the senior author of the paper.

The recently developed CRISPR system relies on cellular machinery that bacteria use to defend themselves from viral infection. Researchers have copied this cellular system to create gene-editing complexes that include a DNA-cutting enzyme called Cas9 bound to a short RNA guide strand that is programmed to bind to a specific genome sequence, telling Cas9 where to make its cut.

At the same time, the researchers also deliver a DNA template strand. When the cell repairs the damage produced by Cas9, it copies from the template, introducing new genetic material into the genome. Scientists envision that this kind of genome editing could one day help treat diseases such as hemophilia, Huntington’s disease, and others that are caused by single mutations.

Scientists have developed other gene-editing systems based on DNA-slicing enzymes, also known as nucleases, but those complexes can be expensive and difficult to assemble.

“The CRISPR system is very easy to configure and customize,” says Anderson, who is also a member of MIT’s Institute for Medical Engineering and Science. He adds that other systems “can potentially be used in a similar way to the CRISPR system, but with those it is much harder to make a nuclease that’s specific to your target of interest.”

Disease correction

For this study, the researchers designed three guide RNA strands that target different DNA sequences near the mutation that causes type I tyrosinemia, in a gene that codes for an enzyme called FAH. Patients with this disease, which affects about 1 in 100,000 people, cannot break down the amino acid tyrosine, which accumulates and can lead to liver failure. Current treatments include a low-protein diet and a drug called NTCB, which disrupts tyrosine production.

In experiments with adult mice carrying the mutated form of the FAH enzyme, the researchers delivered RNA guide strands along with the gene for Cas9 and a 199-nucleotide DNA template that includes the correct sequence of the mutated FAH gene.

Using this approach, the correct gene was inserted in about one of every 250 hepatocytes — the cells that make up most of the liver. Over the next 30 days, those healthy cells began to proliferate and replace diseased liver cells, eventually accounting for about one-third of all hepatocytes. This was enough to cure the disease, allowing the mice to survive after being taken off the NCTB drug.

“We can do a one-time treatment and totally reverse the condition,” says Hao Yin, a postdoc at the Koch Institute and one of the lead authors of the Nature Biotechnology paper.

“This work shows that CRISPR can be used successfully in adults, and also identifies several of the challenges that will need to be addressed moving forward to the development of human therapies,” says Charles Gersbach, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering at Duke University who was not part of the research team. “In particular, the authors note that the efficiency of gene editing will need to improve significantly to be relevant for most diseases and other delivery methods need to be explored to extend the approach to humans. Nevertheless, this work is an exciting first step to using modern gene-editing tools to correct the devastating genetic diseases for which there are currently no options for affected patients.”

To deliver the CRISPR components, the researchers employed a technique known as high-pressure injection, which uses a high-powered syringe to rapidly discharge the material into a vein. This approach delivers material successfully to liver cells, but Anderson envisions that better delivery approaches are possible. His lab is now working on methods that may be safer and more efficient, including targeted nanoparticles.

Wen Xue, a senior postdoc at the Koch Institute, is also a lead author of the paper. Other authors are Institute Professor Phillip Sharp; Tyler Jacks, director of the Koch Institute; postdoc Sidi Chen; senior postdoc Roman Bogorad; Eric Benedetti and Markus Grompe of the Oregon Stem Cell Center; and Victor Koteliansky of the Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology.

The research was funded by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institutes of Health, and the Marie D. and Pierre Casimir-Lambert Fund.

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by MIT News Office, Anne Trafton.