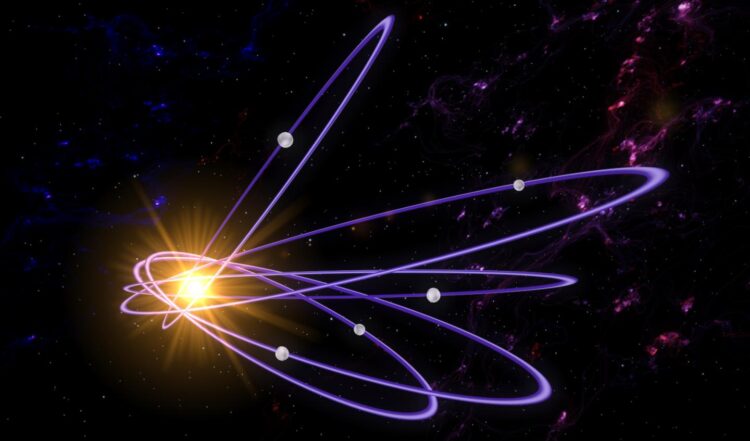

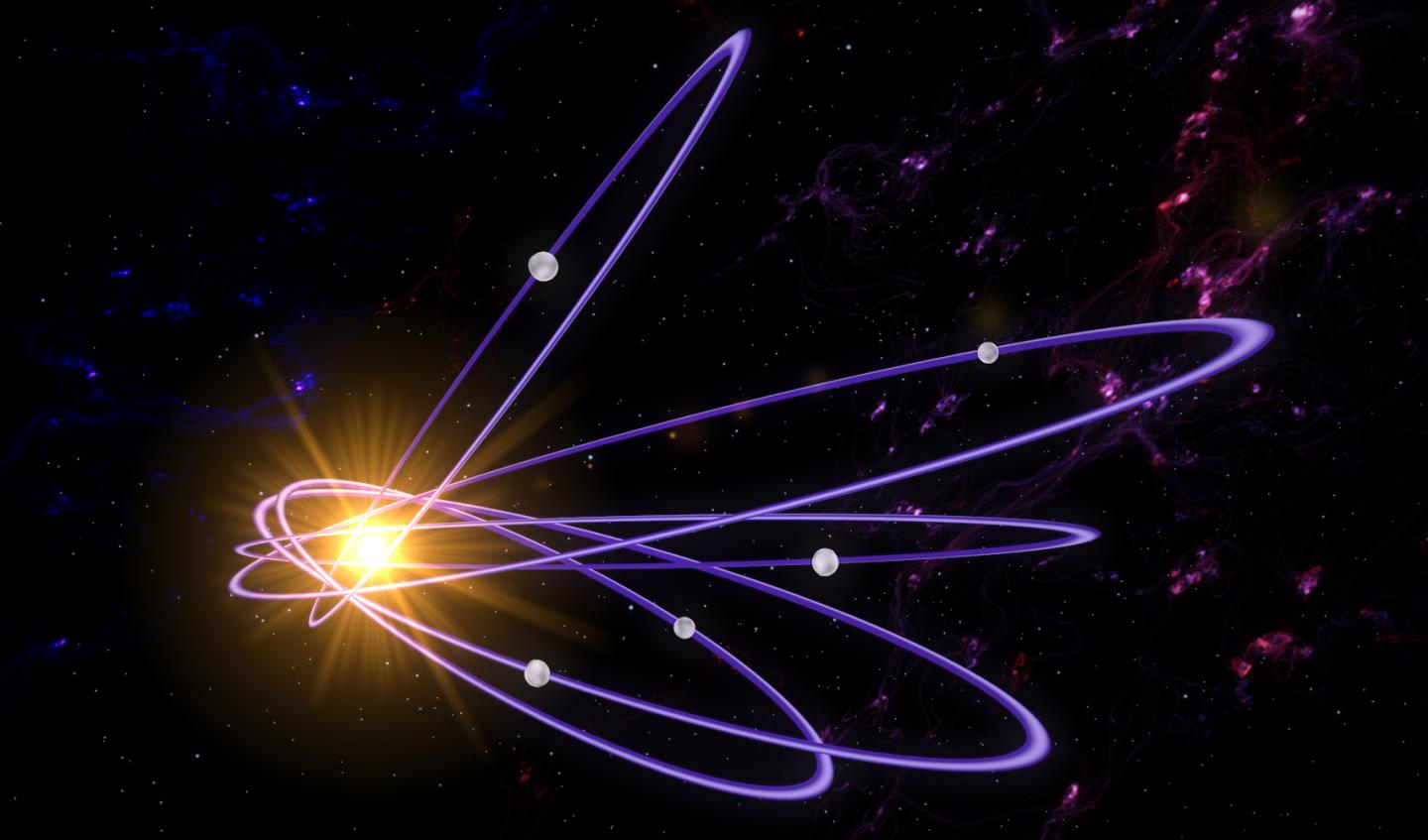

Credit: Credit: Steven Burrows/JILA

The outermost reaches of our solar system are a strange place–filled with dark and icy bodies with nicknames like Sedna, Biden and The Goblin, each of which span several hundred miles across.

Two new studies by researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder may help to solve one of the biggest mysteries about these far away worlds: why so many of them don’t circle the sun the way they should.

The orbits of these planetary oddities, which scientists call “detached objects,” tilt and buckle out of the plane of the solar system, among other unusual behaviors.

“This region of space, which is so much closer to us than stars in our galaxy and other things that we can observe just fine, is just so unknown to us,” said Ann-Marie Madigan, an assistant professor in the Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences (APS) at CU Boulder.

Some researchers have suggested that something big could be to blame–like an undiscovered planet, dubbed “Planet 9,” that scatters objects in its wake.

But Madigan and graduate student Alexander Zderic prefer to think smaller. Drawing on exhaustive computer simulations, the duo makes the case that these detached objects may have disrupted their own orbits–through tiny gravitational nudges that added up over millions of years.

The findings, Madigan said, provide a tantalizing hint to what may be going on in this mysterious region of space.

“We’re the first team to be able to reproduce everything, all the weird orbital anomalies that scientists have seen over the years,” said Madigan, also a fellow at JILA. “It’s crazy to think that there’s still so much we need to do.”

The team published its results July 2 in the Astronomical Journal and last month in the Astronomical Journal Letters.

Power to the asteroids

The problem with studying the outer solar system, Madigan added, is that it’s just so dark.

“Ordinarily, the only way to observe these objects is to have the sun’s rays smack off their surface and come back to our telescopes on Earth,” she said. “Because it’s so difficult to learn anything about it, there was this assumption that it was empty.”

She’s one of a growing number of scientists who argue that this region of space is far from empty–but that doesn’t make it any easier to understand.

Just look at the detached objects. While most bodies in the solar system tend to circle the sun in a flat disk, the orbits of these icy worlds can tilt like a seesaw. Many also tend to cluster in just one slice of the night sky, a bit similar to a compass that only points north.

Madigan and Zderic wanted to find out why. To do that, they turned to supercomputers to recreate, or model, the dynamics of the outer solar system in greater detail than ever before.

“We modeled something that may have once existed in the outer solar system and also added in the gravitational influence of the giant planets like Jupiter,” said Zderic, also of APS.

In the process, they discovered something unusual: the icy objects in their simulations started off orbiting the sun like normal. But then, over time, they began to pull and push on each other. As a result, their orbits grew wonkier until they eventually resembled the real thing. What was most remarkable was that they did it all on their own–the asteroids and minor planets didn’t need a big planet to throw them for a loop.

“Individually, all of the gravitational interactions between these small bodies are weak,” Madigan said. “But if you have enough of them, that becomes important.”

Earth times 20

Madigan and Zderic had seen hints of similar patterns in earlier research, but their latest results provide the most exhaustive evidence yet.

The findings also come with a big caveat. In order to make Madigan and Zderic’s theory of “collective gravity” work, the outer solar system once needed to contain a huge amount of stuff.

“You needed objects that added up to something on the order of 20 Earth masses,” Madigan said. “That’s theoretically possible, but it’s definitely going to be bumping up against people’s beliefs.”

One way or another, scientists should find out soon. A new telescope called the Vera C. Rubin Observatory is scheduled to come online in Chile in 2022 and will begin to shine a new light on this unknown stretch of space.

“A lot of the recent fascination with the outer solar system is related to technological advances,” Zderic said. “You really need the newest generation of telescopes to observe these bodies.”

###

Media Contact

Daniel Strain

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.