Researchers have long searched for a durable artificial heart that can work as efficiently as the one supplied by nature.

Now Carmat, a company based in Paris, has designed an artificial heart fashioned in part from cow tissue. The device, soon to be tested in patients with heart failure, is regulated by sensors, software and microelectronics. And its power will come from two external, wearable lithium-ion batteries.

Fifteen years in development, the heart has been approved for clinical trials at cardiac surgery centers in Belgium, Poland, Saudi Arabia and Slovenia, where staff members are receiving training and patients are being screened, said Dr. Piet Jansen, medical director at Carmat.

In France, where the device is not yet cleared for human implantation, regulators have requested more animal tests, Dr. Jansen said; those tests are continuing.

Artificial hearts aren’t new, of course, but the Carmat heart is unusual in its design, said Dr. Joseph Rogers, an associate professor at Duke University and medical director of its cardiac transplant and mechanical circulatory support program. Surfaces in the new heart that touch human blood are made from cow tissue instead of artificial materials like plastic that can cause problems like clotting.

“The way they’ve incorporated biological surfaces for any place that contacts blood is a really nice advantage,” Dr. Rogers said. “If they have this design right, this could be a game changer.” He added that it could lessen the need for anticoagulation medicines. (Dr. Rogers has no financial connections to Carmat.)

This is the first artificial heart to use cow-derived materials — specifically, tissue from the pericardial sac that surrounds the heart. Biological tissue has been used in earlier mechanical blood pumps only in valves, Dr. Rogers said.

Thousands of people in the United States need a replacement heart, said Dr. Lynne Warner Stevenson, a professor at Harvard Medical School and director of the cardiomyopathy and heart-failure program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “It’s estimated that if we had enough donor hearts to go around, 100,000 to 150,000 people in the United States with heart failure would benefit,” she said. “Transplants work best, but we have only 2,000 or so adult hearts” that are available each year, she said. “It’s a huge problem.”

There are long-established options for patients while they await transplants, Dr. Stevenson said, including installing an artificial heart made by SynCardia until a donor heart is available.

When the natural heart is partly damaged or diseased, patients might keep it and have a mechanical aid implanted to bolster blood flow. Such pumps — especially those that aid the left side of the heart — are in wide use both as a bridge to a transplant and for lifetime therapy.

A totally artificial heart for extended use would be of great value, but it’s far too early to know if the Carmat heart, as yet untried in humans, will be that device. “The whole history of mechanical devices is that people thought they had devices where blood wouldn’t clot. But they didn’t,” Dr. Stevenson said.

Dr. Jansen said that the cost of the Carmat heart would be about $200,000 and that he did not expect it to be brought to market in Europe before the end of 2014. Once the company gains momentum with its European clinical studies, he said, it plans to start working through the regulatory process in the United States.

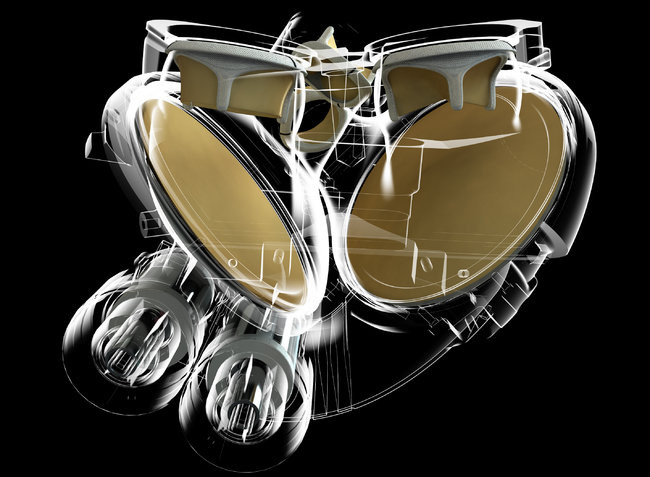

The Carmat heart has two chambers, each divided by a membrane. That membrane has cow tissue on one side — the side that is in contact with blood — and polyurethane on the other side, which touches the miniaturized pumping system of motors and hydraulic fluids that changes the membrane’s shape. (The motion of the membrane pushes the blood out to the body.) The embedded electronics and software adjust the rate of blood flow. Patients can wear the batteries under the arm in a holster, or in a belt, among other options.

Cow tissue is also used for the heart’s artificial valves, which were created by Dr. Alain Carpentier, a cardiac surgeon and a pioneer of heart valve repair who is also a co-founder of Carmat and its scientific director. Such valves have been used in heart-valve replacement surgery for decades. The cow tissue is chemically treated so that it is sterile and biologically inert.

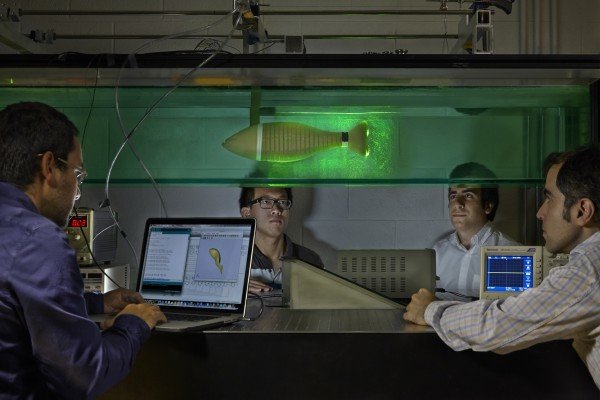

The heart’s design and development relied heavily on aerospace testing strategies by EADS, the European Aeronautic Defense and Space Company, one of Carmat’s backers, Dr. Jansen said. Even so, duplicating the durability of a human heart will not be easy, said Dr. Robert Kormos, director of the artificial heart program at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and co-director of its heart transplant program.

“We can test these pumps on the bench in the laboratory, and in animals, but there is no true long-term data until you implant them in people for trials,” he said.

DR. JANSEN said that one design requirement for the heart was that it last five years. The company has been doing bench tests to see whether the new heart will stand up to that level of wear and tear. “Whether it lasts five years in the patient we will have to prove clinically,” he said.

Dr. Stevenson of Harvard is optimistic about the new device.

“Innovation is what we need,” she said. “This new device is exciting. I applaud the pioneers who developed it, and the patients and families who will go down this path for the first time.”

A version of this article appeared in print on July 14, 2013, on page BU3 of the New York edition with the headline: The Artificial Heart Is Getting a Bovine Boost.

Story Source:

The above story is reprinted from materials provided by The New York Times, ANNE EISENBERG.