High school students in a Stanford bioengineering boot camp tackled real-world projects, such as using sensors to ensure that surgeons don’t accidentally leave pieces of gauze inside their patients. The camp was organized by a Stanford undergrad, Stephanie Young, who brought in expert help.

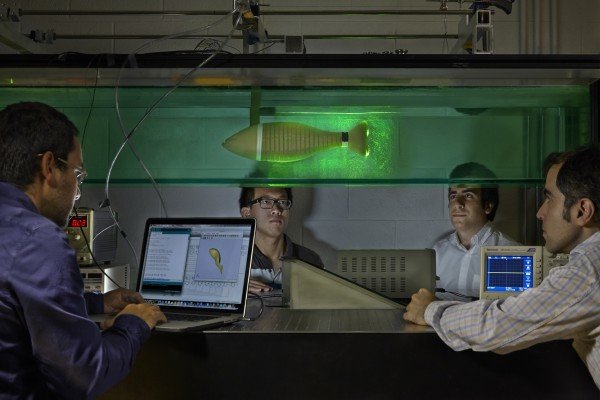

Flanked by three teammates, 17-year-old Alex Lee bent over a worktable in the Product Realization Lab at Stanford to show how he and his fellow high school students had embedded a sensor into a strip of surgical gauze.

Demonstrating the device, Lee waved his smart phone over the “smart gauze” and elicited a beep – showing how the sensor in the gauze and detector in the phone worked together to enable surgical staff to locate non-metallic objects that could, if left behind, harm patients and prompt lawsuits.

“Surgical sponges are the most common item left behind in surgeries and they’re very difficult to detect,” said Lee, who was one of 26 participants in a free, six-week bioengineering boot camp for high school students organized by Stanford undergraduate Stephanie Young.

Young, a bioengineering student who grew up in San Mateo, Calif., said she got the idea for the boot camp last year after talking with a friend who had gone through a similar intensive summer program in the law.

“I wondered why we didn’t have one of those for bioengineering,” she said.

The idea simmered all year until the spring, when Young won the support of Norbert Pelc, chairman of the Department of Bioengineering.

“This is a discipline for the future and priming the pipeline with students is something we need to do,” said Pelc, whose personal involvement in the boot camp allowed him to observe the high school attendees first-hand. “They’re fearless,” he said.

Young ran the program with help from her sister, Jacqueline Young, and Ken Xiong, ’13, who received a bachelor’s degree from the School of Engineering.

The program participants, who all attend Silicon Valley high schools, were nominated by their teachers or advisers. The boot camp consisted of six day-long sessions divided between classroom instruction and problem-solving exercises. Bioengineering department faculty served as guest lectures. Stanford graduate and undergraduate students mentored the high school teams.

“We were teaching them the same concepts we teach undergraduates and graduates,” Young said. “They already had such high levels of knowledge. It was beyond anything we expected.”

Young said the boot camp employed the learning-by-building approach honed by Stanford’s Product Realization Lab, a teaching environment that offers design and prototyping facilities in support of student product creation. The high school students were presented with a series of real-world challenges and grouped into teams to devise solutions, which they then fashioned in the lab.

“We wanted them to come up not only with an idea but a rough prototype,” Xiong said.

The notion of embedding sensors into gauze arose when Lee and his teammates took on the challenge of finding a way to ensure that surgical tools aren’t left in patients. They focused on cotton gauze surgical sponges because they are more difficult to detect than metal fragments, which could be spotted by x-ray, for instance.

As the team brainstormed, Lee thought of using near field communication (NFC), the same technology that enables smart phones to swap information, wirelessly, over short distances. NFC systems shoot a radio beam against a passive target or tag. Team member Justine Sun, 17, said their research suggested that NFC tags could be produced cheaply and sewn into surgical gauze. Sixteen-year-old Supriya Sanjay explained how the team devised a way to sterilize these electronic parts without destroying them during the manufacturing process.

“The sensor is programmable,” said team member Zoe Nuyens, an 18-year-old Menlo-Atherton High School graduate, explaining how this would allow surgical staff to number every piece of gauze and then account for each item after the operation.

Other teams took on similar challenges: finding an easier way to diagnose sleep apnea; designing a new drug delivery technology; reducing the wear-and-tear on knee and hip replacements to reduce the need for replacement surgery.

Becky DiMarco, a doctoral candidate in bioengineering, mentored five high school students, ages 15 to 18, who took on the wear-and-tear challenge. Watching them fashion their prototype in the Product Realization Lab, DiMarco said the students independently came up with several realistic possibilities based on their studies of the scientific literature. Their suggested fixes included achieving a better bond between the bone and the implant by layering in a synthetic form of the protein fibronectin, whose functions include promoting cell adhesion.

“That’s one of the same things we’re working on in our lab,” said DiMarco, adding, “They are way ahead of where I was at that age.”

The boot camp will culminate on Wednesday, Aug. 7, when each team of students will present its findings at a demonstration to be held from 2 to 5 p.m. in room 101 in the Li Ka Shing Center for Learning and Knowledge in the Stanford Medical Center complex. The demonstration is open to the public.

Reflecting on what he has seen this summer, Pelc said he was struck by how the high school students approached their assignments uninhibited by conventional notions of what was or wasn’t possible.

“Sometimes they will run at full speed into a brick wall,” he said, and then paused before adding, “but sometimes they may break through.”

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by Stanford University, Tom Abate, School of Engineering, 650-736-2245, [email protected].