PHILADELPHIA – Evidence of DNA "scrunching" may one day lead to a new class of drugs against viruses, according to a research team from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, the Georgia Institute of Technology, and Columbia University. The team is led by Stephen C. Harvey, PhD, an adjunct professor in the department of Biochemistry and Biophysics at Penn. The scientists report in The Journal of Physical Chemistry B that DNA may go through a repetitive cycle of contraction and elongation, or as they put it, "scrunching," to generate the forces required to drive the DNA into a virus during replication. A better understanding of viral reproduction could be the basis of new ways to fight infectious pathogens.

During replication, viruses take over the host cell machinery to make copies of their genetic material and build protein shells called capsids to contain their genomic DNA or RNA. In some DNA viruses, such as herpesviruses, the empty capsid forms first, and the DNA is then packaged by a protein "motor" on the capsid.

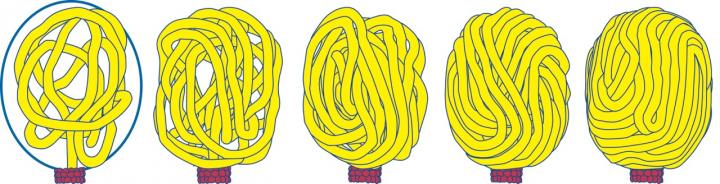

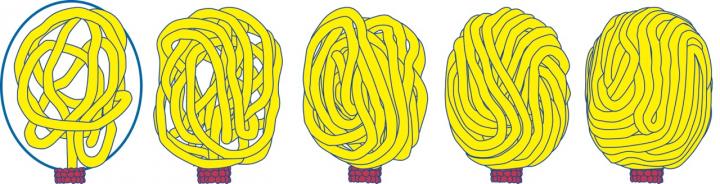

In 2015, Harvey proposed that the traditional model in which the proteins push the DNA forward with a series of lever-like motions might be wrong. He suggested that the proteins might generate a cycle of DNA dehydration and rehydration. DNA is known to shorten by about 25 percent when it is dehydrated. He proposed that the resulting cycle of shortening and lengthening motions could be coupled to a DNA-protein grip-release cycle to generate forward motion. He called this the "scrunchworm model."

"For some time now, we have been contemplating how viral DNA gets into the capsid so that one day we can block this step as a way to halt infection," Harvey said. They tested the scrunchworm model in a series of computer simulations. The structures of the herpesviruses are not known with sufficient resolution to permit this kind of modeling, so the team examined DNA packaging in phi29, a DNA virus of similar structure that infects bacteria. They examined the interaction of DNA with the phi29 connector proteins, which form half of the protein motor. The DNA spontaneously underwent scrunching motions, without being pushed or pulled by protein levers. This provides the first support for the scrunchworm model.

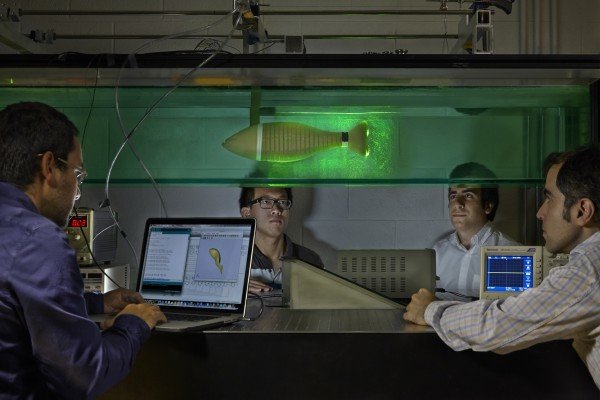

It is essential to test the scrunchworm model experimentally, and Harvey has formed a collaboration with two other research groups to test predictions made by the scrunchworm model. These involve grabbing a single viral particle with a pair of "laser tweezers" and pulling on the DNA tail as the DNA is packaged. The model predicts that DNAs with different sequences will generate different amounts of force, and that DNA with RNA inserts cannot be packaged.

"Even if these experiments disprove the scrunchworm model, they will provide information that will help us figure out how these motors work," Harvey said. "The purpose of modeling is to drive experiments and simulations that advance our understanding, regardless how they turn out."

###

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM070785) and the National Science Foundation.

Penn Medicine is one of the world's leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (founded in 1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which together form a $5.3 billion enterprise.

The Perelman School of Medicine has been ranked among the top five medical schools in the United States for the past 18 years, according to U.S. News & World Report's survey of research-oriented medical schools. The School is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $373 million awarded in the 2015 fiscal year.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System's patient care facilities include: The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania and Penn Presbyterian Medical Center — which are recognized as one of the nation's top "Honor Roll" hospitals by U.S. News & World Report — Chester County Hospital; Lancaster General Health; Penn Wissahickon Hospice; and Pennsylvania Hospital — the nation's first hospital, founded in 1751. Additional affiliated inpatient care facilities and services throughout the Philadelphia region include Chestnut Hill Hospital and Good Shepherd Penn Partners, a partnership between Good Shepherd Rehabilitation Network and Penn Medicine.

Penn Medicine is committed to improving lives and health through a variety of community-based programs and activities. In fiscal year 2015, Penn Medicine provided $253.3 million to benefit our community.

Media Contact

Karen Kreeger

[email protected]

215-349-5658

@PennMedNews

http://www.uphs.upenn.edu/news/

The post New antiviral drugs could come from DNA ‘scrunching’ appeared first on Scienmag.