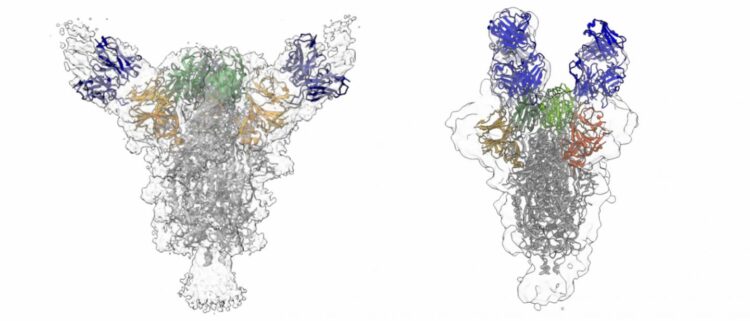

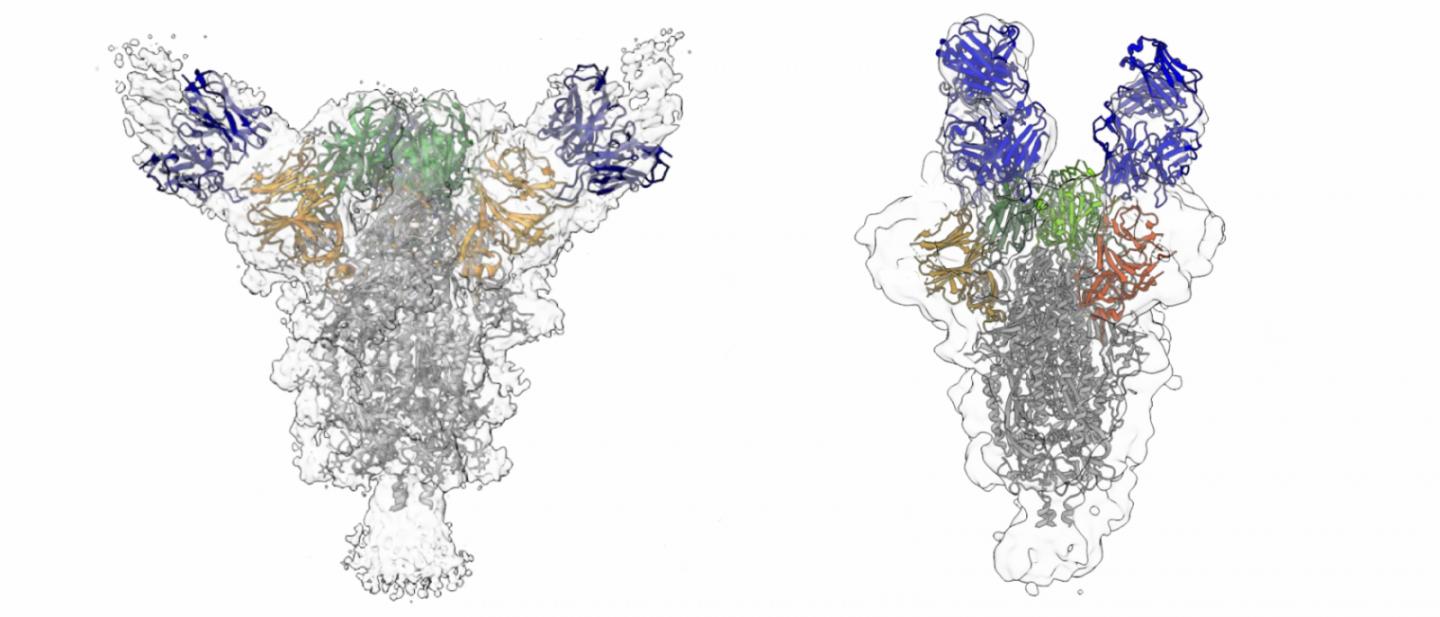

Credit: David Ho / Columbia University Irving Medical Center

Researchers at Columbia University Irving Medical Center have isolated antibodies from several COVID-19 patients that, to date, are among the most potent in neutralizing the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

These antibodies could be produced in large quantities by pharmaceutical companies to treat patients, especially early in the course of infection, and to prevent infection, particularly in the elderly.

“We now have a collection of antibodies that’s more potent and diverse compared to other antibodies that have been found so far, and they are ready to be developed into treatments,” says David Ho, MD, scientific director of the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center and professor of medicine at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, who directed the work.

The researchers have confirmed that their purified, strongly neutralizing antibodies provide significant protection from SARS-CoV-2 infection in hamsters, and they are planning further studies in other animals and people.

The findings were published today in the journal Nature.

Why look for neutralizing antibodies

One of the human body’s major responses to an infection is to produce antibodies–proteins that bind to the invading pathogen to neutralize it and mark it for destruction by cells of the immune system.

Though a number of drugs and vaccines in development for COVID-19 are in clinical trials, they may not be ready for several months. In the interim, SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies produced by COVID-19 patients could be used to treat other patients or even prevent infection in people exposed to the virus. The development and approval of antibodies for use as a treatment usually takes less time than conventional drugs.

This approach is similar to the use of convalescent serum from COVID-19 patients, but potentially more effective. Convalescent serum contains a variety of antibodies, but because each patient has a different immune response, the antibody-rich plasma used to treat one patient may be vastly different from the plasma given to another, with varying concentrations and strengths of neutralizing antibodies.

Sicker patients produce more potent antibodies

When SARS-CoV-2 arrived and led to a pandemic at the beginning of the year, Ho rapidly shifted the focus of his HIV/AIDS laboratory to work on the new virus. “Most of my team members pretty much have been working nonstop 24/7 since early March,” says Ho.

The researchers had easy access to blood samples from patients with moderate and severe disease who were treated at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York City, the epicenter of the pandemic earlier this year. “There was plenty of clinical material, and that allowed us to select the best cases from which to isolate these antibodies,” Ho says.

Ho’s team found that although many patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 produce significant quantities of antibodies, the quality of those antibodies varies. In the patients they studied, those with severe disease requiring mechanical ventilation produced the most potently neutralizing antibodies.

“We think that the sicker patients saw more virus and for a longer period of time, which allowed their immune system to mount a more robust response,” Ho says. “This is similar to what we have learned from the HIV experience.”

Antibody cocktails

The majority of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies bind to the spike glycoprotein–a feature that gives the virus its corona–on the virus’s surface. Some of the most potent antibodies were directed to the receptor binding domain (where the virus attaches to human cells), but others were directed to the N-terminal region of the spike protein.

The Columbia team found a more diverse variety of antibodies than previous efforts, including new, unique antibodies that were not reported earlier.

“These findings show which sites on the viral spike are most vulnerable,” Ho says. “Using a cocktail of different antibodies that are directed to different sites in spike will help prevent the virus becoming resistant to the treatment.”

Implications for vaccines

“We discovered that these powerful antibodies are not too difficult for the immune system to generate. This bodes well for vaccine development,” Ho says. “Vaccines that elicit strong neutralizing antibodies should provide robust protection against the virus.”

Antibodies may also be useful even after a vaccine is available. For example, a vaccine may not work well in the elderly, in which case the antibodies could play a key role in protection.

Implications for immunity

This research demonstrates that people with severe disease are more likely to have a durable antibody response, however more research needs to be done to answer the critical question about how long immunity to COVID-19 will last.

What’s next

The researchers are now designing experiments to test the strategy in other animals, and eventually in humans.

If the animal results hold true in humans, the pure, highly neutralizing antibodies could be given to patients with COVID-19 to help them clear the virus.

Caveats

Although tremendously informative for researchers developing vaccines and antiviral therapies, the findings are early-stage preclinical results and the antibodies are not yet ready for use in people.

###

David Ho is the Clyde ’56 and Helen Wu Professor of Medicine at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons and scientific director and chief executive officer of the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center.

The new paper appears in the journal Nature.

This study was supported by grants from the Jack Ma Foundation, the JPB Foundation, the NIH (U24 GM129539), the Simons Foundation (SF349247), and the New York State Assembly.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Media Contact

Lucky Tran

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/