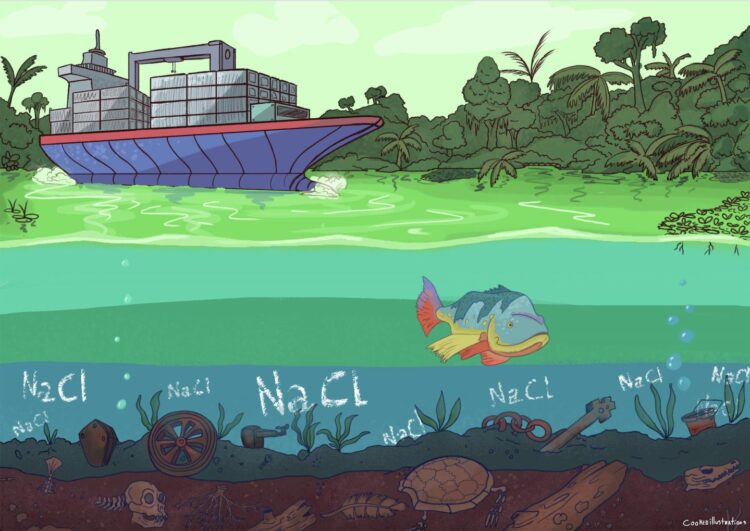

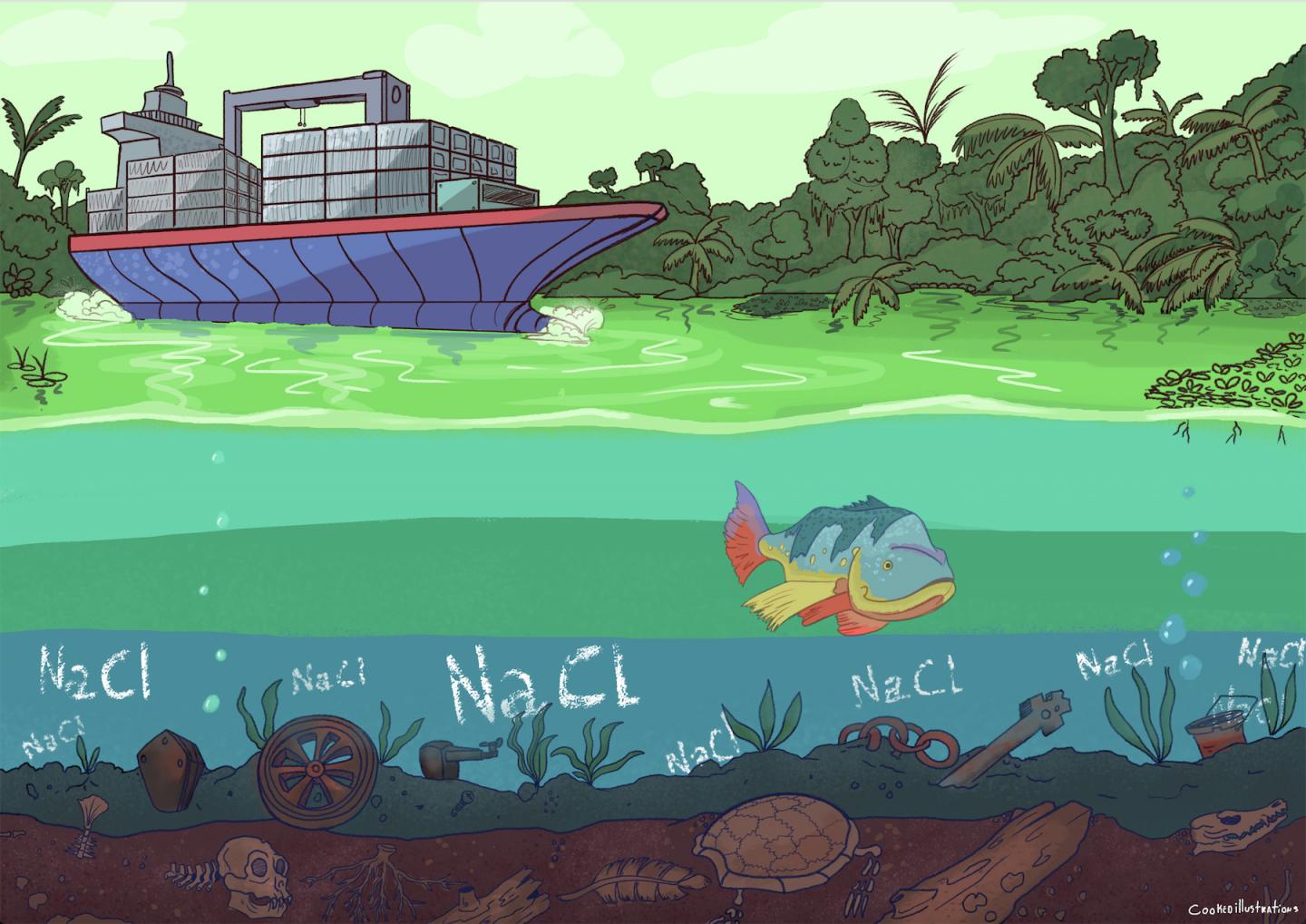

Credit: Ian Cooke/Cooked Illustrations

Humans have manipulated and managed rivers with dams for millennia. The number of river dam projects is predicted to rise sharply in the future, especially in the tropics where demand for hydroelectricity and water is accelerating. What are the long-term impacts of dams on highly biodiverse tropical forests? Scientists at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) and collaborating institutions turned to one of the oldest tropical dams in the world to answer this question: The Panama Canal.

Over a century ago, the Chagres River was dammed to form Gatun Lake, the principal waterway of the canal and at the time the largest man-made lake in the world. Jorge Salgado, STRI fellow and postdoctoral researcher at the University of Nottingham, led a team that retrieved sediment cores from a basin in the lake and, with paleoecological techniques and historical records from the Panama Canal Authority, built a chronological sequence of biological and environmental changes. Their findings were recently published in the journal Science of the Total Environment.

“The unique historical data available from the Panama Canal makes it one of a kind,” Salgado said. “When combined with paleoecological data, we have an unrivalled opportunity to explore the impacts of damming on a tropical river over a period of more than 100 years.”

The data reveal the narrative of biological and environmental events that took place in Lake Gatun, ranging from enhanced pollution caused by canal construction, regional climate changes and shifts in land-use to the introduction of invasive species and salt-water intrusions.

“In most cases, the local impacts of dams would begin to dominate, but we found that in the Panama Canal, natural river processes continue to be very important today,” Salgado said.

The researchers’ findings emphasize the need to understand both long-term drivers of natural change, such as precipitation and river flow dynamics, and the human-driven changes that affect water bodies in order to effectively manage and preserve the lake basin’s ecological functioning.

“Coring lake sediments gives us the chance to travel back in time and chronicle ecosystem change,” said Aaron O’Dea, STRI staff scientist and co-author of the study. “It’s a really powerful way to uncover past events and reveal ecological and environmental processes that would otherwise be undetectable. This is especially important in highly biodiverse tropical ecosystems where long-term monitoring data may be limited.”

Salgado has plans to continue time-traveling. He and his team will collect more cores and reconstruct historical changes in other areas of the Panama Canal.

“Since its construction, the Panama Canal has protected a wide-swathe of biodiverse lowland tropical terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems,” Salgado said. “Reconstructing the past can help us predict the future responses of both protected and non-protected areas to further global and local changes. This is paramount to the biological health of the canal.”

###

Members of the research team are affiliated with the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI), Universidad de Los Andes, University of Regina, University College London, Universidad Católica de Colombia and University of Bologna. Researchers involved were funded by STRI, the Inter-American Institute for Global Change Research, the US National Science Foundation, Universidad de Los Andes, Universidad Católica de Colombia and the Ministerio de Ciencias, Tecnología e Innovación (MINCIENCIAS).

The Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, headquartered in Panama City, Panama, is a unit of the Smithsonian Institution. The institute furthers the understanding of tropical biodiversity and its importance to human welfare, trains students to conduct research in the tropics and promotes conservation by increasing public awareness of the beauty and importance of tropical ecosystems.

Media Contact

Leila Nilipour

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.