Overheated mice do not defend against flu in lab study

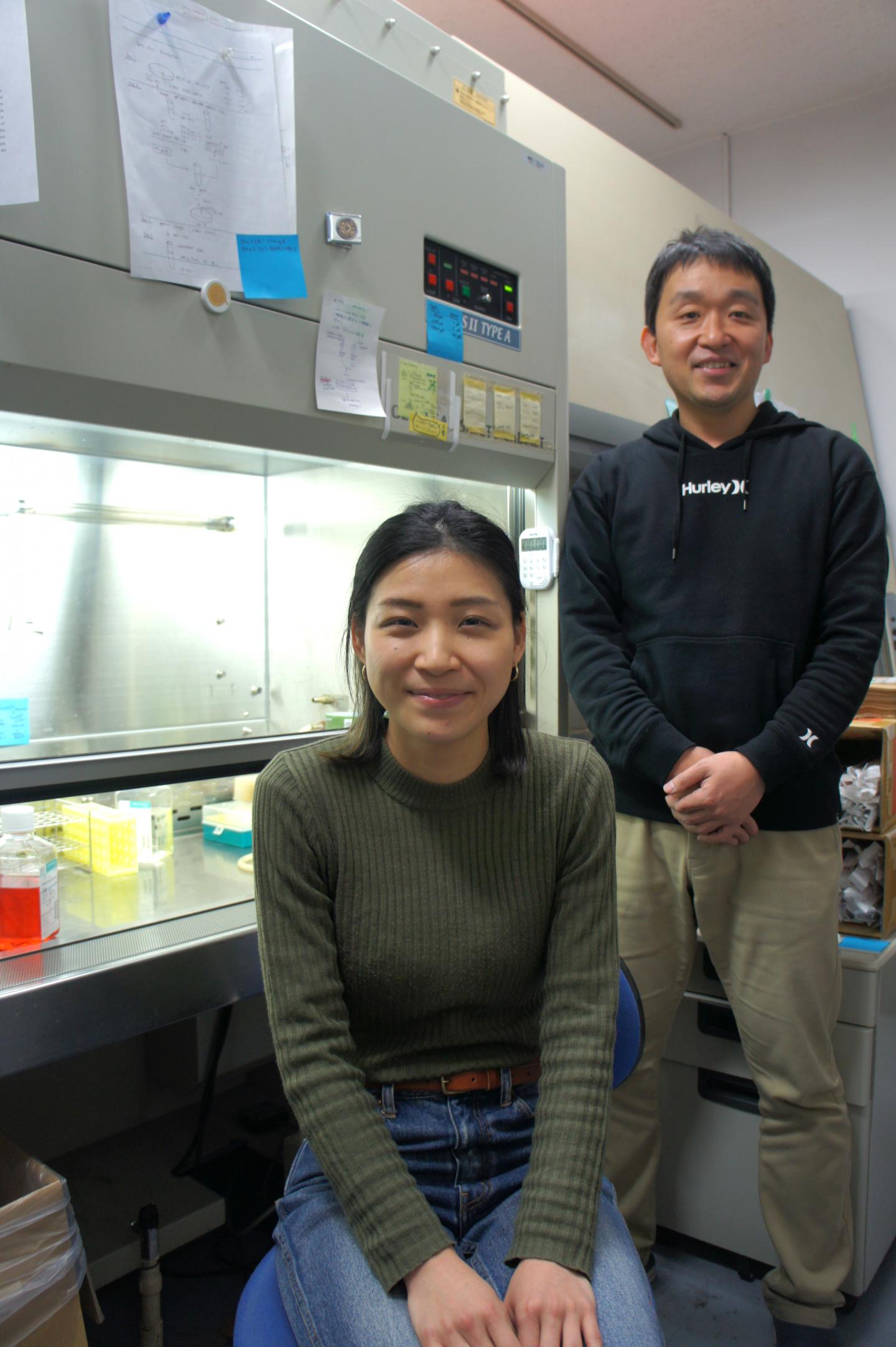

Credit: University of Tokyo CC-BY

Heat waves can reduce the body’s immune response to flu, according to new research in mice at the University of Tokyo. The results have implications for how climate change may affect the future of vaccinations and nutrition.

Climate change is predicted to reduce crop yields and nutritional value, as well as widen the ranges of disease-spreading insects. However, the effects of heat waves on immunity to influenza had not been studied before.

University of Tokyo Associate Professor Takeshi Ichinohe and third-year doctoral student Miyu Moriyama investigated how high temperatures affect mice infected with influenza virus.

Flu in a heat wave

“Flu is a winter-season disease. I think this is why no one else has studied how high temperatures affect flu,” said Ichinohe.

The influenza virus survives better in dry, cold air, so it usually infects more people in winter. However, Ichinohe is interested in how the body responds after infection.

The researchers housed healthy, young adult female mice at either refrigerator-cold temperature (4 degrees Celsius or 39.2 degrees Fahrenheit), room temperature (22 C or 71.6 F), or heat wave temperature (36 C or 96.8 F).

When infected with flu, the immune systems of mice in hot rooms did not respond effectively. Most affected by the high heat condition was a critical step between the immune system recognizing influenza virus and mounting a specific, adaptive response.

Otherwise, heat-exposed mice had no other significant changes to their immune system: They had normal reactions to flu vaccines injected under the skin. Moreover, bacteria living in the gut, which are increasingly becoming regarded as important for health, remained normal in the mice living in hot rooms.

Temperature and nutrition

Notably, mice exposed to high temperature ate less and lost 10 percent of their body weight within 24 hours of moving to the hot rooms. Their weight stabilized by day two and then mice were infected by breathing in live flu virus on their eighth day of exposure to heat.

Mice living in heat wave temperatures could mount a normal immune response if researchers provided supplemental nutrition before and after infection. Researchers gave mice either glucose (sugar) or short-chain fatty acids, chemicals naturally produced by intestinal bacteria.

In experiments at room temperature, researchers surgically connected mice so that body fluids moved freely between underfed and normally fed mice, both infected with influenza. The fluids from normally fed mice prompted the immune systems of underfed mice to respond normally to the flu virus.

“Does the immune system not respond to influenza virus maybe because the heat changes gene expression? Or maybe because the mice don’t have enough nutrients? We need to do more experiments to understand these details,” said Moriyama.

The results may shed light on the unfortunate experience of getting sick again while recovering from another illness.

“People often lose their appetite when they feel sick. If someone stops eating long enough to develop a nutritional deficit, that may weaken the immune system and increase the likelihood of getting sick again,” said Ichinohe.

Future of infection

An important area of future study will be the effect of high temperature on different types of vaccinations. Flu vaccines injected into the upper arm use inactivated virus, but vaccines sprayed into the nose use live attenuated (weakened) virus.

“The route of delivery and the type of virus both may change how the immune system responds in high temperatures,” said Moriyama.

Until more research can clarify what these findings may mean for humans, Ichinohe and Moriyama cautiously recommend a proactive approach to public health.

“Perhaps vaccines and nutritional supplements could be given simultaneously to communities in food-insecure areas. Clinical management of emerging infectious diseases, including influenza, Zika, and Ebola, may require nutritional supplements in addition to standard antiviral therapies,” said Ichinohe.

The researchers are planning future projects to better understand the effects of temperature and nutrition on the immune system, including experiments with obese mice, chemical inhibitors of cell death, and different humidity levels.

###

About the research

The strain of flu used in this research was A/PR8/34 influenza virus, a type of H1N1 flu originally isolated in Puerto Rico in 1934 and now common in laboratory mouse studies.

(https:/

This research is a peer-reviewed experimental study with mice published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

Journal Article

Moriyama M and T Ichinohe. 2019. High ambient temperature dampens adaptive immune responses to influenza A virus infection. PNAS. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1815029116

Related Links

Institute of Medical Science: http://www.

Ichinohe Laboratory website: http://www.

Lab Facebook page (Japanese): @Ichinohe.Lab https:/

Research Contact

Associate Professor Takeshi ICHINOHE

The Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo, 4-6-1 Shirokanedai, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108-8639, JAPAN

Tel: +81-(0)3-6409-2125

Email: [email protected]

Press Contacts

Ms. Caitlin Devor

Division for Strategic Public Relations, The University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8654, JAPAN

Tel: +81-(0)3-5841-0876

Email: [email protected]

Ms. Noriko Matsumoto

The Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo, 4-6-1 Shirokanedai, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108-8639, JAPAN

Tel: +81-(0)3-5841-2018

Email: [email protected]

About the University of Tokyo

The University of Tokyo is Japan’s leading university and one of the world’s top research universities. The vast research output of some 6,000 researchers is published in the world’s top journals across the arts and sciences. Our vibrant student body of around 15,000 undergraduate and 15,000 graduate students includes over 2,000 international students. Find out more at http://www.

Media Contact

Takeshi Ichinohe

[email protected]

81-036-409-2125

Related Journal Article

http://dx.