Investigators at the Medical University of South Carolina report in Microbiome that autoantibody production in HIV-positive patients who have undergone antiretroviral therapy is linked to levels of Staphylococcus products in their blood.

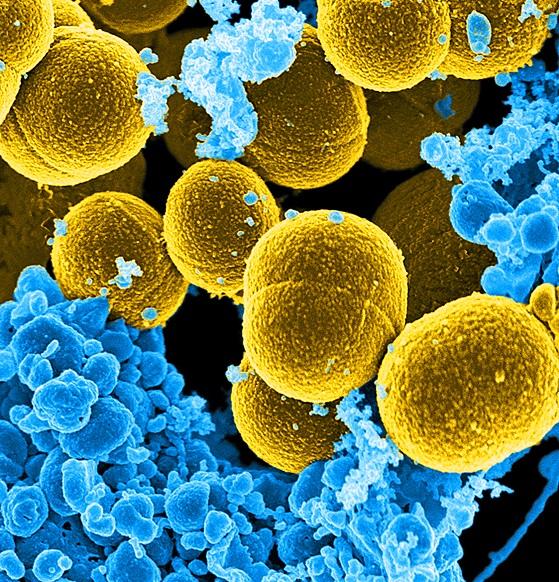

Credit: Frank DeLeo, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)

Human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, attacks the immune system, making affected individuals more susceptible to infections. When patients with HIV are treated with antiretroviral therapy (ART), their immune system can recover, but some of them produce self-destructive proteins, or autoantibodies.

Instead of attacking foreign invaders such as bacteria or viruses, some autoantibodies attack the body’s own cells. This is known as autoimmunity. We all produce low levels of autoantibodies. However, when they are produced persistently at high levels, autoimmunity may occur.

In an article in Microbiome, Wei Jiang, M.D., associate professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), and her team report that HIV-positive, ART-treated patients with high levels of autoantibodies also have increased levels of bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus) products in their blood.

The MUSC study compared autoantibody production in HIV-positive patients and healthy individuals before and after receiving a seasonal flu vaccine. Patients provided blood samples before vaccination and one and two weeks after. The blood samples were tested using a 125-autoantibody array panel.

The autoimmune response in the HIV-positive patients was linked to the presence of Staphylococcus aureus products in the blood. This is the same bacteria responsible for skin staph infections. Some HIV-positive patients have a higher baseline level of these bacterial products in their system. The team examined other strains of bacteria but linked only Staphylococcus aureus to autoantibody production in HIV-positive individuals.

A “leaky gut” could explain the increased level of Staphylococcus products in the blood of HIV-positive patients.

In patients with “leaky gut,” the intestinal lining is weakened, enabling bacteria and toxic products in the gut to enter the bloodstream, where they become vulnerable to the immune system. The immune system’s attacks on these bacteria could also injure the body’s own tissues.

A “leaky gut” is associated with persistent inflammation and several chronic illnesses, including HIV, irritable bowel syndrome, celiac disease, and type 1 diabetes.

To verify their findings, Jiang and her team injected heat-killed Staphylococcus bacteria into healthy mice and found that they did in fact stimulate autoantibody production.

“We used animals to verify what we found in humans,” explains Jiang. “We saw that the level of Staphylococcus product was correlated with autoantibody production in HIV patients, and we hypothesized that these bacteria induced autoantibodies, so we tested our hypothesis in mice.”

The mouse studies were supported by voucher funding from the South Carolina Clinical & Translational Research (SCTR) Institute, an NIH-funded Clinical and Translational Science Awards hub at MUSC.

The ability to further explore clinical findings in an animal model was crucial to this study. The mouse study showed that injection of Staphylococcus bacteria stimulates autoantibody production.

“We are now studying which Staphylococcus products are active in autoantibody production in mice,” says Jiang. “It may be possible to design an inhibitor to block these bacteria from activating the immune cells.”

Going forward, Jiang and her team hope to design a drug that inhibits Staphylococcus to help prevent autoimmunity in HIV-positive patients receiving ART.

###

About MUSC

Founded in 1824 in Charleston, The Medical University of South Carolina is the oldest medical school in the South. Today, MUSC continues the tradition of excellence in education, research, and patient care. MUSC educates and trains more than 3,000 students and residents, and has nearly 13,000 employees, including approximately 1,500 faculty members. As the largest non-federal employer in Charleston, the university and its affiliates have collective annual budgets in excess of $2.2 billion. MUSC operates a 700-bed medical center, which includes a nationally recognized Children’s Hospital, the Ashley River Tower (cardiovascular, digestive disease, and surgical oncology), Hollings Cancer Center (a National Cancer Institute-designated center) Level I Trauma Center, and Institute of Psychiatry. For more information on academic programs or clinical services, visit musc.edu. For more information on hospital patient services, visit muschealth.org.

About SCTR

The South Carolina Clinical & Translational Research (SCTR) Institute, a National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Science Awards hub, is the catalyst for changing the culture of biomedical research, facilitating sharing of resources and expertise, and streamlining research-related processes to bring about large-scale, change in the clinical and translational research efforts in South Carolina. Our vision is to improve health outcomes and quality of life for the population through discoveries translated into evidence-based practice.

Media Contact

Heather Woolwine

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.