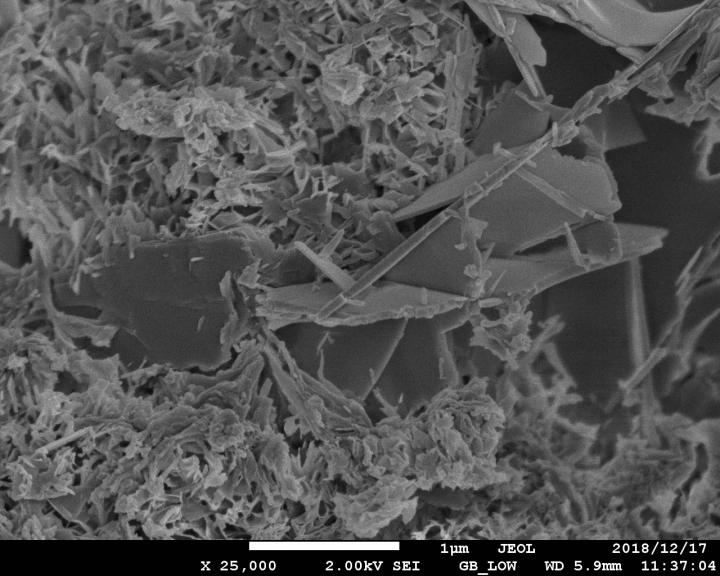

Credit: Ippei Maruyama, Nagoya University, and Chubu Electric Power Co.

A rare mineral that has allowed Roman concrete marine barriers to survive for more than 2,000 years has been found in the thick concrete walls of a decommissioned nuclear power plant in Japan. The formation of aluminous tobermorite increased the strength of the walls more than three times their design strength, Nagoya University researchers and colleagues report in the journal Materials and Design. The finding could help scientists develop stronger and more eco-friendly concrete.

“We found that cement hydrates and rock-forming minerals reacted in a way similar to what happens in Roman concrete, significantly increasing the strength of the nuclear plant walls,” says Nagoya University environmental engineer Ippei Maruyama.

Research has shown that Roman concrete used in the construction of marine barriers has managed to survive for more than two millennia because seawater dissolves volcanic ash in the mixture, leading to the formation of aluminous tobermorite. Since aluminous tobermorite is a crystal, it makes the concrete more chemically stable and stronger. It is very difficult to incorporate aluminous tobermorite directly into modern-day concrete. Scientists have generated the mineral in the lab, but it requires very high temperatures above 70°C. On the other hand, laboratory experiments have shown that hot environments are detrimental to concrete strength, which has led to regulations that limit its use to temperatures below 65°C.

Maruyama and his colleagues found that aluminous tobermorite formed in a nuclear reactor’s concrete walls when temperatures of 40-55°C were maintained for 16.5 years.

The samples were taken from the Hamaoka Nuclear Power Plant in Japan, which operated from 1976 to 2009.

In-depth analyses showed that the reactor’s very thick walls were able to retain moisture. Minerals used to make the concrete reacted in the presence of this water, increasing availability of silicon and aluminium ions and the alkali content of the wall. This ultimately led to the formation of aluminous tobermorite.

“Our understanding of concrete is based on short-term experiments conducted at lab time scales,” says Maruyama. “But real concrete structures give us more insights for long-term use.”

Maruyama and his colleagues are searching for ways to make concrete more durable and environmentally friendly. Cement used in concrete manufacturing produces nearly 10% of human-made carbon dioxide emissions, so the team is looking to produce more eco-friendly mixtures that still meet standardized requirements for strong concrete structures.

###

The study, “Long-term use of modern Portland cement concrete: The impact

of Al-tobermorite formation,” was published online in the journal Materials & Design on November 5, 2020 at DOI: 10.1016/j.matdes.2020.109297.

About Nagoya University, Japan

Nagoya University has a history of about 150 years, with its roots in a temporary medical school and hospital established in 1871, and was formally instituted as the last Imperial University of Japan in 1939. Although modest in size compared to the largest universities in Japan, Nagoya University has been pursuing excellence since its founding. Six of the 18 Japanese Nobel Prize-winners since 2000 did all or part of their Nobel Prize-winning work at Nagoya University: four in Physics – Toshihide Maskawa and Makoto Kobayashi in 2008, and Isamu Akasaki and Hiroshi Amano in 2014; and two in Chemistry – Ryoji Noyori in 2001 and Osamu Shimomura in 2008. In mathematics, Shigefumi Mori did his Fields Medal-winning work at the University. A number of other important discoveries have also been made at the University, including the Okazaki DNA Fragments by Reiji and Tsuneko Okazaki in the 1960s; and depletion forces by Sho Asakura and Fumio Oosawa in 1954.

Website: http://en.

Media Contact

Ippei Maruyama

[email protected]

Original Source

http://en.

Related Journal Article

http://dx.