New CRISPR diagnostic test

Credit: Michael Kaminski, MDC

The simplicity of urine sampling has been combined with the excellent sensing abilities of CRISPR to improve diagnostic testing for kidney transplant patients, an international research team reports in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering.

The new test screens for two common opportunistic viruses infecting kidney transplant patients, cytomegalovirus (CMV) and BK polyomavirus (BKV), and CXCL9 mRNA, whose expression increases during acute cellular kidney transplant rejection.

“Most people think of gene editing when they think of CRISPR, but this tool has great potential for other applications, especially cheaper and faster diagnostics,” said Dr. Michael Kaminski, who heads the Kidney Cell Engineering and CRISPR Diagnostics Lab at the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) and Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. He spearheaded the test’s development while at the Collins lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Since 2020 Kaminski, who is a medical doctor at Charité’s Medical Department, Division of Nephrology and Internal Intensive Care Medicine, started a new lab at the Berlin Institute for Molecular Systems Biology (BIMSB) from MDC.

Critical need

Kidney transplant patients are on medications suppressing their immune systems to reduce the chance the organ will be rejected. But this increases their risk of getting sick from infections. Closely monitoring patients for both infection and rejection is critical and guides the delicate balance of care. Usually this is done via blood tests and kidney biopsies, which are time-consuming, more invasive and expensive.

While affordable urine-based diagnostic tests are available for a variety of biomarkers, from diabetes to pregnancy, they have not been widely adapted for nucleic acids, such as DNA or RNA. That’s where CRISPR comes in.

CRISPR technology is able to find very small segments of a DNA or RNA sequence guided by a complimentary piece of RNA. It works in tandem with certain types of Cas proteins, which cut the target sequence, as well as a fluorescent reporter molecule. This so-called collateral cleavage releases fluorescence, indicating presence of a target. Many labs have been investigating CRISPR’s diagnostic potential on synthetic material, but few have tested real clinical samples.

“The challenge is getting down to concentrations that are clinically meaningful,” Kaminski said. “It really makes a huge difference if you are aiming for a ton of synthetic target in your test tube, versus if you want to get to the single molecule level in a patient fluid.”

Positive or negative

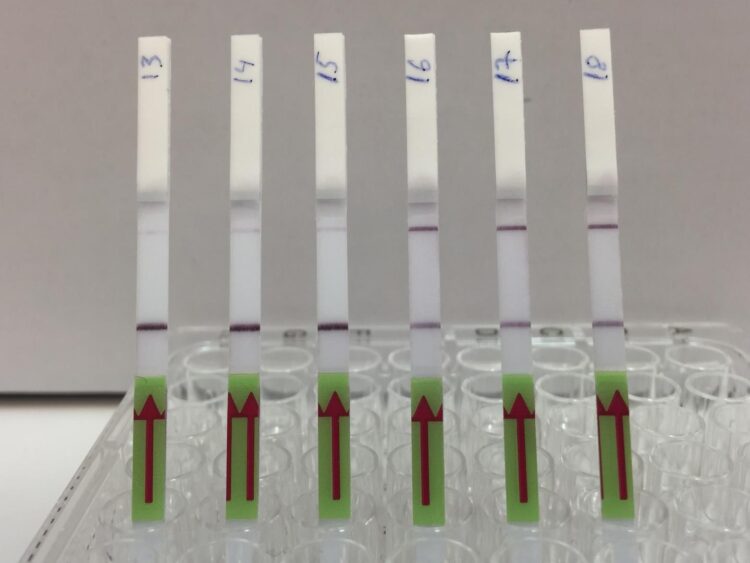

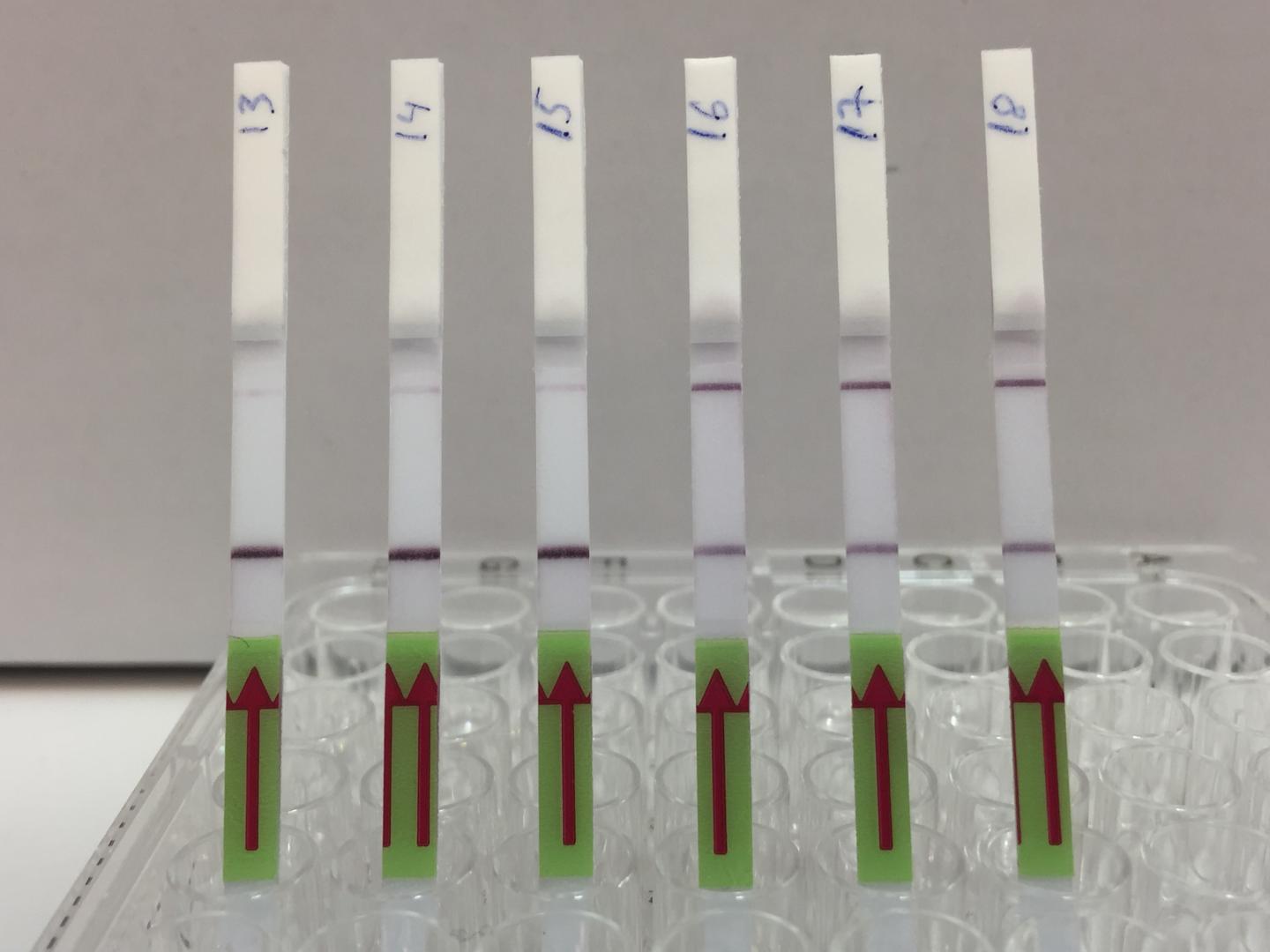

The test kit, formally called an assay, uses a two-step process. First, viral target DNA in a urine sample must be amplified – copied enough times so CRISPR can detect it even if there is just one target molecule present. The team used a specific CRISPR-Cas13 protocol known as SHERLOCK to optimize the process for viral DNA. The results are conveyed much like a home pregnancy test. When a paper strip is dipped in the prepared sample, if only one line appears on the strip, the result is negative, while two lines indicates a virus is present. “It’s exciting to see the results appear on the test strips,” said Robert Greensmith, a first-year PhD student in Kaminiski’s Lab and paper co-author. “As someone new to working with CRISPR, I’m impressed by how it makes for a such a robust testing platform.”

For very low target concentrations, often a pale second line appears on the test strip, which could cause confusion. So, the team developed a smartphone app that unbiasedly analyzes pictures of the test strip and renders the final call based on the line’s intensity.

The researchers used a similar process for the rejection marker CXCL9. There, mRNA was isolated and amplified, followed by CRISPR-Cas13 mediated target detection.

After a lot of work to optimize the technique, the researchers used their assay to analyze more than 100 samples from kidney transplant patients. The assay was very accurate even with low levels of BKV or CMV infection, and correctly detected signs of acute cellular transplant rejection.

Next steps

While a patent application is pending, Kaminski, who is a medical doctor and clinical researcher, is interested in larger clinical studies comparing the assay to conventional monitoring methods. He would also like to investigate ways to make the test even more streamlined. Right now, samples must be heated for preparation and the test requires multiple steps. While it could be used in a hospital setting, it’s not quite ready for at-home testing. The ultimate goal is a one-step process that can quantitatively measure multiple parameters. That way, patients can measure specific changes against their individual baselines.

Kaminski notes this test could also be useful for other immunocompromised people at risk for viral infections, while the CRISPR-based diagnostic approach could potentially be adapted for other organ transplants.

###

Contacts

Dr. Michael M. Kaminski

Head of the lab “Kidney Cell Engineering & CRISPR Diagnostics”

Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC)

[email protected]

Charité – Universtätsmedizin Berlin

Medical Department, Division of Nephrology and Internal Intensive Care Medicine on Campus Charité Mitte

[email protected]

Christina Anders

Editor, Communications Department

Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC)

+49 (0)30 9406 2118

[email protected] or [email protected]

Manuela Zingl

Corporate Spokesperson

Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin

+49 30 450 570 400

[email protected]

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC)

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) was founded in Berlin in 1992. It is named for the German-American physicist Max Delbrück, who was awarded the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine. The MDC’s mission is to study molecular mechanisms in order to understand the origins of disease and thus be able to diagnose, prevent and fight it better and more effectively. In these efforts the MDC cooperates with the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) as well as with national partners such as the German Center for Cardiovascular Research and numerous international research institutions. More than 1,600 staff and guests from nearly 60 countries work at the MDC, just under 1,300 of them in scientific research. The MDC is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (90 percent) and the State of Berlin (10 percent), and is a member of the Helmholtz Association of German Research Centers. http://www.

Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin

Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin is one of the largest university hospitals in Europe, boasting approximately 100 departments and institutes spread across 4 separate campuses. The hospital offers a total of 3,001 beds and, in 2018, treated 152,693 in- and day case patients, in addition to 692,920 outpatients.

At Charité, the areas of research, teaching and medical care are closely interlinked. With approximately 18,000 members of staff employed across its group of companies, Charité is one of the largest employers in Berlin. Approximately 4,500 of its employees work in the field of nursing, with a further 4,300 working in research and medical care.

In 2018, Charité recorded a turnover of more than €1.8 billion, and set a new record by securing more than €170.9 million in external funding. Charité’s Medical Faculty is one of the largest in Germany, educating and training more than 7,500 medical and dentistry students. Charité also offers 619 training positions across 9 different health care professions. http://www.

This is a joint press release by MDC and Charité.

Further information

Kaminski Lab at the MDC

Collins Lab at MIT

MINT-EC Digital Forum: An intern at Kaminski Lab

Media Contact

Michael M. Kaminski

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.