The ruby red rows of tomatoes at the local grocery store don’t come off the vine in such a pretty state. Food producers pick fruits while unripe and later douse them with ethylene, a gas that plants naturally produce to trigger ripening. The ethylene used by food producers comes from cracking fossil fuels. As a green alternative, Cristina Del Bianco of the University of Trento, in Italy, and her team bioengineered Escherichia coli to produce ethylene to accelerate fruit ripening (ACS Synth. Biol. 2014, DOI: 10.1021/sb5000077).

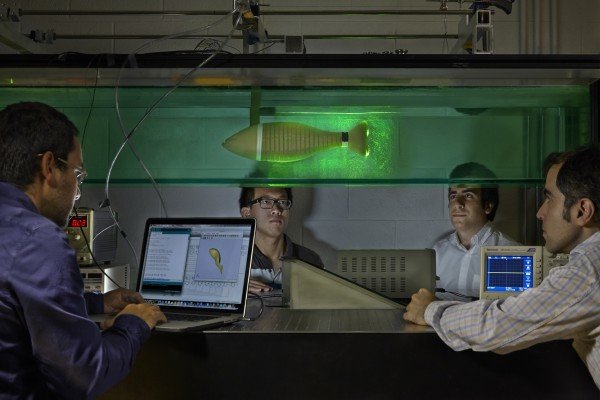

Researchers grew cultures of ethylene-producing bacteria in flasks connected to jars containing unripe fruits such as cherry tomatoes, pears, apples, and bananas. The ethylene helped ripen the fruit. Photo Credit: Laboratory of Cristina Del Bianco

To program E. coli to make the gas, the scientists turned to another microbe called Pseudomonas syringae. This plant pathogen has an enzyme that converts 2-oxoglutarate, a citric acid cycle intermediate, to ethylene in a single step. The researchers inserted the gene into E. coli so that they could turn it on in the presence of the sugar arabinose. When they added arabinose to liquid cultures of the bacteria, ethylene levels in the flasks reached 100 ppm.

Next, the researchers grew the bacteria in flasks connected to jars filled with unripe cherry tomatoes, kiwis, or apples. After eight days, the fruits connected to flasks that received a dose of arabinose were significantly riper than those connected to bacterial cultures that didn’t get the sugar. The tomatoes were redder, the kiwis were softer, and the apples had less starch—a signature of ripening.

To make ethylene production easier for commercial applications, the team reengineered the bacteria so that they expressed the ethylene gene when exposed to blue light. The researchers detected 92 ppm of ethylene in a culture of these bacteria grown in blue light, whereas no ethylene was detected from bacteria grown in the dark.

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by American Chemical Society, Erika Gebel Berg.