Disease-causing bacteria stink — literally — and the odor released by some of the nastiest microbes has become the basis for a faster and simpler new way to diagnose blood infections and finger the specific microbe, scientists reported in Indianapolis today at the 246th National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS).

The new test produces results in 24 hours, compared to as much as 72 hours required with the test hospitals now use, and is suitable for use in developing countries and other areas that lack expensive equipment in hospital labs.

“We have a solution to a major problem with the blood cultures that hospitals have used for more than 25 years to diagnose patients with blood-borne bacterial infections,” said James Carey, Ph.D., who presented the report. “The current technology involves incubating blood samples in containers for 24-48 hours just to see if bacteria are present. It takes another step and 24 hours or more to identify the kind of bacteria in order to select the right antibiotic to treat the patient. By then, the patient may be experiencing organ damage, or may be dead from sepsis.”

Sepsis, or blood poisoning, is a toxic response to blood-borne infections that kills more than 250,000 people each year in the United States alone. The domestic health-care costs to treat sepsis exceed $20 billion. In such a medical emergency, every minute counts, Carey explained, and giving patients the right antibiotics and other treatment can save lives.

That’s why a research team at the University of Illinois that included chemistry professor Ken Suslick, and Carey, set out to develop a faster, simpler test. Carey, of the National University of Kaohsiung in Taiwan in the Republic of China, described a completely new way to identify bacteria compared to an earlier version of such a test developed at Illinois.

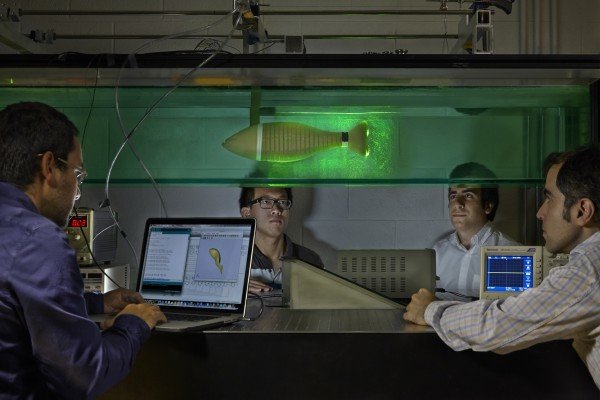

The new device consists of a plastic bottle, small enough to fit in the palm of a hand, filled with nutrient solution for bacteria to grow. Attached to the inside is a chemical sensing array (CSA), an “artificial nose,” with 36 pigment dots. The dots change color in response to signature odor chemicals released by bacteria.

Using the device is simple, Carey said. A blood sample from a patient is injected into the bottle, which goes onto a simple shaker device to agitate the nutrient solution and encourage bacterial growth. Any bacteria present in the blood sample will grow and release a signature odor that changes the colors of pigment dots on the sensor. The test is complete within a day, and the results can be read in a pattern of color changes unique to each strain of bacteria.

The earlier device could detect odors given off by bacteria only after the bacteria were first grown in laboratory culture dishes. That device used a solid nutrient culture material, which takes longer to grow bacteria than the liquid in the improved test. It also was less sensitive and worked only when larger numbers of bacteria were previously cultivated.

Carey said the new device can identify eight of the most common disease-causing bacteria with almost 99 percent accuracy under clinically relevant conditions. Other microbes can cause sepsis, and the scientists are working to expand the test’s capabilities. But Carey said the device could make an impact now in reducing the toll of sepsis, especially in developing countries or other medically underserved areas.

“Our CSA blood culture bottle can be used almost anywhere in the world for a very low cost and minimal training,” Carey noted. “All you need is someone to draw a blood sample, an ordinary shaker, incubator, a desktop scanner and a computer.”

Carey’s research was funded by ChemSensing, Inc., Oklahoma City University, the National Kaohsiung University and the National Science Council of Taiwan. It builds upon Suslick’s research funding from the Genes, Environment and Health Initiative of the National Institutes of Health.

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by American Chemical Society (ACS).