Credit: Baylor College of Medicine

Unraveling the complexity of cancer biology can lead to the identification new molecules involved in breast cancer and prompt new avenues for drug development. And proteogenomics, an integrated, multipronged approach, seems to be a way to do it.

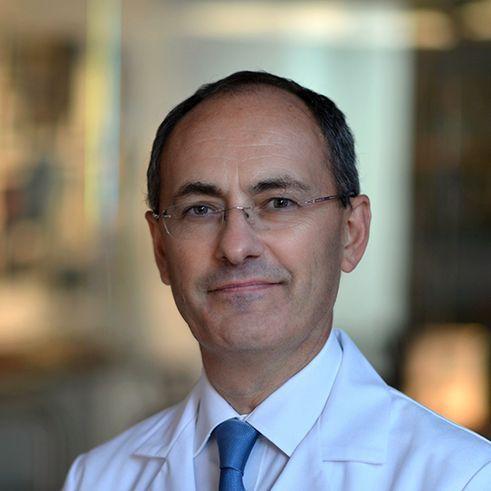

“Our approach to finding new treatments for cancer is to conduct integrated analyses of multiple components of tumor biology through the study of tumor DNA, RNA, proteins and phosphoproteins (proteins tagged with a phosphate chemical group) in order to find targets that are present in only one breast cancer subtype. We then investigate whether these ‘proteogenomic’ subtype outliers could be contributing to the disease in unique ways,” said Dr. Matthew Ellis, professor and director of the Lester and Sue Smith Breast Center, McNair scholar and associate director of precision medicine at the Dan L Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center at Baylor College of Medicine.

Such analyses pointed to DPYSL3 as a molecule whose expression was altered at multiple levels — RNA, protein and phosphoprotein — in a particular type of breast cancer called Claudin-Low triple-negative breast cancer. Having alterations at multiple levels makes DPYSL3 a good candidate for further laboratory studies searching for new therapies for this aggressive and highly metastatic breast cancer subtype.

“When we knocked down gene DPYSL3 in breast cancer cells in the lab, we observed a complex response,” Ellis explained. “The cells stopped dividing properly and accumulated nuclei due a failure to undergo cell division. However, cells without DPYSL3 also became more mobile. These results told us that DPYSL3 affects cell proliferation and the ability to move and metastasize, but in opposite ways.”

The vimentin connection

The researchers then focused on exploring how DPYSL3 mediated its effects on cell division. They focused on vimentin because a recent report indicated that another compound interacting with vimentin had similar effects on cell division as the one observed in the DPYL3 knockdown. Vimentin expression also is a feature of highly aggressive breast cancers.

“It appears that Claudin-Low triple-negative breast cancer cells require low levels of vimentin tagged with a phosphate group to successfully complete cell division,” Ellis said. “When we knocked down DPYSL3, vimentin levels rose and cell division malfunctioned,” Ellis said. “These finding suggests that cancer cells expressing DPYLS3 could be treated with a drug that inhibits the removal of phosphate groups from vimentin.”

Regarding the effects of DPYSL3 on cell motility, Ellis explains that DPYSL3 is known to regulate PAK kinases, a group of enzymes that are important for the cell’s ability to move and undergo the metastatic transition. “When DPYSL3 is suppressed, PAK becomes more active and the cells more metastatic.”

These findings have opened a new avenue that might treat the most aggressive forms of breast cancer by combined targeting of the mechanisms that connect DPYSL3 with vimentin and PAK kinases.

“This work shows the tremendous value of proteogenomics in the identification of new molecules involved in breast cancer that could lead to novel treatments,” Ellis said. “Baylor College of Medicine is a world leader in proteogenomic approaches to translational medicine, which is at the core of the precision medicine approach we are developing.”

Interested in reading all the details of this work> Find them in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

###

Other contributors to this work include Ryoichi Matsunuma, Doug W. Chan, Beom-Jun Kim, Purba Singh, Airi Han, Alexander B. Saltzman, Chonghui Cheng, Jonathan T. Lei, Junkai Wang, Leonardo Roberto da Silva, Ergun Sahin, Mei Leng, Cheng Fan, Charles M. Perou and Anna Malovannaya. The authors are affiliated with one or more of the following institutions: Baylor College of Medicine; Hamamatsu University School of Medicine, Japan; University Wonju College of Medicine, Korea; State University of Campinas-UNICAMP, Brazil; University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; and Hamamatsu Oncology Center, Japan.

This work was primarily supported by Cancer Prevention Institute of Texas Recruitment of Established Investigators Award RR14033, the McNair Foundation and the Eads Fund for Metastatic Breast Cancer Research. Additional support was provided by Susan G. Komen for the Cure Grants BCTR0707808, KG090422, and PG12220321; Clinical and Translational Science Award Grant UL1 RR024992; the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, the National Cancer Institute Breast SPORE Program Grants P50-CA58223, R01-CA148761 and Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium funding, including U01CA214125 and U24 CA160035.

Media Contact

Allison Mickey

[email protected]

713-798-4710

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.