Study finds mixed feelings about using age, life expectancy and risk calculators to guide screening decisions

Credit: University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center

ANN ARBOR, Michigan — Get screened. Screening saves lives. It’s a simple message, but as screening recommendations become more complicated, what happens when the message becomes “maybe get screened” or even “stop screening”?

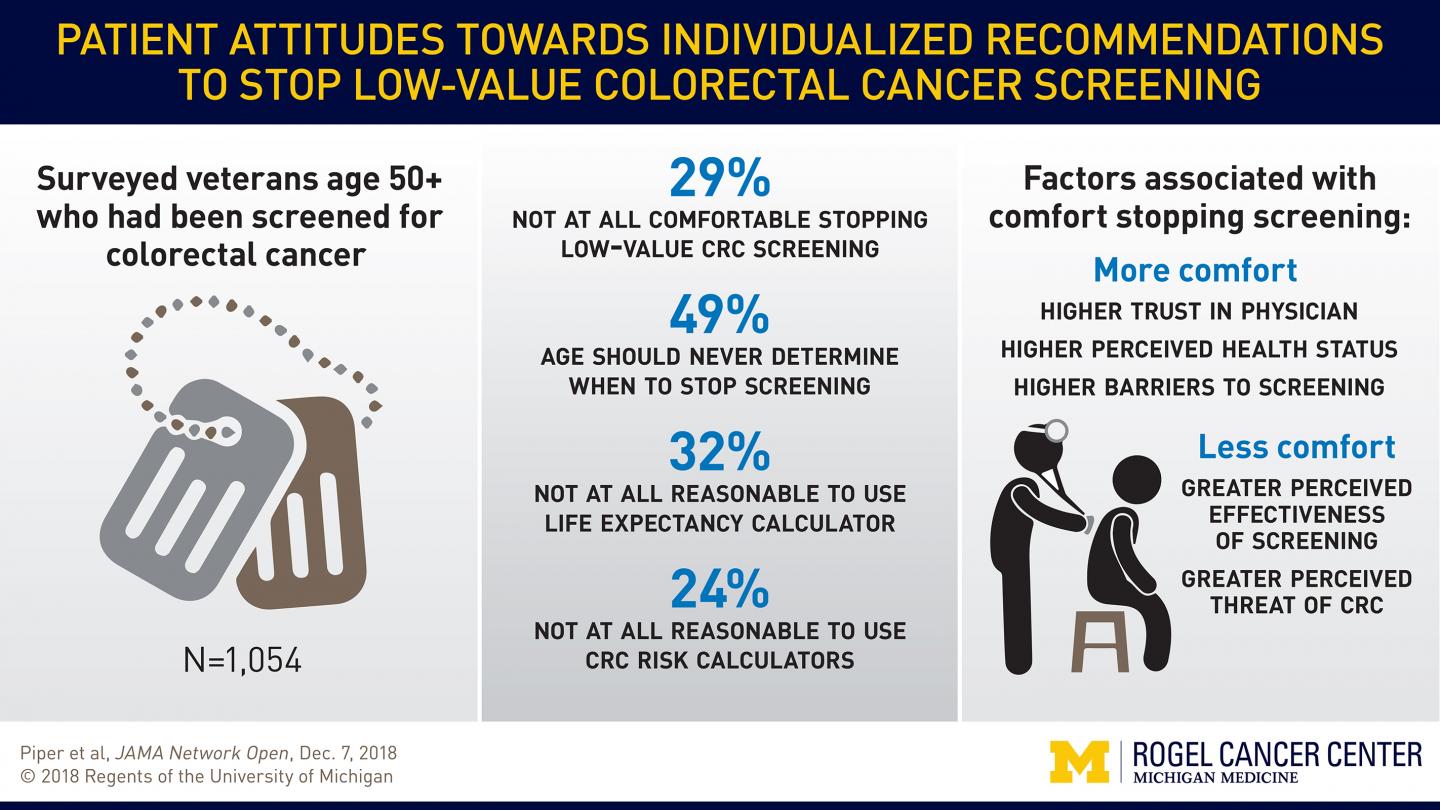

A new study finds 29 percent of veterans who underwent recommended screening colonoscopies were uncomfortable with the idea of stopping these screenings when the benefit was expected to be low for them personally.

“The ‘get screened’ message is simple, aimed at getting people to complete the prevention task. But prevention is only part of the story,” says senior study author Sameer Saini, M.D., M.S., associate professor of gastroenterology at Michigan Medicine and a research scientist at the VA Ann Arbor Center for Clinical Management Research.

“If a person’s risk of colorectal cancer is really, really low, screening is not going to help that person. Also, cancers take time to develop into something that causes symptoms or death. If someone’s life expectancy is limited, identifying cancer and treating it may not improve or extend their life,” he says.

Saini and colleagues surveyed 1,054 veterans who had recently received a screening colonoscopy. Participants were given a hypothetical scenario that explains current age-based colorectal cancer screening recommendations and how health care providers might use risk calculators for life expectancy, colorectal cancer risk and overall benefit of screening to help guide who needs screening.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force guidelines recommend tailoring colorectal cancer screening for people age 76-85 based on overall health, which indicates their life expectancy, and their prior screening history, which indicates their risk of developing colorectal cancer. This study, published in JAMA Network Open, is one of the first to assess patient attitudes toward discontinuing screening based on risk calculators.

Participants were asked how comfortable they would be with not undergoing screening colonoscopies if they had other serious health problems and their doctor recommended against screening. 29 percent said they would be not at all comfortable, while 13 percent said they would be extremely comfortable.

Further, 29 percent said they would go against their doctor’s recommendation in this scenario and continue with screening.

“We need to build the bridge between how we think about screening as experts, based on data and overall benefit, and how our patients think about screening, which is often driven by emotion and other core beliefs. Data can provide our patients with a better sense of the risks and benefits, but we may be delivering a message that is fundamentally at odds with their attitudes and preferences,” says lead study author Marc S. Piper, M.D., M.Sc., a former gastroenterology fellow at Michigan Medicine who is now a gastroenterologist at Digestive Health Associates and assistant professor of medicine at Michigan State University.

More than a third of participants were hesitant about using age to decide when to stop colorectal cancer screening. Participants also expressed distrust about the accuracy of life expectancy calculators or colorectal cancer risk calculators.

“People don’t trust our ability to predict the future. Also, as others have shown, talking about life expectancy can be uncomfortable. We need to shift the conversation to talk about the benefits of screening, rather than life expectancy, or we risk turning people off,” Piper says.

Participants who were more comfortable with stopping screening had more trust in their physician and rated their own health more highly. Those with high barriers to screening also were more comfortable with stopping. On the other hand, the more people perceived screening to be effective and colorectal cancer to be a threat, the more likely they were to be uncomfortable with stopping screening.

“It is important for us to start thinking about what type of information we are giving patients that is informing or building their mental models about screening. If we were doing our job right, it would not be a surprise to them that screening might not be beneficial across their whole lifespan,” Saini says.

The authors suggest doctors explain before someone’s first screening colonoscopy that the benefit changes over the lifespan. As a person gets older, these screenings will provide more information about their risk of developing cancer and in time some might not need to continue screening.

“As we move toward personalized screening recommendations, we must consider how patients think about cancer prevention. If we communicate these ideas up front, it may be less jarring when the screening message changes later in life,” Piper says.

###

Additional authors: Jennifer K. Maratt, Brian J. Zikmund-Fisher, Carmen Lewis, Jane Forman, Sandeep Vijan, Valbona Metko

Funding: Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development grant VA CDA 09-213-2, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases NIDDK T32 DK062708

Disclosure: None

Reference: JAMA Network Open, published Dec. 7, 2018

Resources:

University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center, http://www.

Michigan Health Lab, http://www.

Michigan Medicine Cancer AnswerLine, 800-865-1125

Media Contact

Nicole Fawcett

[email protected]

734-764-2220

News source: https://scienmag.com/