Recording the electrostatic energy of honeybee hives offers a ‘canary in the coalmine’ look into ecosystem threats and environmental conditions

Credit: Benjamin H. Paffhausen, Julian Petrasch, Uwe Greggers et al.

Honeybees have a complex communication system. Between buzzes and body movements, they can direct hive mates to food sources, signal danger, and prepare for swarming – all indicators of colony health. And now, researchers are listening in.

Scientists based in Germany – with collaborators in China and Norway – have developed a way to monitor the electrostatic signals that bees give off. Basically, their wax-covered bodies charge up with electrostatic energy due to friction when flying, similar to how rubbing your hair can make it stand on end. That energy then gets emitted during communications.

“We were thrilled by the potential of directly accessing the social communication of bees with our method,” says Dr. Randolf Menzel, of the Free University of Berlin. “For the first time we can ask the bees themselves whether their colony is in a healthy condition or whether they suffer from unfavorable environmental conditions including those caused by humans.”

The paper, recently published in the open access journal Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, likens honeybee colonies to a canary in a coal mine. Bees are usually among the first species to be affected by pollutants such as insecticides, and weakened communications can signal their damaging effects. Such evidence may point to potential harm to other wildlife and ecosystems in a way that is quicker and cheaper than other methods.

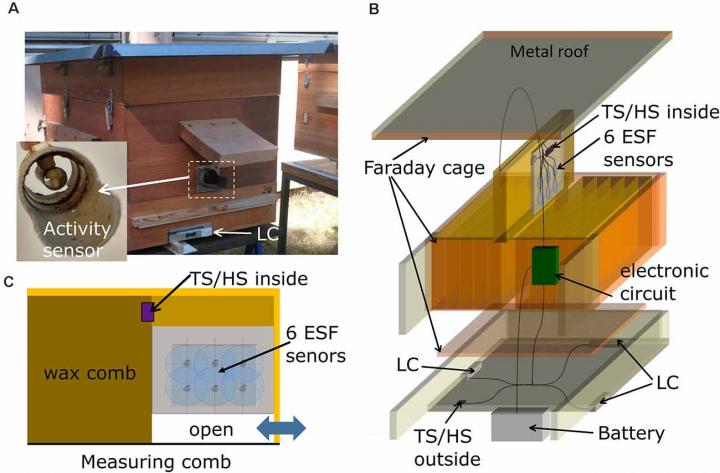

Menzel and his colleagues worked with 30 beekeepers across Germany over a period of five years. They placed sensors and a central recording device inside and outside a specially designed hive, and monitored the honeybees’ electrostatic field (ESF) data.

They were particularly interested in what is known as the “waggle dance,” a sophisticated messaging system in which honeybees walk in a figure-eight pattern, then “waggle” back and forth through the stretched part of the intersection. This bee ballet communicates flight directions and distance. “Other bees follow the dancing bee, read the message of the dancer, and apply the information about distance and direction to an attractive food source in their outbound flights,” says Menzel.

The primary purpose of their research study was to measure the feasibility of their recording system, which did indeed work, although Menzel notes that scaling up their system would be challenging, and “to get meaningful knowledge about the impact of pesticides and health conditions of bees in a larger area, we will have to use many devices across that area.”

Still, the researchers learned more about hive communication, and found what Menzel described as “unexpected phenomena.” For example, they found that bees perform waggle dances at night as well as during the day, and that insecticides used for treatment against pest mites had a negative impact on honeybees’ communication. They also found that ESF signals were emitted in preparation of swarming, and that their strength didn’t depend on environmental conditions such as humidity and UV radiation.

Menzel says that their system collected a large amount of data, and that they need further studies to improve and finetune interpretation. “So far we have only begun to apply machine learning algorithms to separate and quantify the electrostatic field signals.” In the future though, it’s possible that eavesdropping on bees may provide rich and important information beyond the local pollen hotspot. Their communications could be crucial in understanding – and protecting – whole ecosystems.

###

Media Contact

Mischa Dijkstra

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.