Credit: Dimitrov et al., 2019

Researchers in Germany have discovered why sleep can sometimes be the best medicine. Sleep improves the potential ability of some of the body’s immune cells to attach to their targets, according to a new study that will be published February 12 in the Journal of Experimental Medicine. The study, led by Stoyan Dimitrov and Luciana Besedovsky at the University of Tübingen, helps explain how sleep can fight off an infection, whereas other conditions, such as chronic stress, can make the body more susceptible to illness.

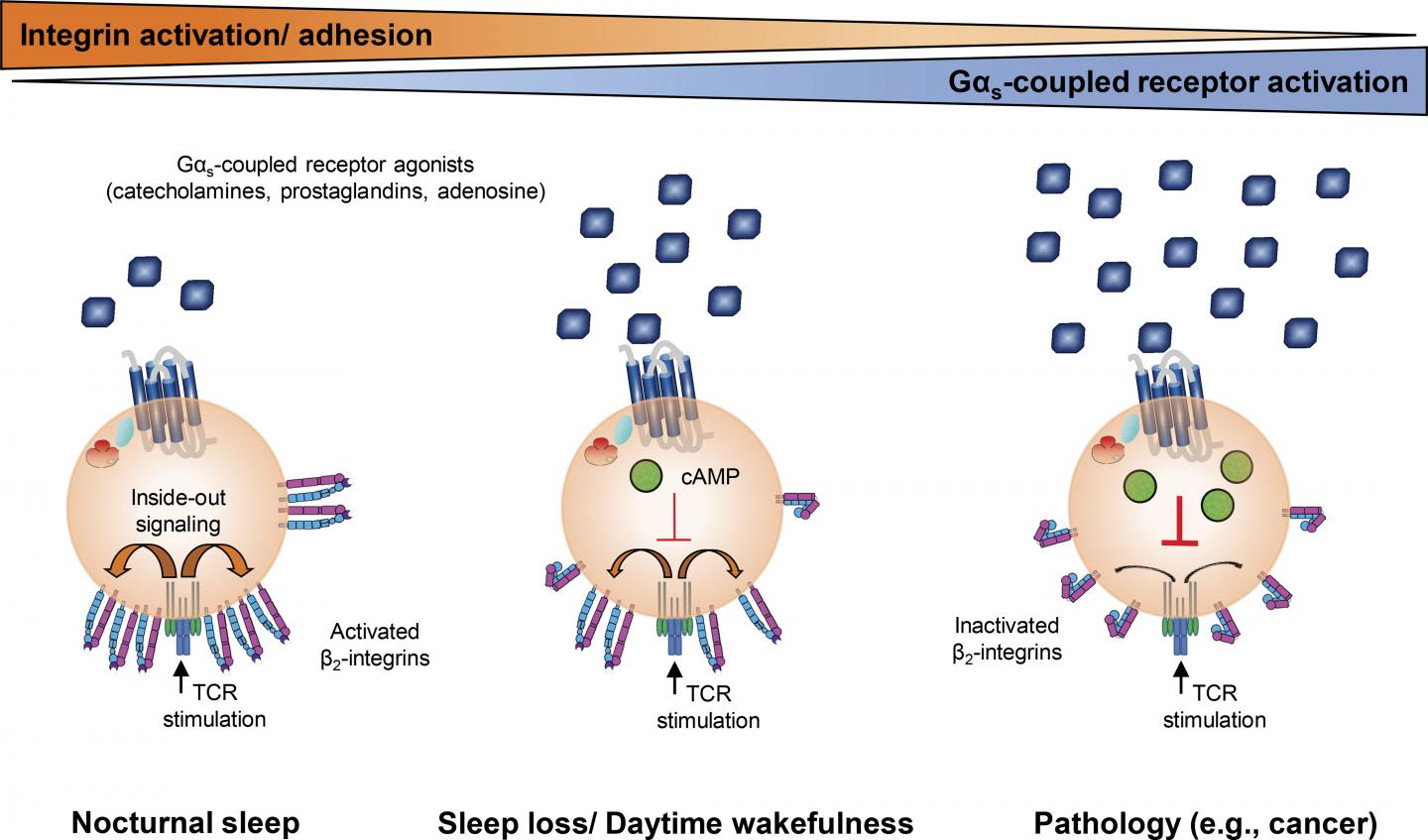

T cells are a type of white blood cell that are critical to the body’s immune response. When T cells recognize a specific target, such as a cell infected with a virus, they activate sticky proteins known as integrins that allow them to attach to their target and, in the case of a virally infected cell, kill it. While much is known about the signals that activate integrins, signals that might dampen the ability of T cells to attach to their targets are less well understood.

Stoyan Dimitrov and colleagues at the University of Tübingen decided to investigate the effects of a diverse group of signaling molecules known as Gαs-coupled receptor agonists. Many of these molecules can suppress the immune system, but whether they inhibit the ability of T cells to activate their integrins and attach to target cells was unknown.

Dimitrov and colleagues found that certain Gαs-coupled receptor agonists, including the hormones adrenaline and noradrenaline, the proinflammatory molecules prostaglandin E2 and D2, and the neuromodulator adenosine, prevented T cells from activating their integrins after recognizing their target. “The levels of these molecules needed to inhibit integrin activation are observed in many pathological conditions, such as tumor growth, malaria infection, hypoxia, and stress,” says Dimitrov. “This pathway may therefore contribute to the immune suppression associated with these pathologies.”

Adrenaline and prostaglandin levels dip while the body is asleep. Dimitrov and colleagues compared T cells taken from healthy volunteers while they slept or stayed awake all night. T cells taken from sleeping volunteers showed significantly higher levels of integrin activation than T cells taken from wakeful subjects. The researchers were able to confirm that the beneficial effect of sleep on T cell integrin activation was due to the decrease in Gαs-coupled receptor activation.

“Our findings show that sleep has the potential to enhance the efficiency of T cell responses, which is especially relevant in light of the high prevalence of sleep disorders and conditions characterized by impaired sleep, such as depression, chronic stress, aging, and shift work,” says last author Luciana Besedovsky.

In addition to helping explain the beneficial effects of sleep and the negative effects of conditions such as stress, Dimitrov and colleagues’ study could spur the development of new therapeutic strategies that improve the ability of T cells to attach to their targets. This could be useful, for example, for cancer immunotherapy, where T cells are prompted to attack and kill tumor cells.

###

Dimitrov et al. 2019. J. Exp. Med. http://jem.

About the Journal of Experimental Medicine

The Journal of Experimental Medicine (JEM) features peer-reviewed research on immunology, cancer biology, stem cell biology, microbial pathogenesis, vascular biology, and neurobiology. All editorial decisions are made by research-active scientists in conjunction with in-house scientific editors. JEM makes all of its content free online no later than six months after publication. Established in 1896, JEM is published by Rockefeller University Press. For more information, visit jem.org.

Visit our Newsroom, and sign up for a weekly preview of articles to be published. Embargoed media alerts are for journalists only.

Follow JEM on Twitter at @JExpMed and @RockUPress.

Media Contact

Ben Short

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.