Research answers question on how some magmatic rocks contain random proportions of minerals than what is expected for rocks of their type.

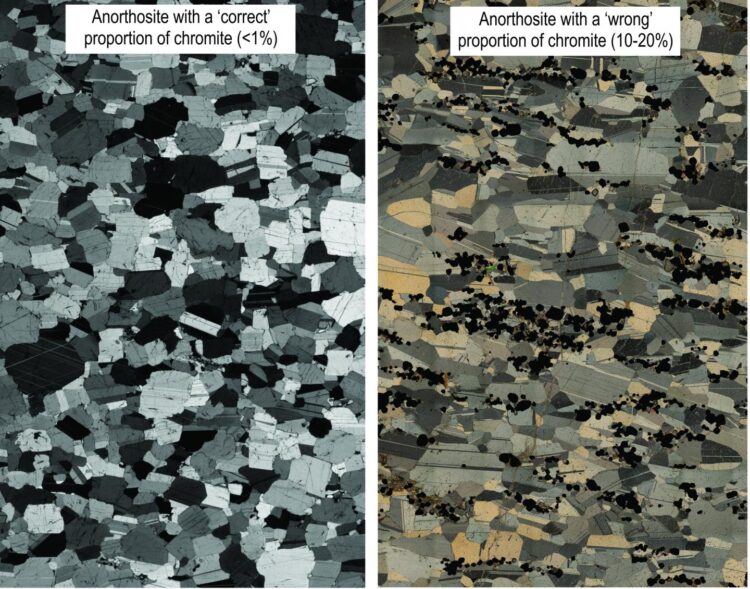

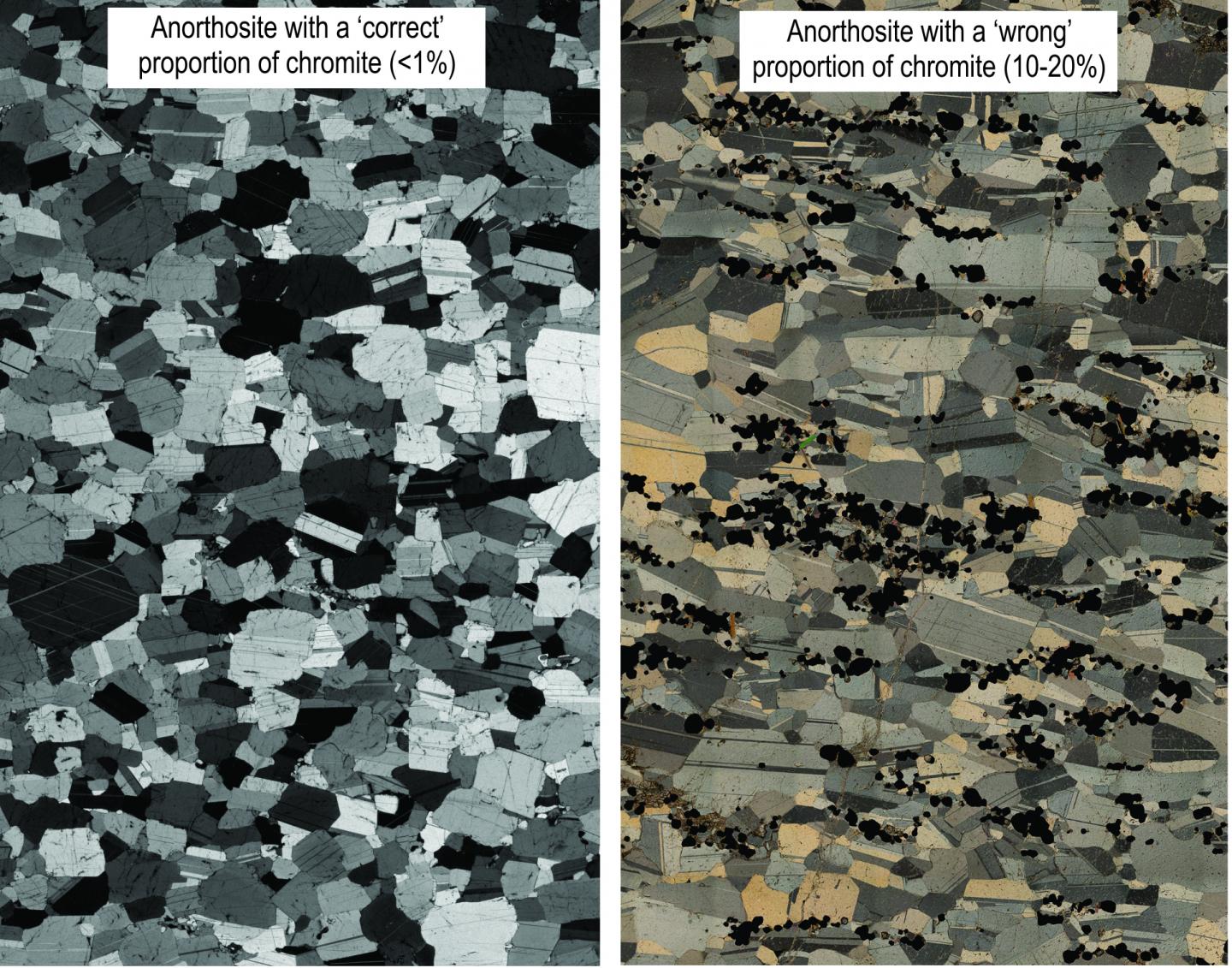

Credit: Wits University

Researchers at Wits University in Johannesburg, South Africa, have found the answer to an enigma that has had geologists scratching their heads for years.

The question is that of how certain magmatic rocks that are formed through crystallisation in magmatic chambers in the Earth’s crust, defy the norm, and contain minerals in random proportions.

Normally, magmatic rocks consist of some fixed proportions of various minerals. Geologists know, for instance, that a certain rock will have 90% of one mineral and 10% of another mineral.

However, there are some magmatic rocks that defy this norm and do not adhere to this general rule of thumb. These rocks, called as non-cotectic rocks, contain minerals in completely random proportions.

One example is chromite-bearing anorthosite from the famous Bushveld Complex in South Africa. These rocks contain up to 15% to 20% of chromite, instead of only 1%, as would normally be expected.

“Traditionally, these rocks with a ‘wrong’ composition were attributed to either mechanical sorting of minerals that crystallised from a single magma or mechanical mixing of minerals formed from two or more different magmas,” says Professor Rais Latypov from the Wits School of Geosciences.

Seeing serious problems with both these approaches, Latypov and his colleague Dr Sofya Chistyakova, also from the Wits School of Geosciences, found that there is actually a simple explanation to this question – and it has nothing to do with the mechanical sorting or mixing of minerals to produce these rocks.

Their research, published in the journal Geology, shows that an excess amount of some minerals contained in these rocks may originate in the feeder conduits along which the magmas are travelling from the deep-seated staging chambers towards Earth’s surface.

“While travelling up through the feeder channels, the magma gets into contact with cold sidewalls and starts crystallising, thereby producing more of the mineral(s) than what should be expected,” says Chistyakova.

The general principle of this approach can be extended to any magmatic rocks with ‘wrong’ proportions of minerals in both plutonic and volcanic environments of the Earth.

“It is possible that a clue to some other petrological problems of magmatic complexes should be searched for in the feeder conduits rather than in magma chambers themselves. This appealing approach holds great promise for igneous petrologists working with basaltic magma complexes,” says Latypov.

###

Media Contact

Schalk Mouton

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.