Being single, remote and lacking a pension also linked to poor access to healthcare

Credit: Shen (Lamson) Lin

A new study, published this week in the International Journal of Health Services, found that older adults without health insurance in China were 35% less likely to receive needed inpatient care compared to those with job-based health insurance.

Shen (Lamson) Lin, a doctoral student at the University of Toronto’s Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work and Institute for Life Course and Aging, investigated 6,570 Chinese adults aged 60 and older using nationally representative data from the 2012 China Family Panel Study (CFPS).

“Disadvantaged older people who bear greater burdens of ill health often hesitate to reach out for essential care due to financial barriers — especially when they are not covered by any health insurance,” says Lin, the study’s sole author.

“This is particularly relevant to the global COVID-19 epidemic. Health insurance gaps and associated financial concerns may mean that high-risk populations, such as impoverished older adults, go undiagnosed and untreated, which could inadvertently contribute to the spread of the virus.”

Around the world older people normally constitute the largest group of health care system users. The study estimated that, in China — which is home to the world’s largest aging population (241 million) — 4.2% of older adults live without health insurance.

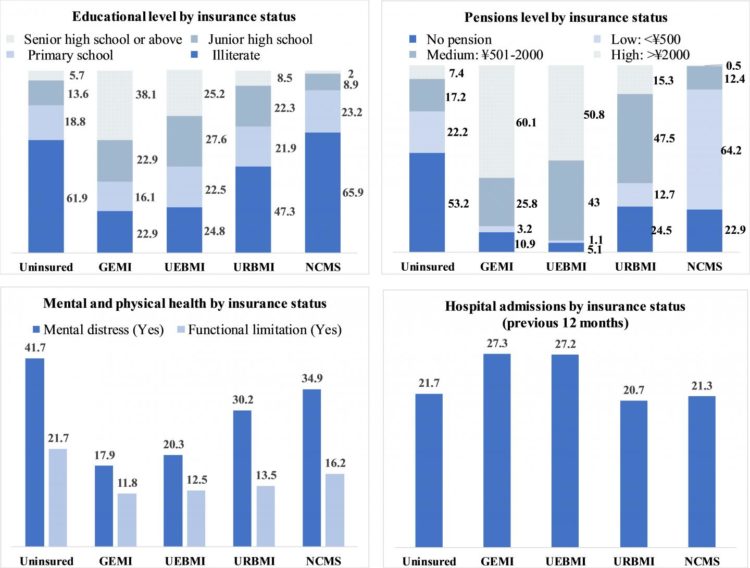

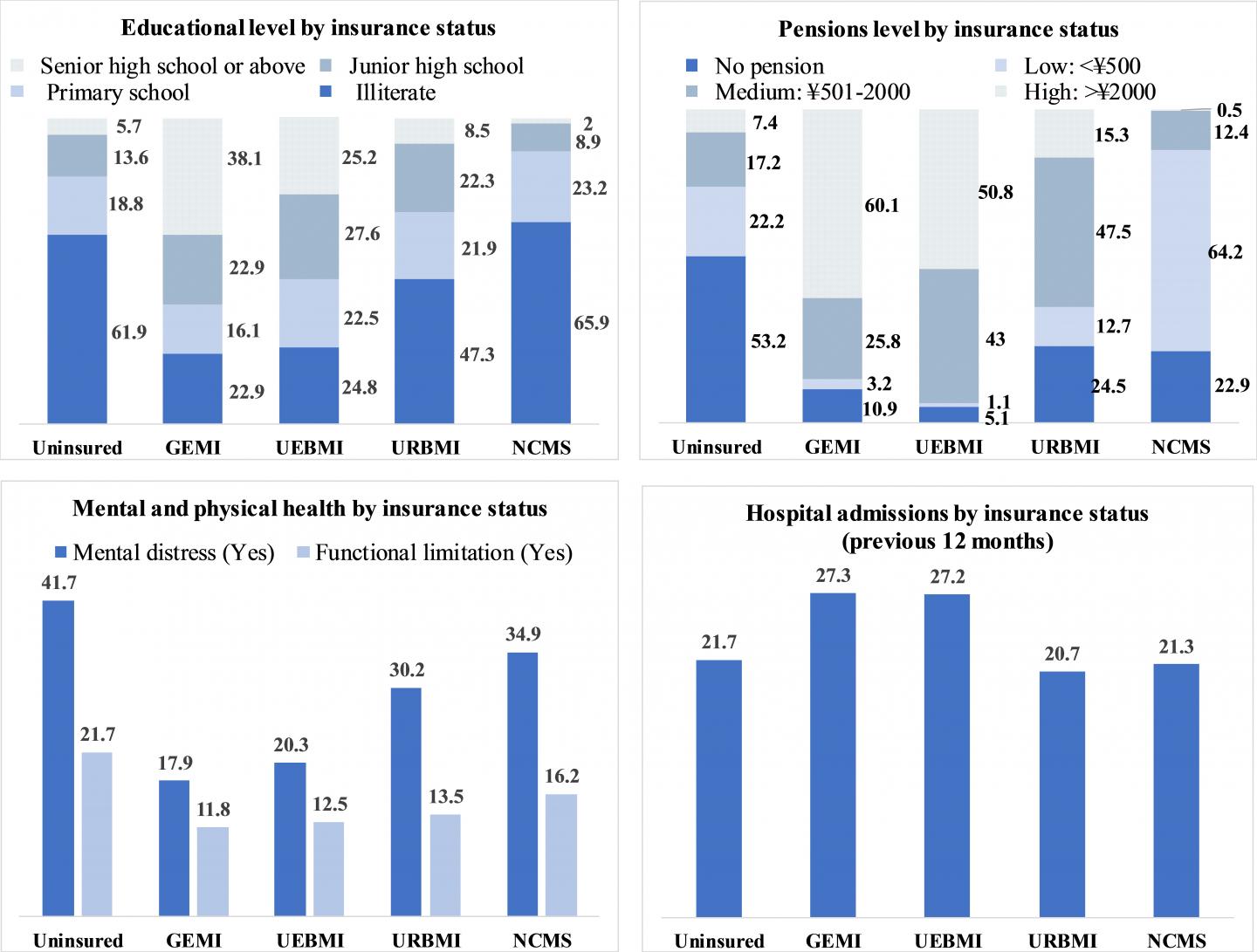

Uninsured seniors were more likely to have poor perceived health (55.3% vs 45.9%) and were more likely to have experienced mental distress (41.7% vs 17.9%) and physical impairment (21.7% vs 11.8%) compared to their insured counterparts with generous coverage.

In addition, the majority of the uninsured older adults were socio-economically vulnerable — 61.9% were illiterate and 53.2% did not have an old-age pension.

“In countries, like China, that lack a universal healthcare system, social health insurance plays an instrumental role in addressing health inequities among under-served populations,” says Lin.

The study also found that older Chinese adults were around twice as likely to visit general hospitals than a community walk-in clinic, which, Lin points out, has implications for cross-cultural health care seeking practice.

“In contrast to the primary-care-based approach in many western developed countries, the service delivery in China is still an acute hospital-centric model and thus a hospital is still in seniors’ priority list when seeking care,” he says. “Chinese immigrants to other countries may maintain a similar pre-migration pattern.”

Multiple risk factors for poor access to hospital services were identified. These included living in a rural area and living without partners or informal caregivers who can provide support. Lacking a pension in later life was also a barrier associated with lower physician visits when older adults felt unwell.

Interestingly, older adults who believed or trusted traditional Chinese medicine were more likely to seek both outpatient and inpatient care.

“The phenomenon of health care inequity is particularly troubling, given that reforms to privatize healthcare are still undergoing,” says Lin. “To make sure no one is left behind, policy efforts should unify and extend the social health insurance system. This will help combat existing insurance-related inequities in health care use, especially for aging populations that are marginalized.”

A copy of the paper is available to credentialed journalists upon request.

###

For more information, please contact:

Shen (Lamson) Lin

Ph.D. Student

Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work

University of Toronto

[email protected]

(647) 230-6802

Media Contact

Shen (Lamson) Lin

[email protected]

647-230-6802

Related Journal Article

http://dx.