Hospitals have put a lot of effort into encouraging good hand hygiene among their staff, but new findings suggest a new frontier for preventing transmission

Credit: University of Michigan

For decades, hospitals have worked to get doctors, nurses and others to wash their hands and prevent the spread of germs.

But a new study suggests they may want to expand those efforts to their patients, too.

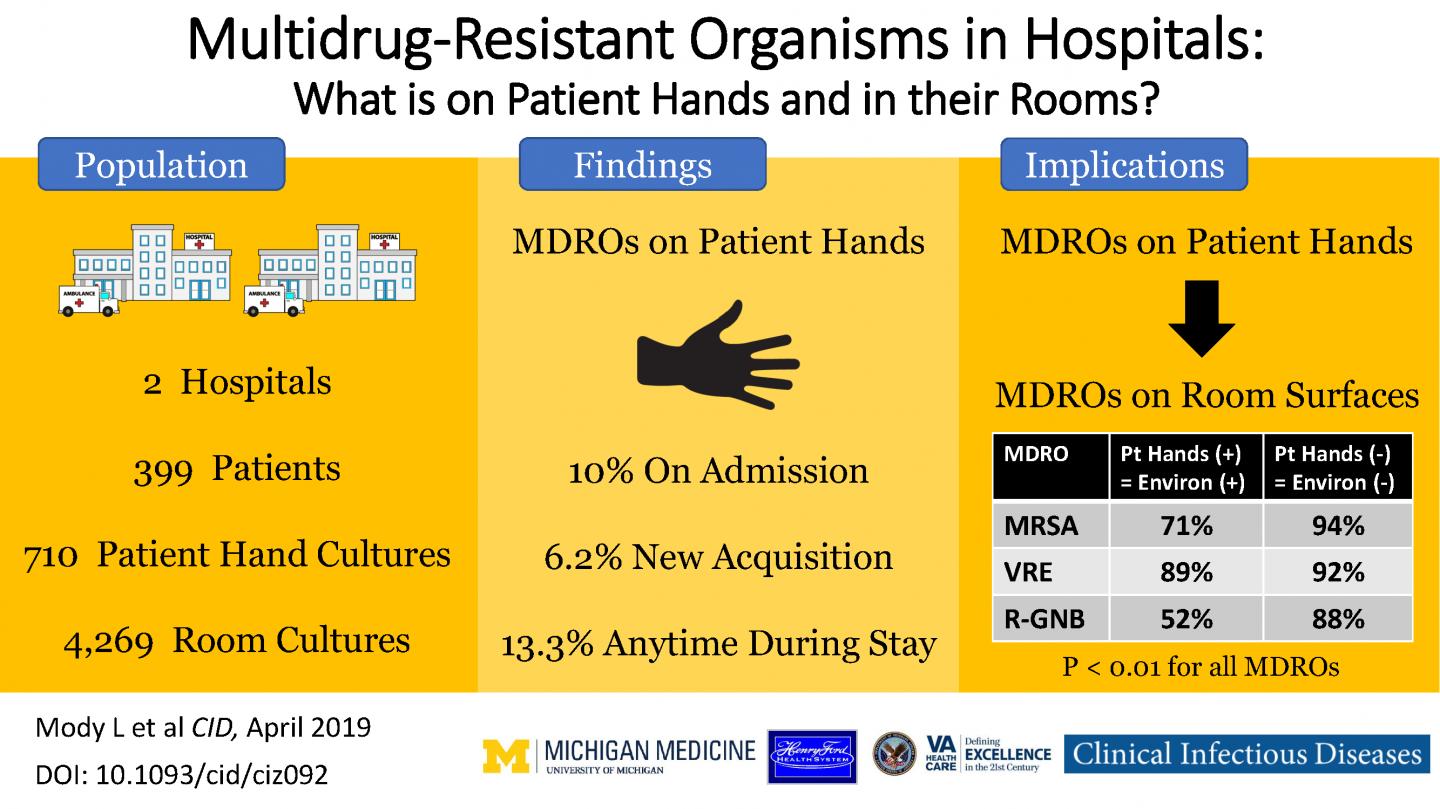

Fourteen percent of 399 hospital patients tested in the study had “superbug” antibiotic-resistant bacteria on their hands or nostrils very early in their hospital stay, the research finds. And nearly a third of tests for such bacteria on objects that patients commonly touch in their rooms, such as the nurse call button, came back positive.

Another six percent of the patients who didn’t have multi-drug resistant organisms, or MDROs, on their hands at the start of their hospitalization tested positive for them on their hands later in their stay. One-fifth of the objects tested in their rooms had similar superbugs on them too.

The research team cautions that the presence of MDROs on patients or objects in their rooms does not necessarily mean that patients will get sick with antibiotic-resistant bacteria. And they note that healthcare workers’ hands are still the primary mode of microbe transmission to patients.

“Hand hygiene narrative has largely focused on physicians, nurses and other frontline staff, and all the policies and performance measurements have centered on them, and rightfully so,” says Lona Mody, M.D., M.Sc., the University of Michigan geriatrician, epidemiologist and patient safety researcher who led the research team. “But our findings make an argument for addressing transmission of MDROs in a way that involves patients, too.”

Studying the spread

Mody and her colleagues report in the new paper in Clinical Infectious Diseases that of the six patients in their study who developed an infection with a superbug called MRSA while in the hospital, all had positive tests for MRSA on their hands and hospital room surfaces.

In addition to MRSA, short for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, the study looked for superbugs called VRE (vancomycin-resistant enterococcus) and a group called RGNB, for resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Because of overuse of antibiotics, these bacteria have evolved the ability to withstand attempts to treat infections with drugs that once killed them.

Mody notes that the study suggests that many of the MDROs seen on patients are also seen in their rooms early in their stay, suggesting that transmission to room surfaces is rapid. She heads the Infection Prevention in Aging research group at the U-M Medical School and VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System.

Additionally, since many patients arrive at the hospital through the emergency room, and may get tests in other areas before reaching their hospital room, it will be important to study the ecology of MDROs in those areas too, she says.

“This study highlights the importance of handwashing and environmental cleaning, especially within a healthcare setting where patients’ immune systems are compromised,” says infectious disease physician Katherine Reyes, M.D., lead author for Henry Ford Health System researchers involved in the study. “This step is crucial not only for healthcare providers, but also for patients and their families. Germs are on our hands; you do not need to see to believe it. And they travel. When these germs are not washed off, they pass easily from person to person and objects to person and make people sick.”

More about the study

The team made more than 700 visits to the rooms of general medicine inpatients at two hospitals, working to enroll them in the study and take samples from their bodies and often-touched surfaces as early as possible in their stay. They were not able to test rooms before the patients arrived, and did not test patients who had had surgery, or were in intensive care or other types of units.

Using genetic fingerprinting techniques, they looked to see if the strains of MRSA bacteria on the patients’ hands were the same as the ones in their rooms. They found the two matched in nearly all cases – suggesting that transfer to and from the patient was happening. The technique is not able to distinguish the direction of transfer, whether it’s from patient to objects in the room, or from those objects to patients.

Cleaning procedures for hospital rooms between patients, especially when a patient has been diagnosed with an MDRO infection, have improved over the years, says Mody, and research has shown them to be effective when used consistently. So lingering contamination from past patients may not have been a major factor.

But the question of exactly where patients picked up the MDROs that were found on their bodies, and were transmitted to the surfaces in their rooms, is not addressed by the current study and would be an important next step based on these results.

Why MDROs matter

Also important, says Mody, is the fact that hospital patients don’t just stay in their rooms – current practice encourages them to get up and walk in the halls as part of their recovery from many illnesses, and they may be transported to other areas of the hospital for tests and procedures.

As they travel, they may pick up MDROs from other patients and staff, and leave them on the surfaces they touch.

So even if a relatively healthy person has an MDRO on their skin, and their immune system can fight it off if it gets into their body, a more vulnerable person in the same hospital can catch it and get sick. The researchers are exploring studying MDROs on patients in other types of hospital units who may be more susceptible to infections.

Patients and staff may also get colonized with MDROs in outpatient care settings that have become the site of so much of American health care, including urgent care centers, freestanding imaging and surgery centers, and others.

Mody and colleagues are presenting new data about MDROs in skilled nursing facilities at an infectious disease conference in Europe in coming days. They showed that privacy curtains – often used to separate patients staying in the same room, or to shield patients from view when dressing or being examined – are also often colonized with superbugs.

“Infection prevention is everybody’s business,” says Mody, a professor of internal medicine at the U-M Medical School. “We are all in this together. No matter where you are, in a healthcare environment or not, this study is a good reminder to clean your hands often, using good techniques–especially before and after preparing food, before eating food, after using a toilet, and before and after caring for someone who is sick– to protect yourself and others.”

###

In addition to Mody and Reyes, the study team includes senior author and HFHS infectious disease physician Marcus Zervos, M.D., U-M and VAAAHS physicians Sanjay Saint and Vineet Chopra, U-M infectious disease physicians Laraine Washer and Keith Kaye, U-M geriatrics research team members Kristen Gibson, Marco Cassone and Julia Mantey; U-M bioinformatics student Jie Cao, HFHS team members Sarah Altamimi and Mary Perri, and Hugo Sax, head of infection control and hospital epidemiology at University Hospital in Zurich, Switzerland. Mody, Kaye, Saint and Chopra are members of the U-M Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation, and the U-M/VA Patient Safety Enhancement Program.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, BAA 200-2016-91954

Reference: Clinical Infectious Diseases, DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciz092

Media Contact

Kara Gavin

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.