Credit: University of Michigan Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation

ANN ARBOR, Mich. – Before leaving the hospital after childbirth, more women are opting to check one thing off their list: birth control.

But access to long-lasting, reversible contraception like an intrauterine device immediately after giving birth may still lag far behind the demand, a new University of Michigan study suggests.

The rate of IUDs or implants after childbirth increased sevenfold over five years — from 1.86 per 10,000 deliveries in 2008 to 13.5 per 10,000 deliveries in 2013 — according to the findings in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Some 96 percent of inpatient postpartum IUDs, however, are placed at urban teaching hospitals, suggesting that the service is not available to women delivering at urban non-teaching and rural hospitals.

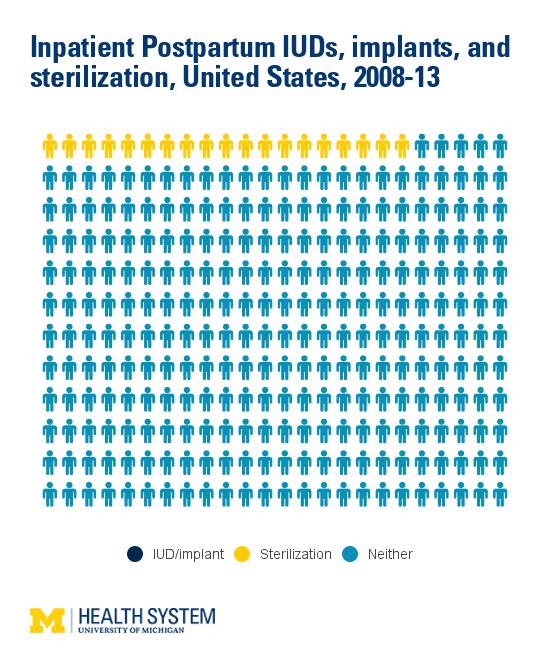

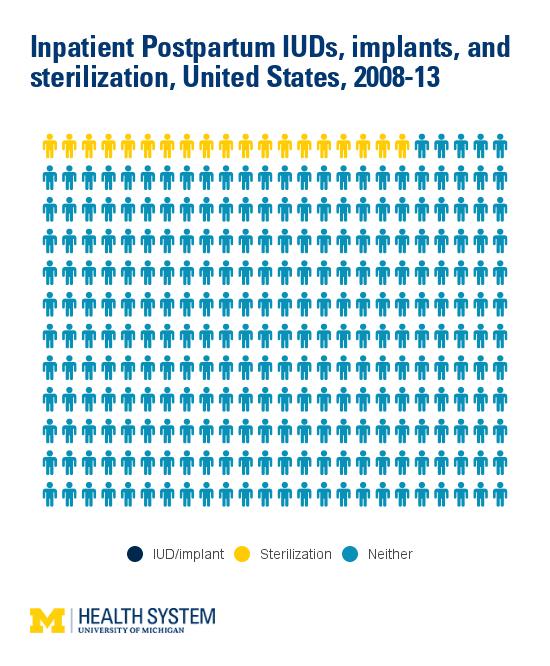

Overall, the rate of patients receiving reversible contraception while hospitalized for a delivery still remained less than 2 percent of the sterilization rate (a permanent procedure to prevent pregnancy.)

"Getting an IUD right after childbirth may be more convenient and less painful than insertion at a later office visit. But we found that access to this service varies greatly depending on where a woman delivers her baby," says lead author Michelle Moniz, M.D. M.Sc., an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology and researcher at the University of Michigan Medical School.

"Maternity clinicians and policymakers should strive to ensure that women have access to the full range of contraceptive options after childbirth and that they are able to make an informed, voluntary, personal choice about whether and when to have another child."

Unintended, repeat pregnancy too close to the birth of a first baby can be dangerous for both moms and babies, with higher likelihood of adverse outcomes such as miscarriage, preterm labor and stillbirth.

Enhancing access to in-hospital reversible contraception and insurance coverage for the service will help prevent such unintended pregnancies, Moniz says. Women using highly effective contraception — including IUDs, implants or tubal sterilization — are four times more likely to achieve adequate birth spacing than women using a barrier or no method. However, few U.S. women use these methods by three months postpartum, partly as a result of poor access.

IUDs inserted immediately after birth have a slightly higher chance of falling out than IUDs inserted four to eight weeks later — but the risk of dangerous complications like infection or injury is exceedingly low with both immediate and delayed placement. Immediate placement is also cost-effective, Moniz says. Contraceptive implants do not have risk of falling out, so they are a particularly attractive option for insertion during the delivery hospitalization.

U-M researchers found that IUD and implant insertions during a maternal hospitalization were more likely among sicker, poorer women delivering at urban teaching hospitals. Eighty-five percent of inpatient postpartum IUDs are provided to women with public or other insurance, including Medicaid, Medicare or self-pay.

Previous studies suggest that many women who say they want an IUD or implant don't make it to a follow-up office appointment to get their preferred method of birth control after having a baby, often due to childcare, transportation and other barriers.

"We know that many women's first choice for birth control is an IUD or implant, which are also the safest and most effective forms of reversible contraception," Moniz says. "We need to remove the barriers that prevent women from getting their preferred method of contraception in a way that's most convenient for them.

"Expanding access to reversible contraception after childbirth will have a far-reaching impact."

###

Media Contact

Beata Mostafavi

[email protected]

734-764-2220

@umichmedicine

http://www.med.umich.edu