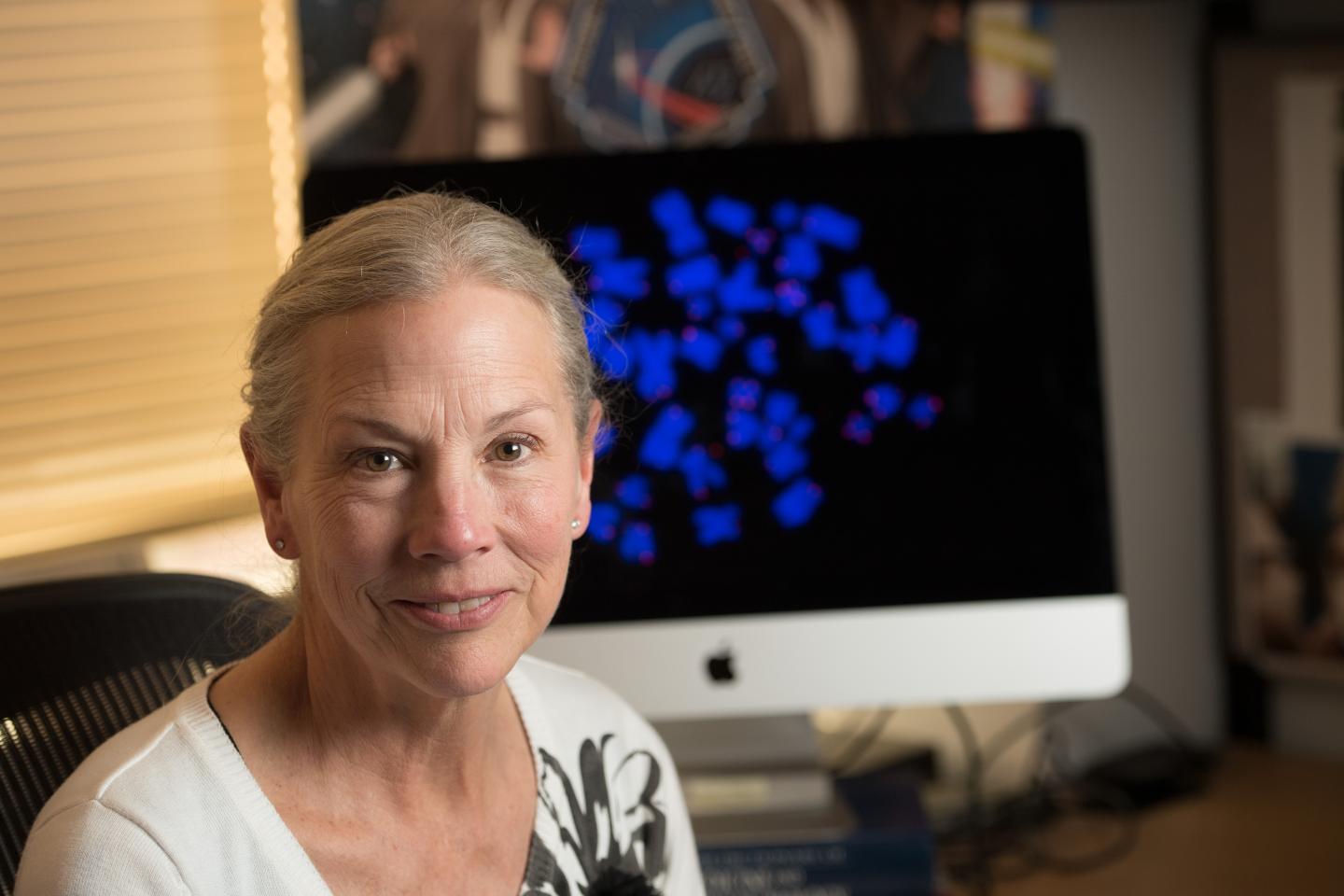

Credit: John Eisele/Colorado State University

When NASA decided to study identical twin astronauts — one remaining on Earth while the other orbited high above for nearly one year, starting in March 2015 — scientists were not sure what they would find.

Would Scott Kelly undergo a Benjamin Button or Interstellar-like effect, and return to Earth younger than his brother Mark?

Based on preliminary results released in January 2017, Colorado State University Professor Susan Bailey, who studies telomeres, or the protective “caps” on the ends of chromosomes, found that Scott’s telomeres in his white blood cells got longer while in space. Changes in telomere length could mean a person is at risk for accelerated aging or the diseases that come along with getting older. Telomeres typically shorten as a person ages.

These findings ran counter to what Bailey thought might occur, and are confirmed in “The NASA Twins Study: A multi-dimensional analysis of a year-long human spaceflight,” published in Science April 12.

To study the twins’ telomeres, Bailey and her team received vials of their blood over 25 months, spanning time points before, during and after spaceflight. Her team processed and analyzed the precious samples, delivered fresh from the space station by Soyuz rocket and overnight couriers.

“We were surprised, that was the first reaction,” said Bailey, when asked how it felt to see the initial findings. “But that’s what science is all about, right?”

Results from the study have implications for astronauts and people who want to explore space in the years to come through private ventures as humankind ventures longer and deeper in space.

NASA has announced plans for a mission to Mars and to a cis-Lunar station (between the Earth and the Moon), which will provide new opportunities for studying what happens to the human body during extended spaceflight.

Twelve universities, more than 80 researchers

Bailey’s project was one of 10 investigations supported by 84 researchers across 12 universities, all coordinated by NASA’s Human Research Program.

Among the conclusions, the research teams found:

- Scott experienced dramatic shifts in telomere length dynamics, a biomarker that can help evaluate health and potential long-term risks of spaceflight

- 91.3 percent of Scott’s gene expression levels returned to normal or baseline levels within six months of landing back on Earth (note: this does not mean that the rest of his DNA was mutated, as reported in some stories published last year)

- the flu vaccine administered in space worked exactly the same as on Earth

- changes in Scott’s diversity of gut flora in space were no greater than stress-related changes scientists observe on Earth

- proper nutrition and exercise while in space resulted in decreased body mass and increased folic acid, which is vital for making red blood cells, for Scott.

Shorter telomeres mean a higher risk for some age-related health conditions

Bailey said that from her perspective, “the most striking finding” is the elongation of Scott’s telomeres in space. While most of his telomeres returned to near pre-flight averages, he now has more short telomeres than he did prior to the 340-day mission.

Having shorter telomeres puts a person at higher risk for accelerated aging, said Bailey. This also increases the risk for diseases that come along with aging, including cardiovascular disease and some cancers.

“For us Earthlings, it’s pretty similar,” Bailey explained. “We all worry about getting older, and everyone wants to avoid cardiovascular disease and cancer. If we can figure out what’s going on, what’s causing these changes in telomere length, perhaps we could slow it down. That’s something that would be of benefit to everybody.”

Launching a new research mission

Bailey will continue her telomere research with NASA through a new project designed to answer questions about astronaut health and performance on long missions as they journey to the Moon and Mars.

In this integrated One-Year Mission Project, she’ll study 10 astronauts on one-year missions, 10 on six-month missions, and 10 on trips from two to three months at a time. Health data will be compared with people on the ground who are in isolation for those same periods of time.

“We’re trying to determine if it is indeed something specific about space flight that is causing the changes we’ve seen,” she explained.

NASA’s Human Research Program and Space Biology Program funded 25 proposals, all of which will contribute to the space agency’s long-term plans, which include human missions to the Moon and Mars.

Through these studies, NASA aims to address five hazards of human space travel: space radiation, isolation and confinement, distance from Earth, gravity fields (or lack thereof), and hostile or closed environments that pose great risks to the human mind and body in space.

###

Media Contact

Mary Guiden

[email protected]