Credit: Boston Medical Center

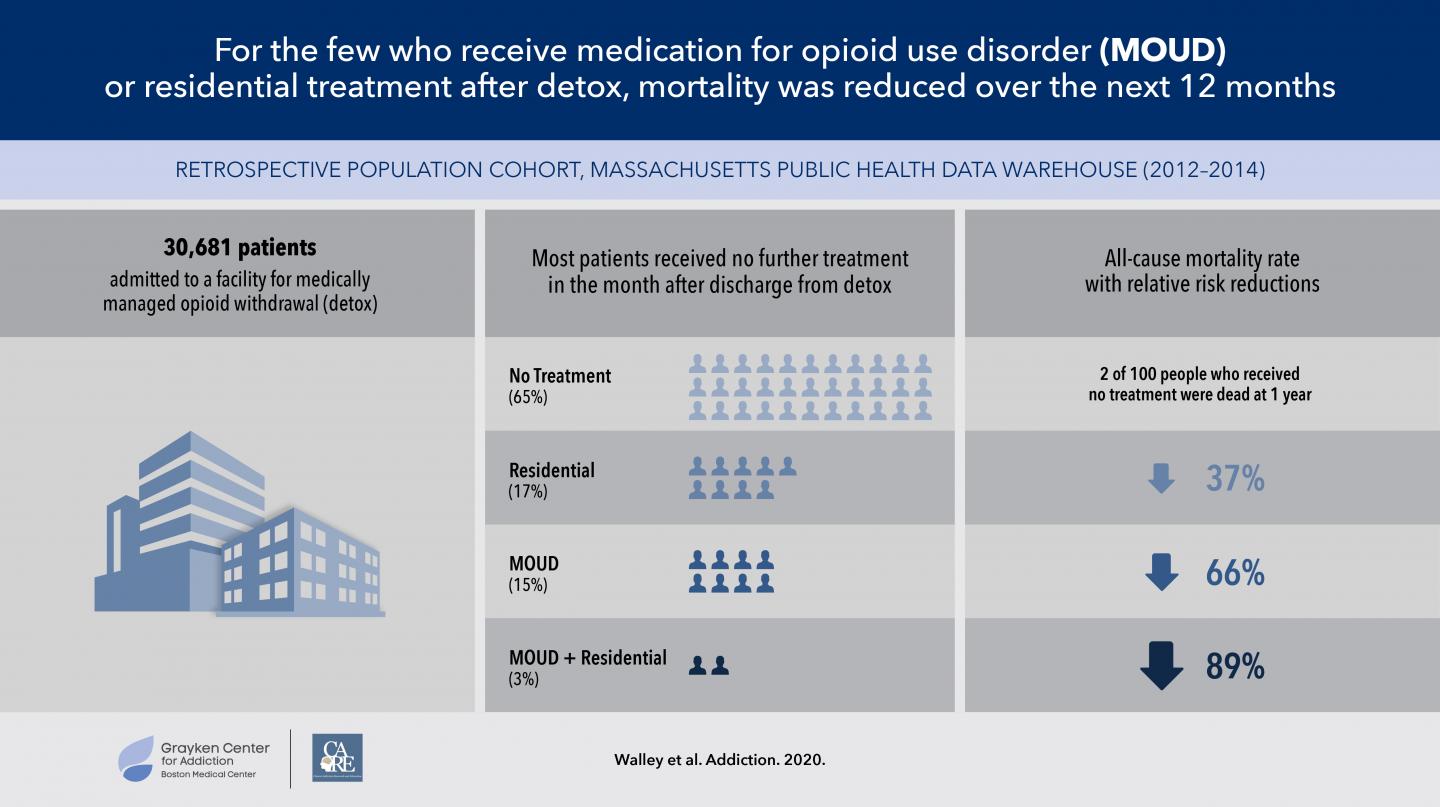

Boston – A new study shows that people with opioid use disorder who enter inpatient medically managed withdrawal treatment (detox) do not usually receive further treatment, including medication for opioid use disorder or additional inpatient treatment. Those who did receive further treatment with medication (methadone, buprenorphine or naltrexone) or residential treatment were more likely to survive to 12 months. Published in Addiction, this study emphasizes the importance of keeping people with opioid use disorder engaged in treatment in order to increase their chances of survival.

Inpatient medically managed withdrawal – detox – is one of the most common ways that people with opioid use disorder (OUD) seek treatment. While people enter detox with the goal of getting better, many do not engage in additional treatment specific to their OUD, including with medication, after discharge. Without ongoing medication for OUD, they leave detox with reduced opioid tolerance, which increases their risk of overdose to rates even higher than when they entered detox. Residential treatment does not typically include medications for OUD during the treatment program.

“Previous studies have shown that FDA-approved medications for opioid use disorder work by reducing opioid use, keeping people in treatment and, for methadone and buprenorphine, decreasing mortality,” said Alexander Walley, MD, MPH, a physician in general internal medicine and researcher with the Grayken Center for Addiction, both at Boston Medical Center. “For this study, we looked specifically at mortality after discharge from detox based on further treatment with medication for opioid use disorder and residential treatment.”

In collaboration with the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, BMC researchers examined individually-linked data sets for persons age 18 and older in Massachusetts with health insurance, focusing on individuals who had gone through detox between January 2012 and December 2014. This timeframe allowed for 12 months of observation prior to and following the first recorded detox. The researchers investigated the 12-month all-cause and opioid-related mortality rates after detox for individuals discharged who: did not get any treatment for OUD; received medication for OUD following discharge; received residential treatment (discontinuing medication); or received residential treatment and medication for OUD.

The data showed that the all-cause mortality rate for those who received no treatment after detox was high, at 2 percent per year, with overdose being the primary cause. Fifteen percent of individuals received medication for OUD in the month after detox, and for those who remained in treatment, their all-cause mortality decreased by 66 percent compared to those who received no treatment. Seventeen percent of individuals received residential treatment, and their all-cause mortality was reduced by 37 percent compared to those who received no treatment. Only three percent of those in the study received both medication for OUD and residential treatment, and their all-cause mortality was reduced by 89 percent compared to those who received no treatment.

“Opioid use disorder is a chronic condition best addressed with ongoing treatment,” said Walley, also an associate professor of medicine at Boston University School of Medicine. “The data from our study shows that medication and residential treatment for opioid use disorder reduce the risk of overdose and death, but these treatments need to continue in order to be effective.”

Of the individuals included in this study, less than half received further treatment after detox, and continued engagement in care in both inpatient and outpatient settings was not typically sustained. The authors note that the combination of medication and residential treatment may be especially effective for those at highest risk.

“It is important to consider the initiation of medication during detox, as well as the expansion of the care system that would enable better collaboration between residential treatment centers and MOUD programs to improve access to medication and increase the number of people remaining in treatment,” added Walley.

###

This study was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (grant award #1UL1TR001430).

About Boston Medical Center

Boston Medical Center is a private, not-for-profit, 514-bed, academic medical center that is the primary teaching affiliate of Boston University School of Medicine. It is the largest and busiest provider of trauma and emergency services in New England. Boston Medical Center offers specialized care for complex health problems and is a leading research institution, receiving more than $97 million in sponsored research funding in fiscal year 2018. It is the 15th largest funding recipient in the U.S. from the National Institutes of Health among independent hospitals. In 1997, BMC founded Boston Medical Center Health Plan, Inc., now one of the top ranked Medicaid MCOs in the country, as a non-profit managed care organization. Boston Medical Center and Boston University School of Medicine are partners in Boston HealthNet – 14 community health centers focused on providing exceptional health care to residents of Boston. For more information, please visit http://www.

Media Contact

Jenny Eriksen Leary

[email protected]

617-638-6841

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.