Researchers at NIPS in Japan show that information flow between two regions in the front of the brain makes it possible for monkeys to correctly interpret social cues

Credit: Taihei Ninomiya

Okazaki, Japan — In baseball, a batter’s reaction when he swings and misses can differ depending on whether they were totally fooled by the pitch or simply missed the change-up they expected. Interpreting these reactions is critical when a pitcher is deciding what the next pitch should be. This type of socially interactive decision-making is the topic of a recent brain study led by Masaki Isoda at the National Institute for Physiological Sciences (NIPS) in Japan. They found that this ability requires a specific connection between two regions in the front of the brain, and that without it, monkeys default to making decisions as if they were playing against an inanimate object.

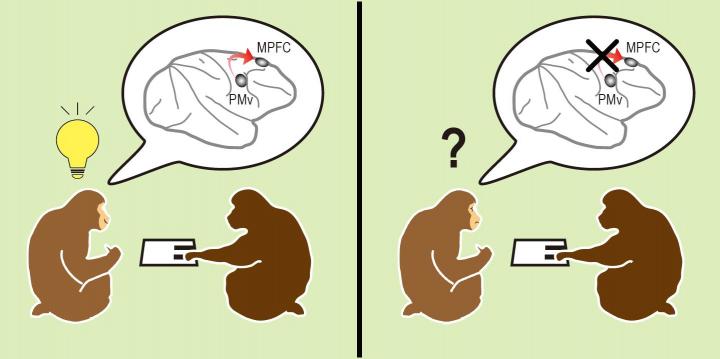

Two regions in the front of the brain–the PMv and the mPFC–contain “self”, “partner”, and “mirror” neurons that signal self-actions, other-actions, or both, respectively. Scientists believe that these types of neurons are what make social qualities such as empathy possible. However, despite years of research, not much is known about how these brain regions work together. The NIPS team set out to find some answers.

They trained monkeys to play a game with a partner in which they pressed buttons to obtain rewards. Sometimes, the rules of the game changed, and the monkeys made mistakes. Sometimes monkeys made mistakes simply because they were careless. “Monkeys continued using the same rule if they thought the other monkey’s mistakes were accidental,” says Masaki Isoda. “But, if they thought the mistakes were because the rules had changed, the monkeys adjusted their thinking and switched rules.” The researchers included three types of partners: real monkeys, recorded monkeys, and inanimate objects.

They found that the proportion of partner cells was much higher in the mPFC than in the PMv, indicating it could be particularly important for understanding what others are thinking. Partner cells in the mPFC were most active and most affected by the PMv when partners were real and least active and least affected when they were inanimate objects. Thus, it seemed possible that the ability of a monkey to recognize social cues depends on mPFC cells getting social information from the PMv.

To test this hypothesis, the researchers used viral vector technology to temporally silence only neurons in the PMv that connect to the mPFC. In this situation, monkeys made many more mistakes after their partners made careless errors, behaving as if every error was because the rules had changed. “This behavior was reminiscent of an autistic monkey who played the same game,” says Taihei Ninomiya. “As difficulty understanding social cues is a hallmark of autism, understanding the role of the PMv-mPFC pathway provides a good direction for future research into autism spectrum disorders.”

###

Media Contact

Masaki Isoda

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.