A highly accurate model of how neurons behave when performing complex movements could aid in the design of robotic limbs which behave more realistically.

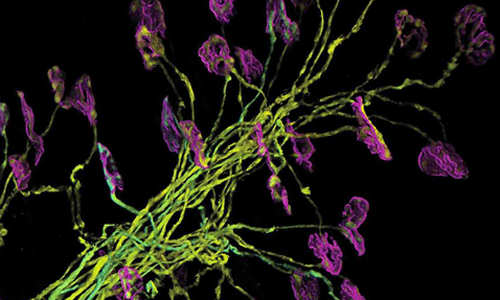

Multiphoton microscopy of mouse motor neurons – Photo Credit: Zeiss Microscopy via flickr

A newly-developed, highly accurate representation of the way in which neurons behave when performing movements such as reaching could not only enhance understanding of the complex dynamics at work in the brain, but aid in the development of robotic limbs which are capable of more complex and natural movements.

Researchers from the University of Cambridge, working in collaboration with the University of Oxford and the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), have developed a new model of a neural network, offering a novel theory of how neurons work together when performing complex movements. The results are published in the 18 June edition of the journal Neuron.

While an action such as reaching for a cup of coffee may seem straightforward, the millions of neurons in the brain’s motor cortex must work together to prepare and execute the movement before the coffee ever reaches our lips. When we reach for the much-needed cup of coffee, the neurons spring into action, sending a series of signals from the brain to the hand. These signals are transmitted across synapses – the junctions between neurons.

Determining exactly how the neurons work together to execute these movements is difficult, however. The new theory was inspired by recent experiments carried out at Stanford University, which had uncovered some key aspects of the signals that neurons emit before, during and after the movement. “There is a remarkable synergy in the activity recorded simultaneously in hundreds of neurons,” said Dr Guillaume Hennequin of the University’s Department of Engineering, who led the research. “In contrast, previous models of cortical circuit dynamics predict a lot of redundancy, and therefore poorly explain what happens in the motor cortex during movements.”

Better models of how neurons behave will not only aid in our understanding of the brain, but could also be used to design prosthetic limbs controlled via electrodes implanted in the brain. “Our theory could provide a more accurate guess of how neurons would want to signal both movement intention and execution to the robotic limb,” said Dr Hennequin.

The behaviour of neurons in the motor cortex can be likened to a mousetrap or a spring-loaded box, in which the springs are waiting to be released and are let go once the lid is opened or the mouse takes the bait. As we plan a movement, the ‘neural springs’ are progressively flexed and compressed. When released, they orchestrate a series of neural activity bursts, all of which takes place in the blink of an eye.

The signals transmitted by the synapses in the motor cortex during complex movements can be either excitatory or inhibitory, which are in essence mirror reflections of each other. The signals cancel each other out for the most part, leaving occasional bursts of activity.

Using control theory, a branch of mathematics well-suited to the study of complex interacting systems such as the brain, the researchers devised a model of neural behaviour which achieves a balance between the excitatory and inhibitory synaptic signals. The model can accurately reproduce a range of multidimensional movement patterns.

The researchers found that neurons in the motor cortex might not be wired together with nearly as much randomness as had been previously thought. “Our model shows that the inhibitory synapses might be tuned to stabilise the dynamics of these brain networks,” said Dr Hennequin. “We think that accurate models like these can really aid in the understanding of the incredibly complex dynamics at work in the human brain.”

Future directions for the research include building a more realistic, ‘closed-loop’ model of movement generation in which feedback from the limbs is actively used by the brain to correct for small errors in movement execution. This will expose the new theory to the more thorough scrutiny of physiological and behavioural validation, potentially leading to a more complete mechanistic understanding of complex movements.

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by University of Cambridge