Skin cells use new molecule to send touch information to the brain. In a study published online today in the journal Nature, a team of Columbia University Medical Center researchers led by Ellen Lumpkin, PhD, associate professor of somatosensory biology, solve an age-old mystery of touch: how cells just beneath the skin surface enable us to feel fine details and textures.

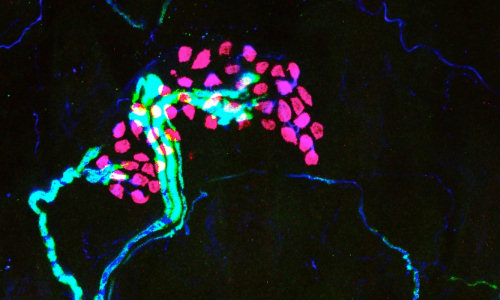

Merkel cells (pink) and neurons (blue)—located just beneath the surface of the skin—create our ability to feel fine details and textures. Photo: Kara Marshall.

Touch is the last frontier of sensory neuroscience. The cells and molecules that initiate vision—rod and cone cells and light-sensitive receptors—have been known since the early 20th century, and the senses of smell, taste, and hearing are increasingly understood. But almost nothing is known about the cells and molecules responsible for initiating our sense of touch.

This study is the first to use optogenetics—a new method that uses light as a signaling system to turn neurons on and off on demand—on skin cells to determine how they function and communicate.

The team showed that skin cells called Merkel cells can sense touch and that they work virtually hand in glove with the skin’s neurons to create what we perceive as fine details and textures.

“These experiments are the first direct proof that Merkel cells can encode touch into neural signals that transmit information to the brain about the objects in the world around us,” Dr. Lumpkin said.

The findings not only describe a key advance in our understanding of touch sensation, but may stimulate research into loss of sensitive-touch perception.

Several conditions—including diabetes and some cancer chemotherapy treatments, as well as normal aging—are known to reduce sensitive touch. Merkel cells begin to disappear in one’s early 20s, at the same time that tactile acuity starts to decline. “No one has tested whether the loss of Merkel cells causes loss of function with aging—it could be a coincidence—but it’s a question we’re interested in pursuing,” Dr. Lumpkin said.

In the future, these findings could inform the design of new “smart” prosthetics that restore touch sensation to limb amputees, as well as introduce new targets for treating skin diseases such as chronic itch.

The study was published in conjunction with a second study by the team done in collaboration with the Scripps Research Institute. The companion study identifies a touch-activated molecule in skin cells, a gene called Piezo2, whose discovery has the potential to significantly advance the field of touch perception.

“The new findings should open up the field of skin biology and reveal how sensations are initiated,” Dr. Lumpkin said. Other types of skin cells may also play a role in sensations of touch, as well as less pleasurable skin sensations, such as itch. The same optogenetics techniques that Dr. Lumpkin’s team applied to Merkel cells can now be applied to other skin cells to answer these questions.

“It’s an exciting time in our field because there are still big questions to answer, and the tools of modern neuroscience give us a way to tackle them,” she said.

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by Columbia University.