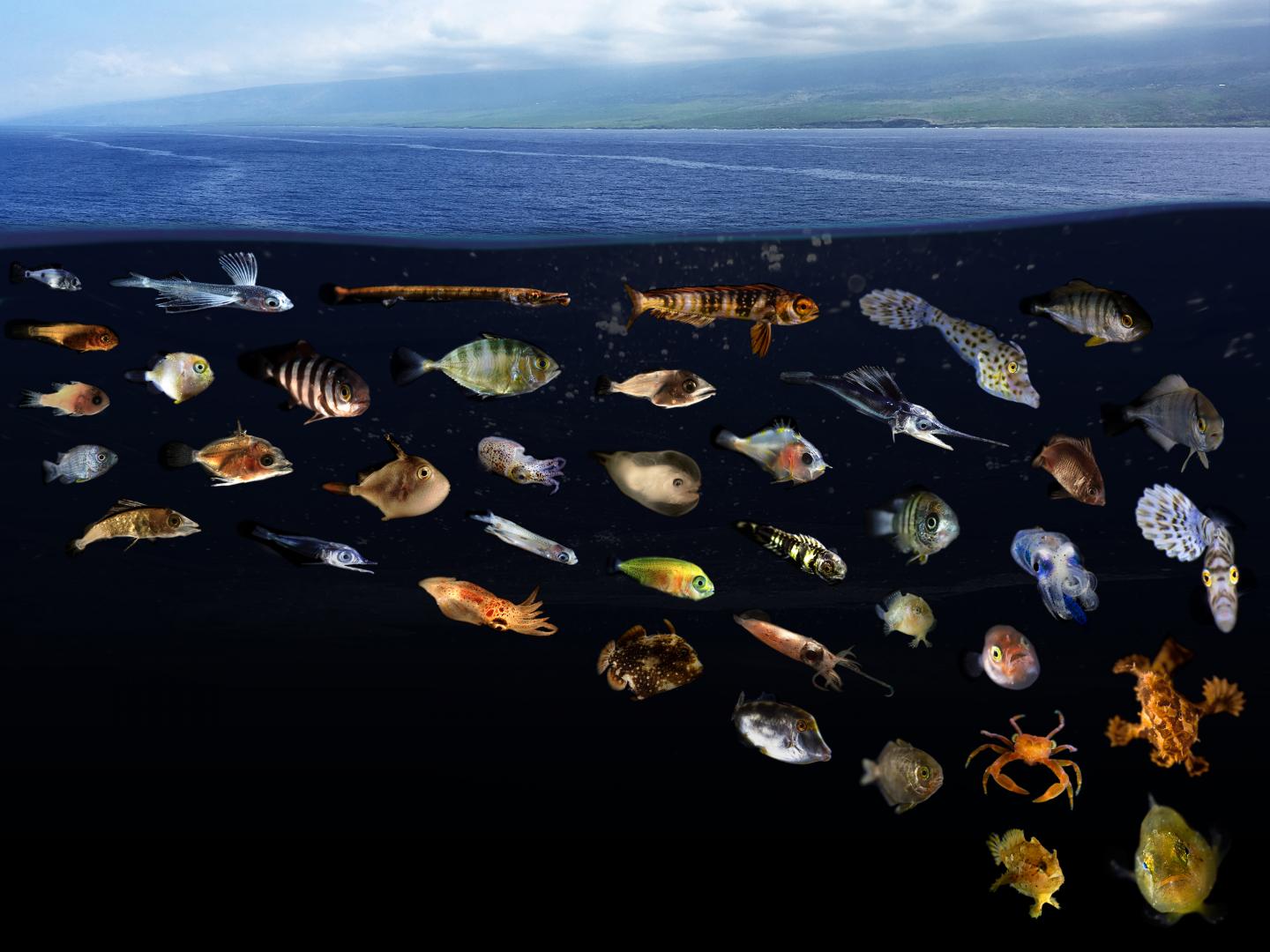

Ocean surface slicks are pelagic nurseries for diverse fishes

Credit: Credit: Larval photos: Jonathan Whitney (NOAA Fisheries), Slick photo: Joey Lecky (NOAA Fisheries).

To survive the open ocean, tiny fish larvae, freshly hatched from eggs, must find food, avoid predators, and navigate ocean currents to their adult habitats. But what the larvae of most marine species experience during these great ocean odysseys has long been a mystery, until now.

A team of scientists from NOAA’s Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, the University of Hawai’i (UH) at Mānoa, Arizona State University and elsewhere have discovered that a diverse array of marine animals find refuge in so-called ‘surface slicks’ in Hawai’i. These ocean features create a superhighway of nursery habitat for more than 100 species of commercially and ecologically important fishes, such as mahi-mahi, jacks, and billfish. Their findings were published today in the journal Scientific Reports.

Surface slicks are meandering lines of smooth surface water formed by the convergence of ocean currents, tides, and variations in the seafloor and have long been recognized as an important part of the seascape. The traditional Hawaiian mele (song) Kona Kai `?pua describes slicks as Ke kai ma`oki`oki, or “the streaked sea” in the peaceful seas of Kona. Despite this historical knowledge and scientists’ belief that slicks are important for fish, the tiny marine life that slicks contain has remained elusive.

To unravel the slicks’ secrets, the research team conducted more than 130 plankton net tows inside the surface slicks and surrounding waters along the leeward coast of Hawai’i Island, while studying ocean properties. In these areas, they searched for larvae and other plankton that live close to the surface. They then combined those in-water surveys with a new technique to remotely sense slick footprints using satellites.

A DIVERSE MARINE NURSERY

Though the slicks only covered around 8% of the ocean surface in the 380-square-mile-study area, they contained an astounding 39% of the study area’s surface-dwelling larval fish; more than 25% of its zooplankton, which the larval fish eat; and 75% of its floating organic debris such as feathers and leaves.

Larval fish densities in surface slicks off West Hawai?i were, on average, over 7 times higher than densities in the surrounding waters.

The study showed that surface slicks function as a nursery habitat for marine larvae of at least 112 species of commercially and ecologically important fishes, as well as many other animals. These include coral reef fishes, such as jacks, triggerfish and goatfish; pelagic predators, for example mahi-mahi; deep-water fishes, such as lanternfish; and various invertebrates, such as snails, crabs, and shrimp.

The remarkable diversity of fishes found in slick nurseries represents nearly 10% of all fish species recorded in Hawai?i. The total number of taxa in the slicks was twice that found in the surrounding surface waters, and many fish taxa were between 10 and 100 times more abundant in slicks.

“We were shocked to find larvae of so many species, and even entire families of fishes, that were only found in surface slicks,” said lead author Dr. Jonathan Whitney, marine ecologist at NOAA, former postdoctoral fellow at the Joint Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research (JIMAR) in UH Mānoa’s School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST). “This suggests they are dependent on these essential habitats.”

AN INTERCONNECTED SUPERHIGHWAY

“These ‘bioslicks’ form an interconnected superhighway of rich nursery habitat that accumulate and attract tons of young fishes, along with dense concentrations of food and shelter,” said Whitney. “The fact that surface slicks host such a large proportion of larvae, along with the resources they need to survive, tells us they are critical for the replenishment of adult fish populations.”

In addition to providing crucial nursing habitat for various species and helping maintain healthy and resilient coral reefs, slicks create foraging hotspots for larval fish predators and form a bridge between coral reef and pelagic ecosystems.

What’s more, the slicks host larvae and juvenile stages of many forage fishes like flying fishes that are critical to pelagic food webs.

“These hotspots provide more food at the base of the food chain that amplifies energy up to top predators,” said study co-author Dr. Jamison Gove, a research oceanographer for NOAA. “This ultimately enhances fisheries and ecosystem productivity.”

CONCENTRATING DEBRIS

While slicks may seem like havens for all tiny marine animals, there’s a hidden hazard lurking in these ocean oases: plastic debris. Within the study area, 95% of the plastic debris collected into slicks, compared with 75% of the floating organic debris. Larvae may get some shelter from plastic debris, but it comes at the cost of chemical exposure and incidental ingestion.

“Until we stop plastics from entering the ocean,” Whitney said, “the accumulation of hazardous plastic debris in these nursery habitats remains a serious threat to the biodiversity hosted here.”

A BROAD IMPACT

In certain areas, slicks can be dominant surface features, and the new research shows these conspicuous phenomena hold more ecological value than meets the eye.

“Our work illustrates how these oceanic features (and animals’ behavioral attraction to them) impact the entire surface community, with implications for the replenishment of adults that are important to humans for fisheries, recreation, and other ecosystem services,” said Dr. Margaret McManus, co-author, Professor and Chair of the Department of Oceanography at UH Mānoa. “These findings will have a broad impact, changing the way we think about oceanic features as pelagic nurseries for ocean fishes and invertebrates.”

###

Media Contact

Marcie Grabowski

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.