University of Cincinnati researchers examined weather factors that contribute to devastating western wildfires; they found that wildfires were most likely on hot days

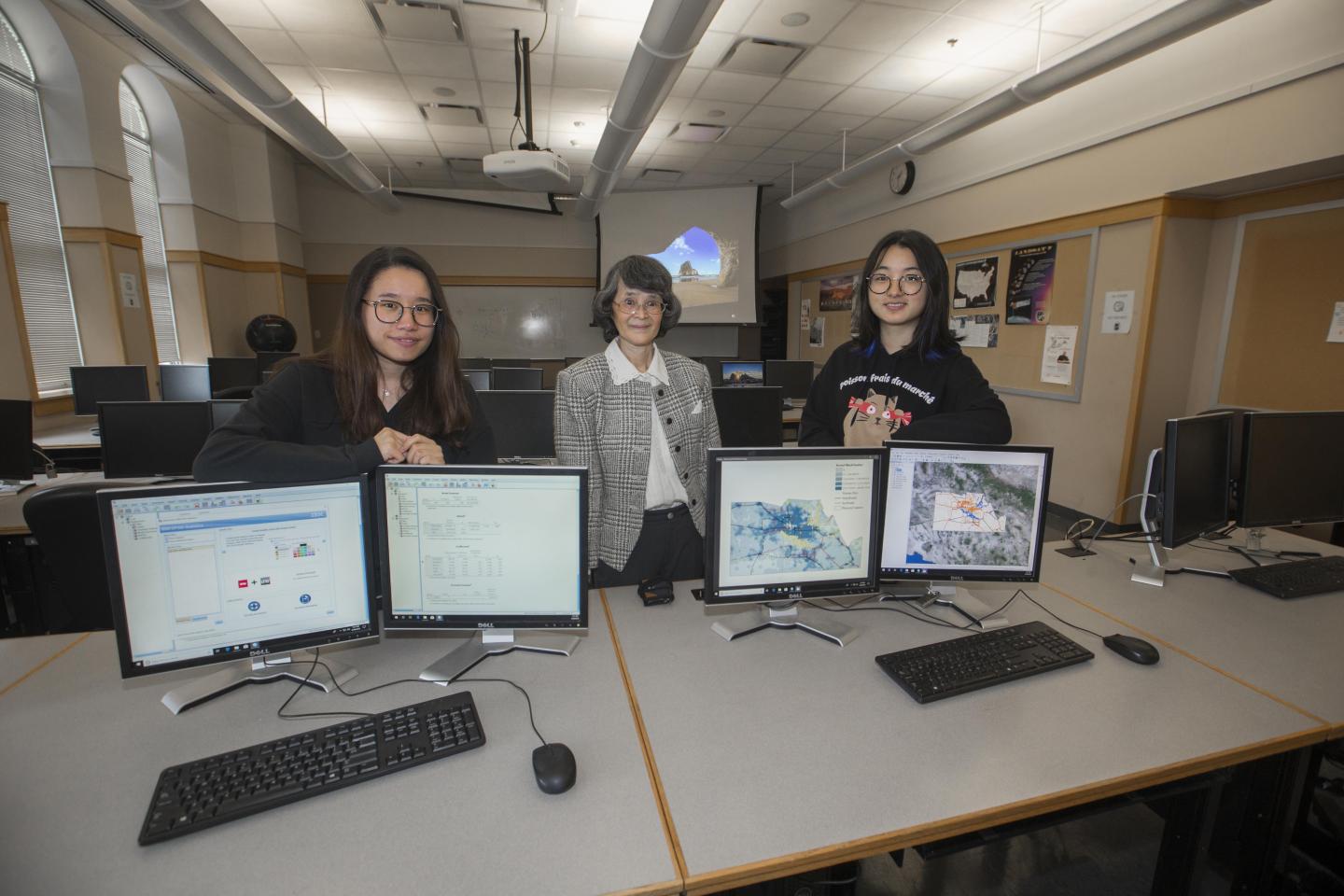

Credit: Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

One of the best predictors of western wildfires could be how hot it’s been, according to a new geography study by the University of Cincinnati.

Geography professor Susanna Tong and her students studied a variety of weather, microclimate and ground conditions in historic fires around Phoenix, Arizona, and Las Vegas, Nevada, to determine which might be the most important in predicting the risk of wildfire.

They found that temperature was a better predictor than humidity, rainfall, moisture content of the vegetation and soil and other factors. They presented their findings this month at the American Association of Geographers conference in Washington, D.C.

“We examined a long list of data. The results show that the maximum temperatures had the highest correlation with fires,” UC student Diqi Zeng said. “That makes sense because if you have high temperatures, a fire is easier to ignite.”

California last year witnessed the deadliest wildfire of the past century in the United States — a blaze that killed at least 88 people and caused an estimated $9 billion in damage, according to state insurers. Four of the state’s five biggest wildfires on record have broken out since 2012.

Identifying the risk factors is an important step in preventing future blazes, Tong said.

UC student researcher Shitian Wan said she wanted to study wildfire after watching news coverage of the devastating 2018 Camp Fire in California, which her study referenced.

“The recent California wildfire, which is the deadliest and most destructive wildfire on record, showed clearly the devastating consequences. A better understanding of wildfire incidents is therefore crucial in fire prevention and future planning,” their study said.

Wan said she hopes research like hers will make a difference to people living in areas of high fire risk.

“What I’m trying to do is investigate the causal factors to create a risk map to examine where wildfires are most likely so people will be more informed,” Wan said.

UC students such as Yuhe Gao used geospatial and statistical tools to study the problem. The researchers found that the lack thereof even months prior to an event was a contributing factor.

“We found that precipitation even two months earlier can influence wildfires,” UC student Wan said. “So if it rains a lot even two months ago, wildfires will be less likely.”

Likewise, the researchers found that wildfires were more likely to start in woodlands than pastures, possibly because more of those pastures are owned by ranchers who plan for fire by removing dead timber or brush and adding fire breaks.

The researchers studied vegetation cover and type, moisture level, proximity to roads and population centers and historic weather data. Fires can be more harmful to vegetation in semiarid Arizona and Nevada than parts of California that get far more rainfall, Tong said.

“The plants around Phoenix and Las Vegas need a long regeneration time. Because of the rainfall in northern California the environment recovers from a fire relatively quickly,” she said.

Wildfires can be especially destructive in the Southwest because homes are sometimes built near or surrounded by natural areas. Surrounding trees and scrub can provide fuel for a devastating wildfire.

“They’re infringing into the urban-wildland interface, so wildfire is of particular concern to them,” Tong said. “That’s where suburbia meets the woods. So property loss can be substantial if there is a wildfire.”

Finding long-term solutions to reduce fire risk will require a coordinated effort, Tong said.

Planning boards can encourage smarter zoning practices in fire-prone areas. NASA can use remote sensing to keep track of ground or vegetation moisture content.

Climatologists can build forecasts that help forestry officials plan for fire season and forestry officials can remove dead timber to minimize fires that do break out.

“It’s a complex issue. Maybe better zoning regulations, better evacuation strategies, better forecasting and better monitoring,” Tong said. “I think all of those are important.”

Students like Zeng said these geography studies are especially valuable now.

“Because of global warming, wildfires are only expected to get worse,” Zeng said. “We need to better understand what causes these fires and how to control them.”

###

Media Contact

Michael Miller

[email protected]

Original Source

http://uc.