Researchers find that simple DNA-peptide interactions create a surprising diversity of compartmentalised higher-ordered phase behaviours, suggesting that these polymers’ primordial interactions helped create modern complex biological structures.

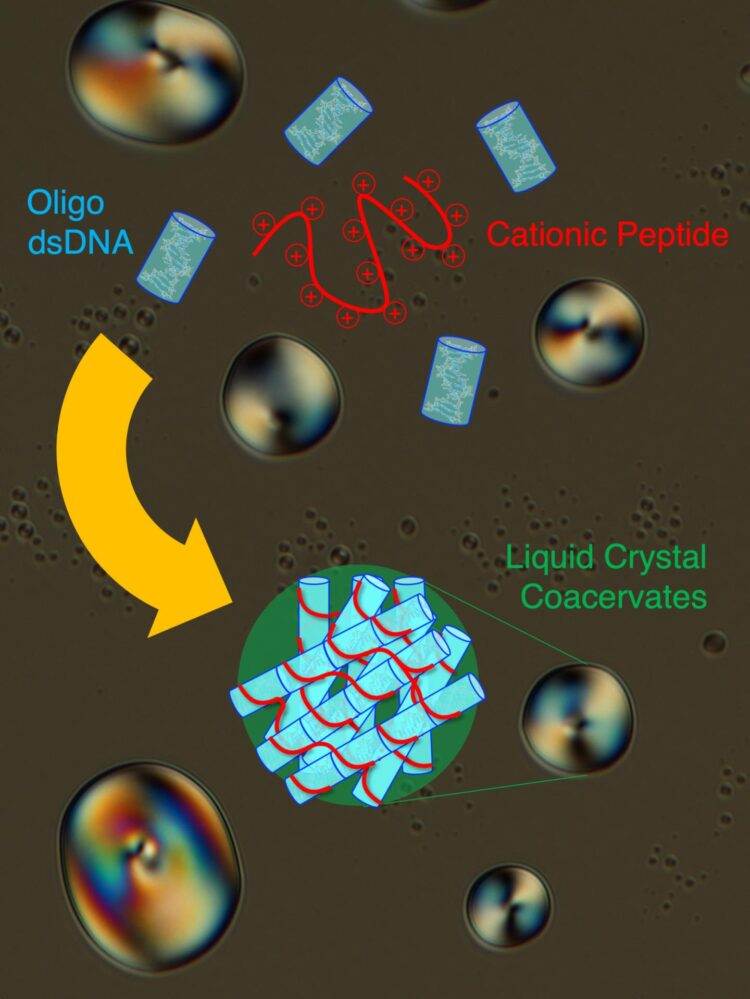

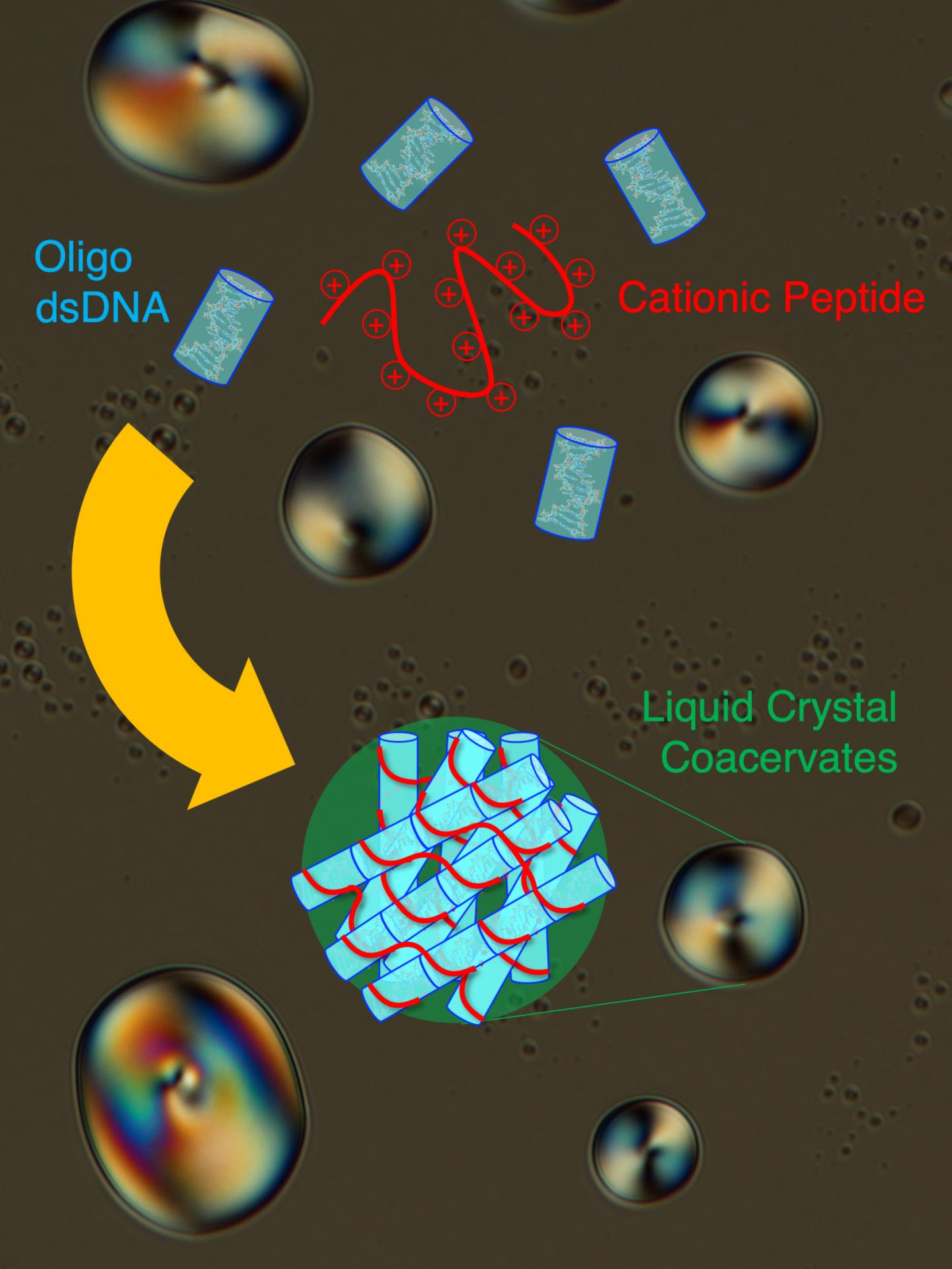

Credit: Tommaso P Fraccia

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA)-protein interactions are extremely important in biology. For example, each human cell contains about 2 meters worth of DNA, but this is packaged into a space about one million times smaller. The information in this DNA allows the cell to copy itself. This extreme packaging is mainly accomplished in cells by wrapping the DNA around proteins. Thus, how DNA and proteins interact is of extreme interest to scientists trying to understand how biology organises itself. New research by scientists at the Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI) at Tokyo Institute of Technology and the Institut Pierre-Gilles de Gennes, ESPCI Paris, Université PSL suggests that the interactions of DNA and proteins have deep-seated propensities to form higher-ordered structures such as those which allow the extreme packaging of DNA in cells.

Modern living cells are principally composed of a few classes of large molecules. DNA gets the lion’s share of attention as it is the repository of the information cells use to build themselves generation after generation. This information-rich DNA is normally present as a double-stranded caduceus of two polymers wrapped around each other, with much of what makes the information DNA contains obscured to the external environment because the information-bearing parts of the molecules are engaged with their complementary strand. When DNA is copied into ribonucleic acid (RNA), its strands are pulled apart to allow its more complex surfaces to interact, which enables it to be copied into single-stranded RNA polymers. These RNA polymers are finally read out by biological processes into proteins, which are polymers of a variety of amino acids with extremely complicated surface properties. Thus, DNA and RNA are somewhat predictable in terms of their chemical behaviour as polymers, while proteins are not.

Polymeric molecules, those composed or repeated types of subunits, can display complex behaviours when mixed with other chemicals, especially when dissolved in a solvent like water. Chemists have developed a complex set of terms for how compounds behave when they are mixed. For example, the proteins in cow’s milk are considered a colloidal (or homogeneous noncrystalline suspended mixture which does not settle and cannot be separated by physical means) suspension in water. When lemon juice is added to milk, the suspended proteins reorganise themselves to produce the visible self-organisation of curds, which do separate into a new phase. There are other types of this phenomenon chemists have discovered over the years, for example, liquid crystals (LC). LCs are formed when a molecules have an elongated shape or the tendency to make linear aggregates (like stacks of molecules one on top of each other): the resulting material presents a mixture of the properties of a crystal and a liquid: the material thus has a certain degree of order like a solid (for example, parallel orientation of the molecules) but still retains its fluidity (molecules can easily slip on and by each other). We all experience liquid crystals in the various screens we interact with every day “LCDs,” or liquid crystal displays, which use these variable properties to make the images we see on our device screens. In their work, Fraccia and Jia, showed that double-stranded DNA and peptides can generate many different LC phases in a very peculiar way: the LCs actually form in membraneless droplets, called coacervates, where DNA and peptides are spontaneously co-assembled and ordered. This process brings DNA and peptides to very high concentrations, comparable to that of a cell’s nucleus, which is 100-1000 times greater of that of the very diluted initial solution (which is the maximum concentration that can likely be achieved on early Earth). Thus, such spontaneous behaviour can in principle favour the formation of the first cell-like structures on early Earth, which would take advantage of the ordered, but fluid, LC matrix in order to gain stability and functionality, and to favour the growth and the evolution of primitive biomolecules.

The cut-off between when these higher-order properties begin to present themselves is not always clear cut. When molecules interact at the molecular level, they often “self-organise.” One can think of the process of adding sand to a sandpile: as one sprinkles more and more sand to a pile, it tends to form a “low energy” final state – a pile. Though the addition of sand grains may cause some new structures to form locally, at some point, the addition of one more grain causes a landslide in the pile which reinforces the conical shape of the pile.

Though we all benefit from the existence of these phenomena, the scientific community may be missing important aspects of the implications of this type of self-organisation, Jia and Fraccia argue. The combination of these collective material self-organising effects may be relevant at many scales of biology and may be important for biomolecular structure transitions in cell physiology and disease. In particular, the researchers discovered that various liquid crystalline structures could be accessed continuously simply by changes in environmental conditions, even as simple as changes in salinity or temperature; given the numerous unexplored conditions, this work suggests many more novel self-organised LC mesophases with potential biological function could be discovered in the near future.

This new understanding of biopolymeric self-organisation may also be important for understanding how life self-organised to become living in the first place. Understanding how primitive collections of molecules could have structured themselves into collectively behaving aggregates is a significant avenue of future research.

“When the general public hears about liquid crystals, they might think of TV screens and engineering applications. However, very few would immediately think of basic science. Most researchers would not even make the connection between LCs and the origins of life. We hope this work will help increase the public’s understanding of LCs in the context of the origins of life,” says co-author Jia.

Finally, this work may also be relevant to disease. For example, recent discoveries regarding diseases including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Huntington’s Disease, and ALS (Lou Gehrig’s Disease) have pointed to intracellular phase transitions and separation leading to membraneless droplets as potential major causes.

The researchers noted that though their work was heavily impacted by the pandemic, they did their best to keep working under the global shutdowns and travel restrictions.

###

Reference

Tommaso P. Fraccia1* & Tony Z. Jia2,3, Liquid Crystal Coacervates Composed of Short Double-Stranded DNA and Cationic Peptides, ACS Nano, DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.0c05083

1. Institut Pierre-Gilles de Gennes, Chimie Biologie Innovation, ESPCI Paris, CNRS, PSL Research University, 75005 Paris, France

2. Earth-Life Science Institute, Tokyo Institute of Technology, 2-12-1-IE-1 Ookayama, Meguro-ku, Tokyo 152-8550, Japan

3. Blue Marble Space Institute of Science, 1001 Fourth Ave., Suite 3201, Seattle, Washington 98154, United States

More information

Tokyo Institute of Technology (Tokyo Tech) stands at the forefront of research and higher education as the leading university for science and technology in Japan. Tokyo Tech researchers excel in fields ranging from materials science to biology, computer science, and physics. Founded in 1881, Tokyo Tech hosts over 10,000 undergraduate and graduate students per year, who develop into scientific leaders and some of the most sought-after engineers in industry. Embodying the Japanese philosophy of “monotsukuri,” meaning “technical ingenuity and innovation,” the Tokyo Tech community strives to contribute to society through high-impact research.

The Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI) is one of Japan’s ambitious World Premiere International research centers, whose aim is to achieve progress in broadly inter-disciplinary scientific areas by inspiring the world’s greatest minds to come to Japan and collaborate on the most challenging scientific problems. ELSI’s primary aim is to address the origin and co-evolution of the Earth and life.

The World Premier International Research Center Initiative (WPI) was launched in 2007 by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) to help build globally visible research centers in Japan. These institutes promote high research standards and outstanding research environments that attract frontline researchers from around the world. These centers are highly autonomous, allowing them to revolutionise conventional modes of research operation and administration in Japan.

Media Contact

Thilina Heenatigala

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.