Human lung organoids may help scientists learn more about lung diseases, test new drugs

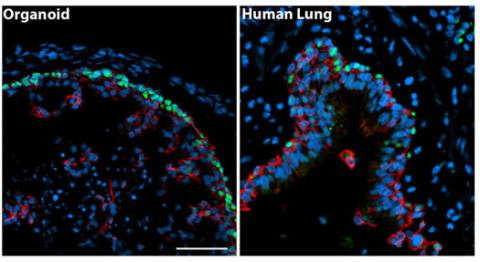

The panel on the left is a cross section through an organoid, viewed through a microscope and stained to visualize the lung tissue. Lung tissue in organoids is organized in a similar manner to the adult lung, shown in the right panel.

Previous research has focused on deriving lung tissue from flat cell systems or growing cells onto scaffolds made from donated organs. In a study published in the online journal eLife the multi-institution team defined the system for generating the self-organizing human lung organoids, 3D structures that mimic the structure and complexity of human lungs.

“These mini lungs can mimic the responses of real tissues and will be a good model to study how organs form, change with disease, and how they might respond to new drugs,” says senior study author Jason R. Spence, Ph.D., assistant professor of internal medicine and cell and developmental biology at the University of Michigan Medical School.

The scientists succeeded in growing structures resembling both the large airways known as bronchi and small lung sacs called alveoli.

Since the mini lung structures were developed in a dish, they lack several components of the human lung, including blood vessels, which are a critical component of gas exchange during breathing.

Still, the organoids may serve as a discovery tool for researchers as they churn basic science ideas into clinical innovations. A practical solution lies in using the 3-D structures as a next step from, or complement to, animal research.

Cell behavior has traditionally been studied in the lab in 2-D situations where cells are grown in thin layers on cell-culture dishes. But most cells in the body exist in a three-dimensional environment as part of complex tissues and organs.

Researchers have been attempting to re-create these environments in the lab, successfully generating organoids that serve as models of the stomach, brain, liver and human intestine.

The advantage of growing 3-D structures of lung tissue, Spence says, is that their organization bears greater similarity to the human lung.

How to make a human lung in a dish

To make these lung organoids, researchers at the U-M’s Spence Lab and colleagues from the University of California, San Francisco; Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center; Seattle Children’s Hospital and University of Washington, Seattle manipulated several of the signaling pathways that control the formation of organs.

First, stem cells – the body’s master cells — were instructed to form a type of tissue called endoderm, which is found in early embryos and gives rise to the lung, liver and several other internal organs.

Scientists activated two important development pathways that are known to make endoderm form three-dimensional tissue. By inhibiting two other key development pathways at the same time, the endoderm became tissue that resembles the early lung found in embryos.

In the lab, this early lung-like tissue spontaneously formed three-dimensional spherical structures as it developed. The next challenge was to make these structures expand and develop into lung tissue. To do this, the team exposed the cells to additional proteins that are involved in lung development.

The resulting lung organoids survived in the lab for over 100 days.

“We expected different cells types to form, but their organization into structures resembling human airways was a very exciting result,” says lead study author Briana Dye, a graduate student in the U-M Department of Cell and Developmental Biology.

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by University of Michigan Health System.