Museum collections reveal the history of mic

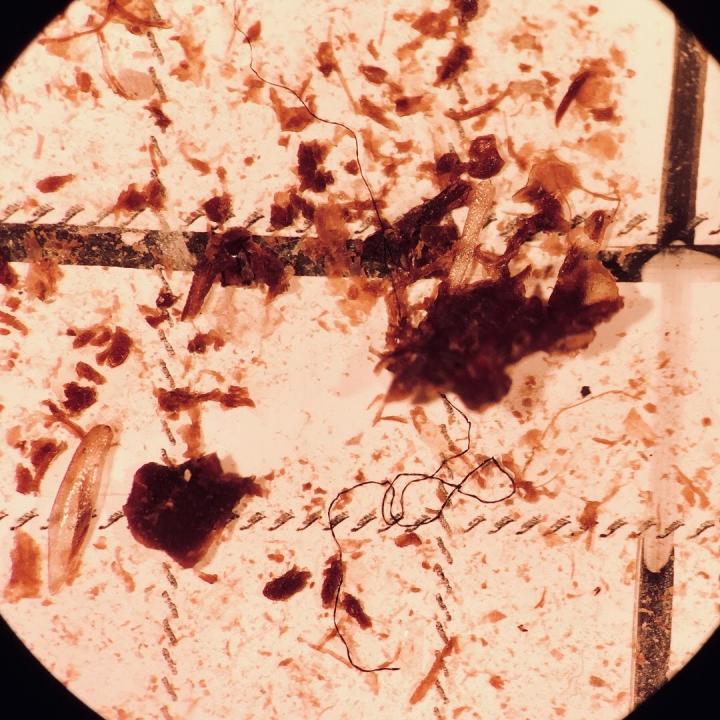

Credit: Loren Hou

Forget diamonds–plastic is forever. It takes decades, or even centuries, for plastic to break down, and nearly every piece of plastic ever made still exists in some form today. We’ve known for a while that big pieces of plastic can harm wildlife–think of seabirds stuck in plastic six-pack rings–but in more recent years, scientists have discovered microscopic bits of plastic in the water, soil, and even the atmosphere. To learn how these microplastics have built up over the past century, researchers examined the guts of freshwater fish preserved in museum collections; they found that fish have been swallowing microplastics since the 1950s and that the concentration of microplastics in their guts has increased over time.

“For the last 10 or 15 years it’s kind of been in the public consciousness that there’s a problem with plastic in the water. But really, organisms have probably been exposed to plastic litter since plastic was invented, and we don’t know what that historical context looks like,” says Tim Hoellein, an associate professor of biology at Loyola University Chicago and the corresponding author of a new study in Ecological Applications. “Looking at museum specimens is essentially a way we can go back in time.”

Caleb McMahan, an ichthyologist at the Field Museum, cares for some two million fish specimens, most of which are preserved in alcohol and stored in jars in the museum’s underground Collections Resource Center. These specimens are more than just dead fish, though–they’re a snapshot of life on Earth. “We can never go back to that time period, in that place,” says McMahan, a co-author of the paper.

Hoellein and his graduate student Loren Hou were interested in examining the buildup of microplastics in freshwater fish from the Chicagoland region. They reached out to McMahan, who helped identify four common fish species that the museum had chronological records of dating back to 1900: largemouth bass, channel catfish, sand shiners, and round gobies. Specimens from the Illinois Natural History Survey and University of Tennessee also filled in sampling gaps.

“We would take these jars full of fish and find specimens that were sort of average, not the biggest or the smallest, and then we used scalpels and tweezers to dissect out the digestive tracts,” says Hou, the paper’s lead author. “We tried to get at least five specimens per decade.”

To actually find the plastic in the fishes’ guts, Hou treated the digestive tracts with hydrogen peroxide. “It bubbles and fizzes and breaks up all the organic matter, but plastic is resistant to the process,” she explains.

The plastic left behind is too tiny to see with the naked eye, though: “It just looks like a yellow stain, you don’t see it until you put it under the microscope,” says Hou. Under the magnification, though, it’s easier to identify. “We look at the shape of these little pieces. If the edges are frayed, it’s often organic material, but if it’s really smooth, then it’s most likely microplastic.” To confirm the identity of these microplastics and determine where they came from, Hou and Hoellein worked with collaborators at the University of Toronto to examine the samples using Raman spectroscopy, a technique that uses light to analyze the chemical signature of a sample.

The researchers found that the amount of microplastics present in the fishes’ guts rose dramatically over time as more plastic was manufactured and built up in the ecosystem. There were no plastic particles before mid-century, but when plastic manufacturing was industrialized in the 1950s, the concentrations skyrocketed.

“We found that the load of microplastics in the guts of these fishes have basically gone up with the levels of plastic production,” says McMahan. “It’s the same pattern of what they’re finding in marine sediments, it follows the general trend that plastic is everywhere.”

The analysis of the microplastics revealed an insidious form of pollution: fabrics. “Microplastics can come from larger objects being fragmented, but they’re often from clothing,” says Hou–whenever you wash a pair of leggings or a polyester shirt, tiny little threads break off and get flushed into the water supply.

“It’s plastic on your back, and that’s just not the way that we’ve been thinking about it,” says Hoellein. “So even just thinking about it is a step forward in addressing our purchases and our responsibility.”

It’s not clear how ingesting these microplastics affected the fish in this study, but it’s probably not great. “When you look at the effects of microplastic ingestion, especially long term effects, for organisms such as fish, it causes digestive tract changes, and it also causes increased stress in these organisms,” says Hou.

While the findings are stark–McMahan described one of the paper’s graphs showing the sharp rise in microplastics as “alarming”–the researchers hope it will serve as a wake-up call. “The entire purpose of our work is to contribute to solutions,” says Hoellein. “We have some evidence that public education and policies can change our relationship to plastic. It’s not just bad news, there’s an application that I think should give everyone a collective reason for hope.”

The researchers say the study also highlights the importance of natural history collections in museums. “Loren and I both love the Field Museum but don’t always think about it in terms of its day-to-day scientific operations,” says Hoellein. “It’s an incredible resource of the natural world, not just as it exists now but as it existed in the past. It’s fun for me to think of the museum collection sort of like the voice of those long dead organisms that are still telling us something about the state of the world today.”

“You can’t do this kind of work without these collections,” says McMahan. “We need older specimens, we need the recent ones, and we’re going to need what we collect in the next 100 years.”

###

Media Contact

Kate Golembiewski

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.