Credit: Harris, GH, et al. JAMA Network Open, 2021

PITTSBURGH, March 19, 2021 – A University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine-led survey of dozens of surge capacity managers at hospitals nationwide captures the U.S. health care system’s pandemic preparedness status in the months before the first COVID-19 cases were identified in China.

Published today in the journal JAMA Network Open, the investigation details the strain experienced by U.S. hospitals during the 2017-18 influenza season, which was marked by severe illness and the highest infectious disease-related hospitalization rates in at least a decade. At the time, pandemic planning within hospitals was not reported as being a high priority.

“The timing for our survey couldn’t have been better–ultimately it serves as a pre-COVID-19 time capsule of our preparedness to accommodate surges in patients needing hospitalization for acute illness,” said senior author David Wallace, M.D., M.P.H., associate professor in Pitt’s departments of Critical Care Medicine and Emergency Medicine. “It was surprising to hear very detailed stories of the strain hospitals were under during the 2017-18 flu season, and yet have no pandemic planning come out of it.”

The 2017-18 flu season was associated with more than 27.7 million medical visits, nearly a million hospitalizations and almost 80,000 deaths, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That is more than double the deaths in a typical flu season and the highest hospitalization rate since seasonal influenza surveillance was instituted in 2005.

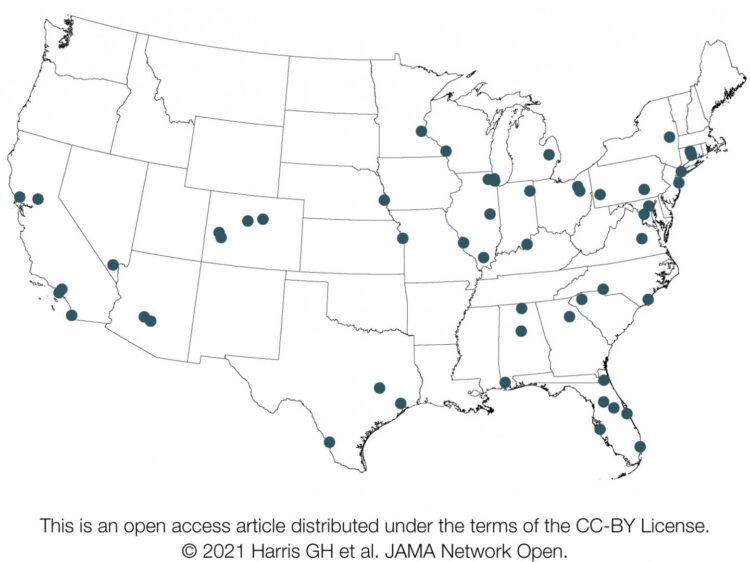

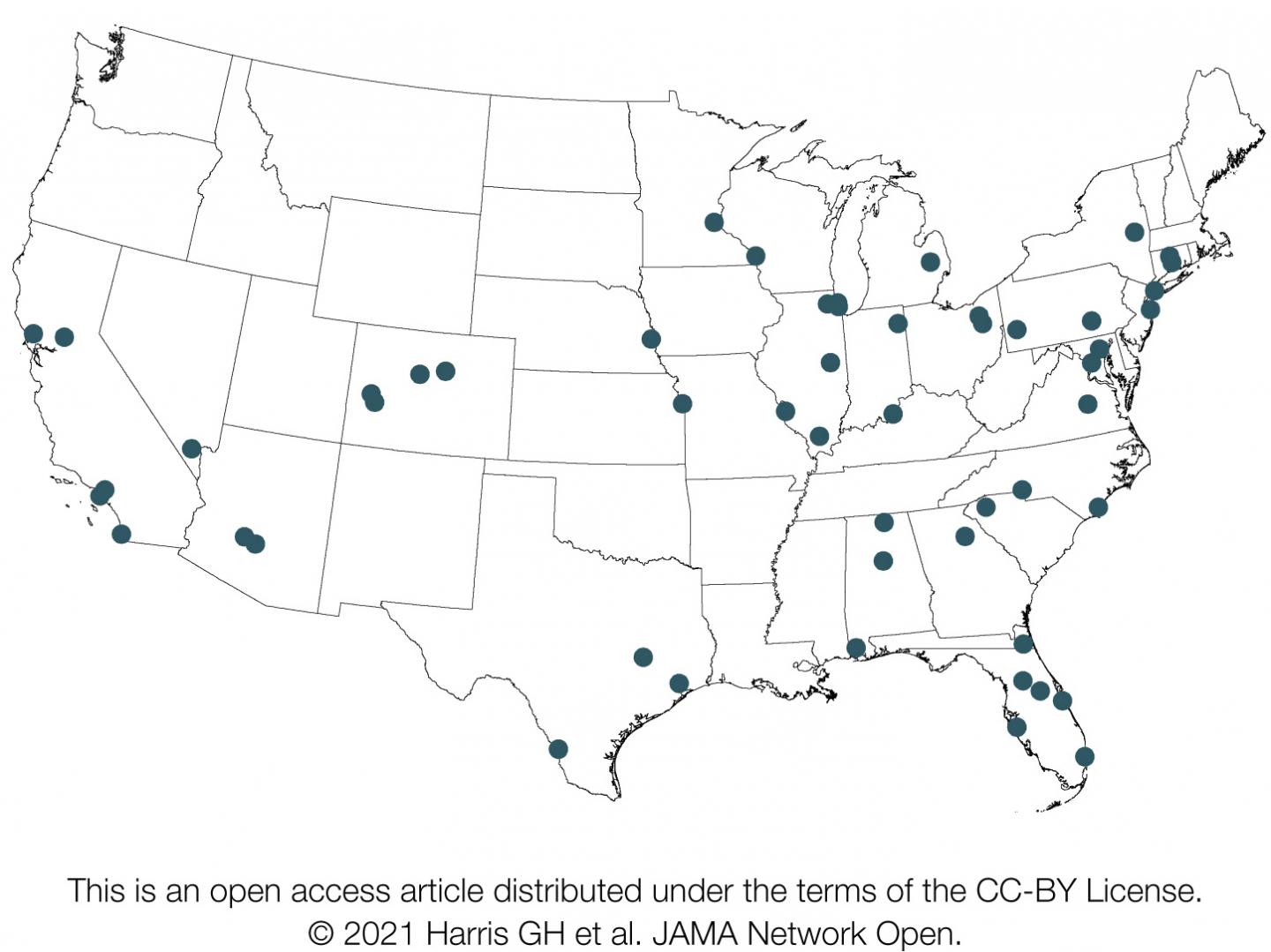

Wallace and his team–which included specialists in health policy, medical anthropology and infectious diseases–interviewed surge capacity managers at a random sampling of 53 hospitals across the U.S. starting in April 2018, at the tail end of the flu season. Using a structured survey, they recorded detailed interviews about everything from ICU bed capacity and staffing ratios to the perceived effect of strain on quality of patient care and staff well-being.

All of those surveyed reported experiencing hospital strain during the 2017-18 flu season. Strain was generally described as the result of high patient occupancy causing demand to outstrip the supply of resources–in fact or in perception.

The “4 S’s”–staff, stuff, space and systems–were reported as the widespread challenges that surge capacity managers consistently faced in continuing health care operations during the flu season. Staff was a particular concern, due to fatigue or staff being out sick with flu or caring for ill family.

“This demonstrates that the perceptions of strain on staffing, patient care and capacity that we have seen during the COVID-19 pandemic were already present with prior epidemics,” said lead author Gavin Harris, M.D., an assistant professor in the Emory University School of Medicine, who did this research while at Pitt. “Less than two years before COVID-19 took off in the U.S., we were experiencing a preview of the strain that a fast-spreading, severe respiratory infection places on our health system.”

In fall 2013–four years before this challenging flu season–the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response produced the Interim Healthcare Coalition Checklist for Pandemic Planning report, which identified eight categories hospitals should address when planning for crises, specifically surges in acute care needs. None of the survey participants commented on all eight categories, nor did any specifically report using the checklist.

“Hospitals have a tendency to deal with what’s right in front of them, the present,” Wallace said. “In doing that, we must also learn when certain levers–like a pandemic preparedness checklist–must be pulled. That is done through reflecting after a crisis subsides and looking for opportunities to improve before the next crisis hits. If the past year has taught us anything, it’s that infectious diseases aren’t going away, and we’ll always get a chance to put lessons learned to work.”

###

Additional authors on this research are Kimberly Rak, Ph.D., M.P.H., Jeremy Kahn, M.D., M.Sc., Derek Angus, M.D., M.P.H., Olivia Mancing and Julia Driessen, Ph.D., all of Pitt.

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R03HL16020, K08HL122478 and K24HL133444.

To read this release online or share it, visit https:/

About the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

As one of the nation’s leading academic centers for biomedical research, the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine integrates advanced technology with basic science across a broad range of disciplines in a continuous quest to harness the power of new knowledge and improve the human condition. Driven mainly by the School of Medicine and its affiliates, Pitt has ranked among the top 10 recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health since 1998. In rankings recently released by the National Science Foundation, Pitt ranked fifth among all American universities in total federal science and engineering research and development support.

Likewise, the School of Medicine is equally committed to advancing the quality and strength of its medical and graduate education programs, for which it is recognized as an innovative leader, and to training highly skilled, compassionate clinicians and creative scientists well-equipped to engage in world-class research. The School of Medicine is the academic partner of UPMC, which has collaborated with the University to raise the standard of medical excellence in Pittsburgh and to position health care as a driving force behind the region’s economy. For more information about the School of Medicine, see http://www.

http://www.

Contact: Allison Hydzik

Office: 412-647-9975

Mobile: 412-559-2431

E-mail: [email protected]

Contact: Wendy Zellner

Office: 412-586-9777

Mobile: 412-973-7266

E-mail: [email protected]

Media Contact

Allison Hydzik

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.