Researchers at the Medical University of South Carolina provide preclinical evidence that mental losses after traumatic brain injury can be reversed with complement inhibition, even when implemented two months after injury.

Credit: Dr. Stephen Tomlinson of the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a major cause of disability and a risk factor for early-onset dementia. The injury is characterized by a physical insult followed acutely by complement driven neuroinflammation. Complement, a part of the innate immune system that functions both in the brain and throughout the body, enhances the body’s ability to fight pathogens, promote inflammation and clear damaged cells. Complement plays a role in the brain, regardless of infection or injury, as it influences brain development and synapse formation. In TBI, complement- induced inflammation partially determines the outcome in the weeks immediately following injury. However, more research is needed to define a role for the complement system in neurodegeneration following head injury, specifically in the long-term, chronic phase of TBI. Furthermore, therapeutic management of TBI patients is limited to the acute phase following injury, as little is known about the link between the initial insult and the chronic neurodegeneration and cognitive decline in the months and years that follow.

Researchers at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), the Ralph H. Johnson VA Medical Center and elsewhere have reported a link between the complement system and the chronic phase of TBI. Their results, published online on Jan. 12 in the Journal of Neuroscience, showed that inhibition of complement at two months after TBI disrupts neurodegeneration and improves cognitive function.

“TBI is associated with cognitive decline and dementia, and there are zero pharmacological treatments to prevent that cognitive decline,” said Stephen Tomlinson, Ph.D., a professor and interim chairman of the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, who studies brain injury and the complement system.

“The vast majority of studies that have been done investigating different therapeutics in TBI have all been done with acute treatments, within hours of the initial insult. Our study is significant because we are starting treatments out to two months after TBI.”

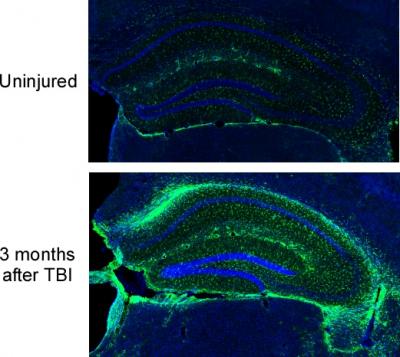

To understand more fully the timing of complement and chronic TBI, the Tomlinson Lab first looked at the body’s response to the damaged area. They showed that certain brain cells, called microglia, destroy neuronal synapses that have been marked by complement for degradation. This process reduces the overall number and density of synapses in the brain. Further, they reported ongoing complement activation up to three months after one initial TBI insult, with expanding neuroinflammation across brain regions. This inflammatory response promotes degeneration of synapses and was predictive of progressive cognitive decline.

The researchers then explored the therapeutic effects of blocking complement. They used a complement inhibitor that specifically targets sites of complement activation and brain cell injury. Inhibiting complement interrupted the decline in brain cell function and reversed mental losses on tasks that evaluate spatial learning and memory, even when delivery of the inhibitor was delayed until two months after the injury.

“One big advantage of our approach is that we do not systemically inhibit complement,” said Tomlinson.

“With acute treatments, it is not that big of an issue but chronically treating someone with a complement inhibitor systemically is not optimal because complement does other important things, ranging from host defense to controlling homeostatic and regenerative mechanisms.”

Thus far, therapeutic investigations in preclinical models have focused almost entirely on acute treatments for TBI. With this new insight into TBI pathology, the Tomlinson team suggests that all phases of injury, including chronic time points, may be responsive to therapeutic treatments, specifically those involving complement inhibition.

These findings are critical, as rehabilitative interventions are the only available management strategy for TBI to improve cognitive and motor functions. Additionally, cumulative evidence shows that rehabilitation is likely to speed up recovery but not change long-term outcomes.

“It gives us a new way of perceiving TBI management. Really, the only therapy at the moment is rehabilitation therapy, which clinically has very little benefit. We have found that rehabilitation and complement inhibition have additive effects,” said Tomlinson.

Looking forward, Tomlinson wants to take the translational approach of complement inhibition in the chronic phase of TBI out further, past that two-month window, and is investigating whether the treatment will still work in mice if it is begun six months to a year out from the initial TBI. Additionally, Tomlinson is developing models of repetitive TBI and plans to investigate anxiety and depressive behaviors in addition to early onset dementia, a significant concern in regard to veterans, soldiers and athletes.

Currently, multiple complement inhibitors are in various stages of clinical development, including those that are targeted specifically to sites of injury and disease. Tomlinson himself is a co-founder of a company that is investigating targeted complement inhibition, leading to the potential of incorporating complement inhibition into the clinic. Thus, studies undertaken in the Tomlinson lab could have deep and lasting impacts at the clinical level, where complement inhibition could eventually help the thousands of patients that suffer from TBI each year.

###

About MUSC

Founded in 1824 in Charleston, MUSC is the oldest medical school in the South, as well as the state’s only integrated, academic health sciences center with a unique charge to serve the state through education, research and patient care. Each year, MUSC educates and trains more than 3,000 students and 700 residents in six colleges: Dental Medicine, Graduate Studies, Health Professions, Medicine, Nursing and Pharmacy. The state’s leader in obtaining biomedical research funds, in fiscal year 2018, MUSC set a new high, bringing in more than $276.5 million. For information on academic programs, visit http://musc.

As the clinical health system of the Medical University of South Carolina, MUSC Health is dedicated to delivering the highest quality patient care available while training generations of competent, compassionate health care providers to serve the people of South Carolina and beyond. Comprising some 1,600 beds, more than 100 outreach sites, the MUSC College of Medicine, the physicians’ practice plan and nearly 275 telehealth locations, MUSC Health owns and operates eight hospitals situated in Charleston, Chester, Florence, Lancaster and Marion counties. In 2019, for the fifth consecutive year, U.S. News & World Report named MUSC Health the No. 1 hospital in South Carolina. To learn more about clinical patient services, visit http://muschealth.

Media Contact

Heather Woolwine

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.