Initial study flags IL-10 as potential severity marker

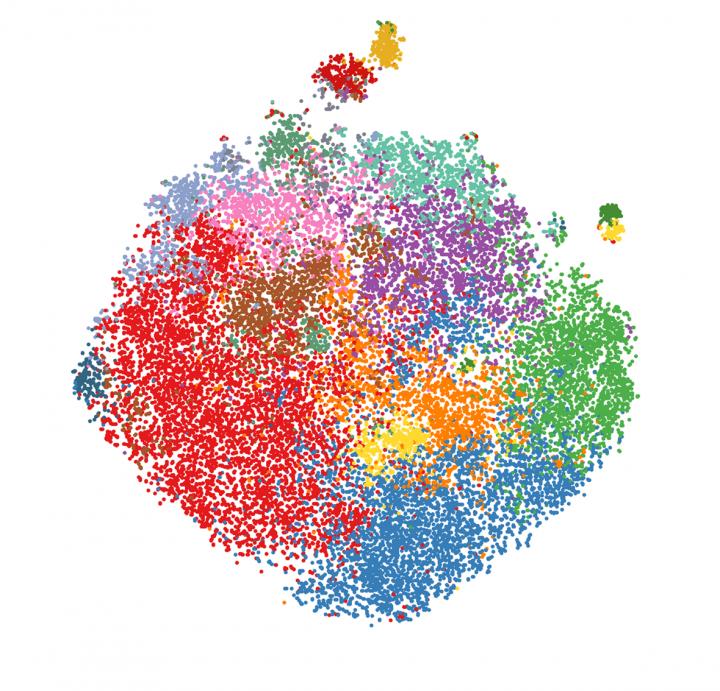

Credit: Carlos Roca (Babraham Institute) and Julika Neumann (VIB Center for Brain and Disease Research)

A team of immunology experts from research organisations in Belgium and the UK have come together to apply their pioneering research methods to put individuals’ COVID-19 response under the microscope. Published today in the journal Clinical and Translational Immunology, their research adds to the developing picture of the immune system response and our understanding of the immunological features associated with the development of severe and life-threatening disease following COVID-19. This understanding is crucial to guide the development of effective healthcare and ‘early-warning’ systems to identify and treat those at risk of a severe response.

One of the most puzzling questions about the global COVID-19 pandemic is why individuals show such a diverse response. Some people don’t show any symptoms, termed ‘silent spreaders’, whereas some COVID-19 patients require intensive care support as their immune response becomes extreme. Age and underlying health conditions are known to increase the risk of a severe response but the underlying reasons for the hyperactive immune response seen in some individuals is unexplained, although likely to be due to many factors contributing together.

To investigate the immune system variations that might explain the spectrum of responses, teams of researchers from the VIB Centre for Brain and Disease Research and KU Leuven in Belgium and the Babraham Institute in the UK worked with members of the CONTAGIOUS consortium to compare the immune system response to COVID-19 in patients showing mild-moderate or severe effects, using healthy individuals as a control group.

Professor Adrian Liston, senior group leader at the Babraham Institute in the UK, explains: “One of our main motivations for undertaking this research was to understand the complexities of the immune system response occurring in COVID-19 and identify what the hallmarks of severe illness are. We believe that the open sharing of data is key to beating this challenge and so established this data set to allow others to probe and analyse the data independently.”

The researchers specifically looked at the presence of T cells – immune cells with a diverse set of functions depending on their sub-type, with ‘cytotoxic’ T cells able to kill virus-infected cells directly, while other ‘helper’ T cell types modulate the action of other immune cells. The researchers used flow cytometry to separate out the cells of interest from the participants’ blood, based on T cell identification markers, cell activation markers and cytokine cell signalling molecules.

Surprisingly, the T cell response in the blood of COVID-19 patients classified as severe showed few differences when compared to healthy volunteers. This is in contrast to what would usually be seen after a viral infection, such as the ‘flu. However, the researchers identified an increase in T cells producing a suppressor of cell inflammation called interleukin 10 (IL-10). IL-10 production is a hallmark of activated regulatory T cells present in tissues such as the lungs. While rare in healthy individuals, the researchers were able to detect a large increase in the number of these cells in severe COVID-19 patients.

Potentially, monitoring the level of IL-10 could provide a warning light of disease progression, but the researchers state that larger-scale studies are required to confirm these findings.

“We’ve made progress in identifying the differences between a helpful and a harmful immune response in COVID-19 patients. The way forward requires an expanded study, looking at much larger numbers of patients, and also a longitudinal study, following up patients after illness. This work is already underway, and the data will be available within months,” says Professor Stephanie Humblet-Baron, at the KU Leuven in Belgium.

“This is part of an unprecedented push to understand the immunology of COVID-19”, concludes Professor Liston. “Our understanding of the immunology of this infection has progressed faster than for any other virus in human history – and it is making a real difference in treatment. Clinical strategies, such as switching to dexamethasone, have arisen from a better understanding of the immune pathology of the virus, and survival rates are increasing because of it”.

###

Media Contact

Louisa Wood

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.