The model will help speed the development of treatments and vaccines for COVID-19 and highlights the pathologic role of type I interferon signaling.

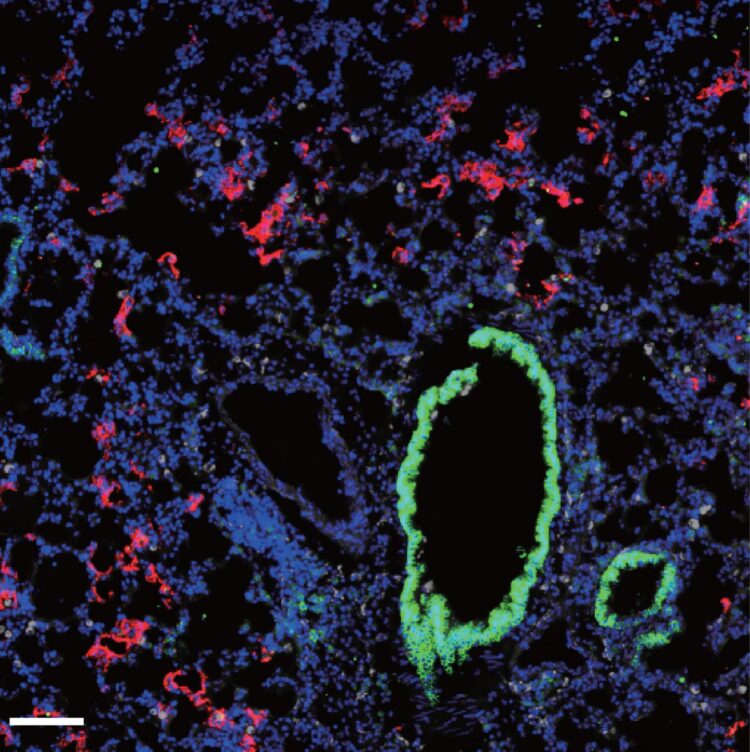

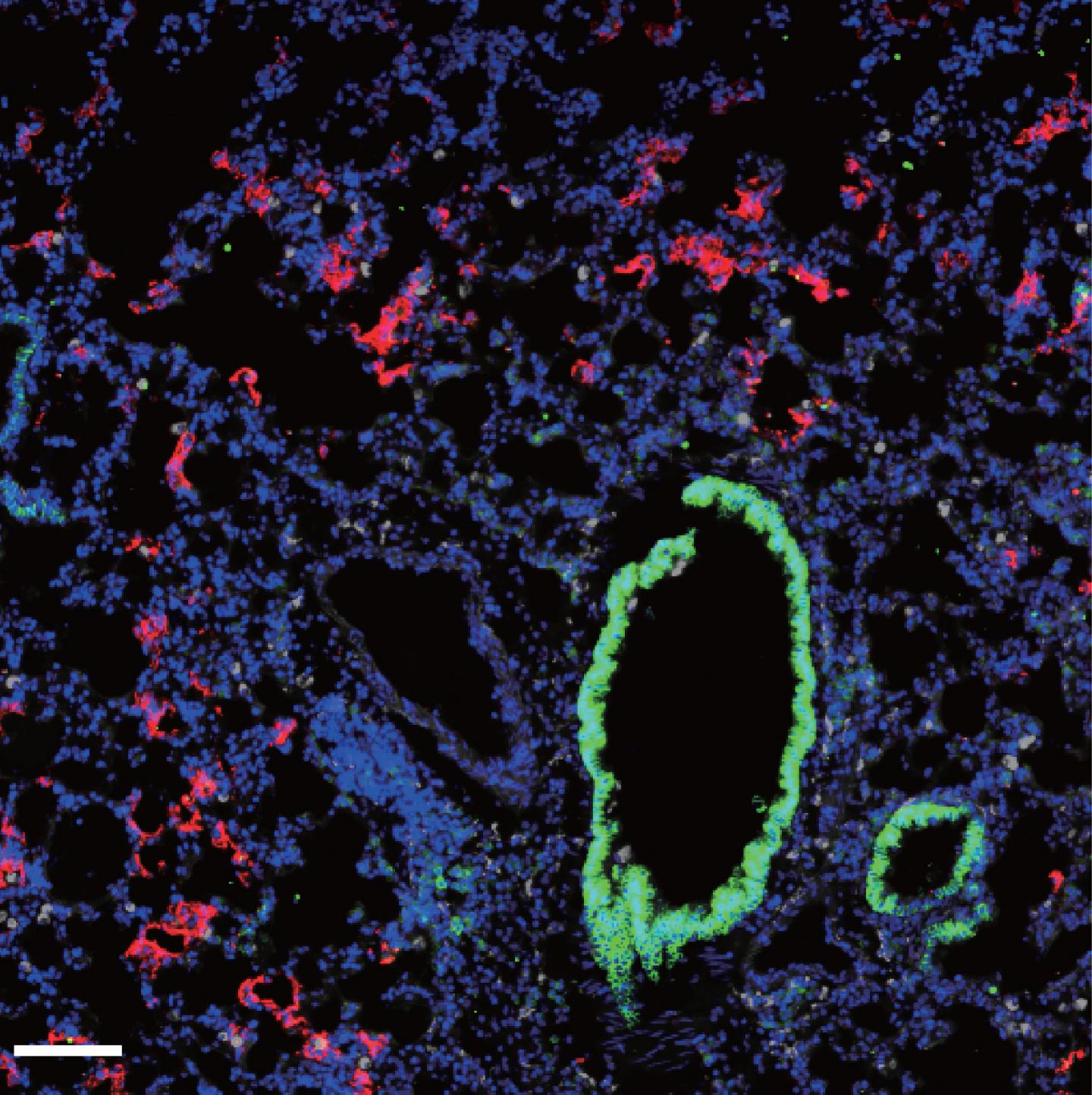

Credit: © 2020 Israelow et al. Originally published in Journal of Experimental Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20201241

Researchers at Yale University School of Medicine have developed a new mouse model to study SARS-CoV-2 infection and disease and to accelerate testing of novel treatments and vaccines against the novel coronavirus. The study, published today in the Journal of Experimental Medicine (JEM), also suggests that, rather than protecting the lungs, key antiviral signaling proteins may actually cause much of the tissue damage associated with COVID-19.

Animal models that recapitulate SARS-CoV-2 infection and disease are urgently needed to help researchers understand the virus, develop therapies, and identify potential vaccine candidates. Mice are the most widely used laboratory animals, but they cannot be infected with SARS-CoV-2 because the virus is unable to employ the mouse version of ACE2, the cell surface receptor protein that the virus uses to enter human cells.

SARS-CoV-2 can infect mice genetically engineered to produce the human version of ACE2. However, the availability of these animals is low and limited to a single mouse strain, preventing researchers from investigating how the virus impacts mice that are immunocompromised or obese, conditions that significantly increase the fatality rate in humans.

In the new study, a team of researchers led by Akiko Iwasaki at Yale University School of Medicine developed an alternative mouse model of SARS-CoV-2 infection in which the animals are first infected with a different, harmless virus carrying the human ACE2 gene. Mice infected with this virus produce the human ACE2 protein and can then be infected with SARS-CoV-2. Iwasaki and colleagues found that SARS-CoV-2 can replicate in these mice and induce an inflammatory response similar to that observed in COVID-19 patients, where a wide variety of immune cells are activated and recruited to the lungs. “In addition, the infected mice also rapidly develop neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2,” Iwasaki says.

The body’s response to viral infection often depends on signaling molecules called type I interferons that can activate immune cells and induce the production of antiviral proteins and antibodies. But too much type I interferon, especially when the production is delayed, can lead to excessive inflammation and tissue damage. Indeed, while type I interferon signaling protects against the related coronavirus MERS-CoV, it causes lung damage in response to SARS-CoV-1, the virus responsible for a previous coronavirus outbreak in 2002-2003.

The role of type I interferons in COVID-19 is currently unclear. Iwasaki and colleagues found that, similar to COVID-19 patients, mice infected with SARS-CoV-2 activate a large number of genes associated with type I interferon signaling. The researchers then used their model system to infect mice lacking key components of the type I interferon pathway and found that they were no worse at controlling SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, these animals recruited fewer inflammatory immune cells into their lungs. “These results indicate that type I interferons do not restrict SARS-CoV-2 replication, but they may play a pathological role in COVID-19 respiratory inflammation,” Iwasaki says. “This is especially concerning because type I interferons are currently being used as a treatment for COVID-19. The early timing of the IFN treatment will be important for it to provide protection and benefit.”

Iwasaki adds, “The mouse model we developed offers a broadly available and highly adaptable animal model to understand critical aspects of SARS-CoV-2 viral infection, replication, pathogenesis, and protection using authentic patient-derived virus. The model provides a vital platform for testing prophylactic and therapeutic strategies to combat COVID-19.”

###

Israelow et al., 2020. J. Exp. Med. https:/

About the Journal of Experimental Medicine

The Journal of Experimental Medicine (JEM) features peer-reviewed research on immunology, cancer biology, stem cell biology, microbial pathogenesis, vascular biology, and neurobiology. All editorial decisions are made by research-active scientists in conjunction with in-house scientific editors. JEM makes all of its content free online no later than six months after publication. Established in 1896, JEM is published by Rockefeller University Press. For more information, visit jem.org.

Visit our Newsroom, and sign up for a weekly preview of articles to be published. Embargoed media alerts are for journalists only.

Follow JEM on Twitter at @JExpMed and @RockUPress.

Media Contact

Ben Short

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.