University of Cincinnati researchers say a strain of E. coli may offer protections against its more malevolent cousins

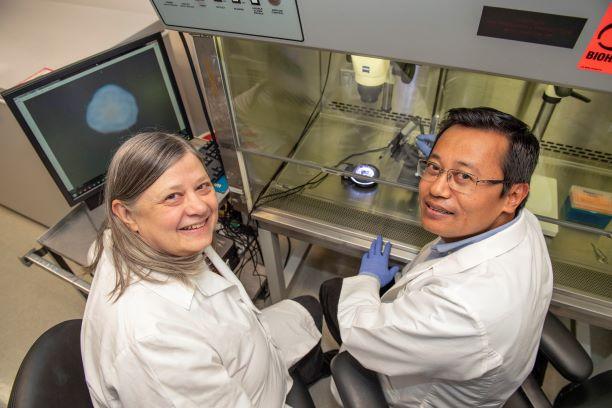

Credit: Colleen Kelley/University of Cincinnati Creative + Brand

Typically, there aren’t a lot of positive thoughts when E. coli, generally found in animal and human intestines, is mentioned. It’s been blamed for closing beaches and swimming pools and shuttering restaurants because of contamination in salad bars, meats or other food items.

But for more than a century, one strain of the bacteria, E. coli Nissle 1917, has been used as a probiotic and therapeutic agent. Currently, it is used in some countries to treat intestinal inflammation.

Now researchers at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine say E. coli Nissle may also protect human cells against other more pathogenic strains of E. coli such as E. coli 0157:H7, which is commonly associated with contaminated hamburger meat.

Alison Weiss, PhD, professor, and Suman Pradhan, PhD, research associate, both in in the UC Department of Molecular Genetics, Biochemistry and Microbiology, used stem cell-derived human intestinal organoid tissues to evaluate the safety of Nissle and its ability to protect from pathogenic E. coli bacteria 0157:H7.

They found that human intestinal tissues (HIO) were not harmed by the Nissle bacteria introduced into human intestinal organoids while pathogenic E. coli bacteria destroyed the epithelial layer of the HIO. More importantly, Nissle protected the HIOs when added prior to pathogenic E. coli bacterial infection.

The study’s findings are available online in mBio, the scholarly journal of the American Society for Microbiology.

“Nissle did not kill pathogenic E. coli, but rather ramps up your intestinal responses and prepares you for possible pathogens attacking the intestine,” explains Weiss, corresponding author of the study. “We don’t know how it does this, but our study confirms its effectiveness in human cells. Our hope is to figure out how this is happening.”

“There are all sorts of flavors of E. coli,” says Weiss. “They gather genes from all over the place and channel a whole bunch of other pathogens. There are E.coli which can also cause urinary tract infections. What is special is that bad E. coli have a chunk of extra genes that allow them to cause problems. The good E. coli are stripped down of these genes and they don’t have the capacity to do bad things.”

Weiss says they hope to learn more about the abilities of Nissle in order to develop a treatment of E. coli infections that often result from the production of Shiga toxins. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 265,000 such infections occur annually causing stomach cramps, diarrhea and vomiting. Cases can be mild to severe and affect people of all ages, though the illness can be particularly hard on smaller children, who are more likely to die from an infection, says Weiss. Moreover, antibiotic treatment of children with E. coli 0157:H7 infection increases the risk of hemolytic-uremic syndrome.

“Right now there is no cure for an E. coli infection,” says Weiss. “We can give individuals fluids, but it can be really deadly and it would be really nice for us to figure out how to cure it.”

“E. coli is carried asymptotically by all sorts of animals and released into their fecal matter and then leading to possible contamination if it comes into contact with food items or is ingested,” says Weiss. “It is difficult though still possible to screen meat for E. coli. The best possible protection is to cook meat properly before consuming it. E. coli is also found in raw vegetables such as lettuce and it can be difficult to detect and remove.”

###

The study conducted by Weiss and Pradhan was supported by National Institutes of Health grants U19-AI116491 and R01AI139027 and by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant P30 DK078392.

Media Contact

Cedric Ricks

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/