Publication in the Journal of the American Chemical Society

Credit: L. Hartmann, M. Schelhaas

Viruses are part of the human experience throughout our lives. They cause lots of different illnesses with the current coronavirus pandemic as just one example. While a vaccine does provide effective protection from viral infections, vaccines are only available for a select number of viruses. This is why antiviral drugs need to be found that can prevent or treat a viral infection.

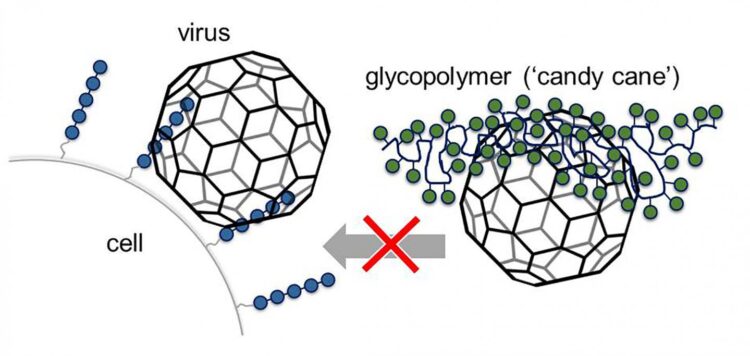

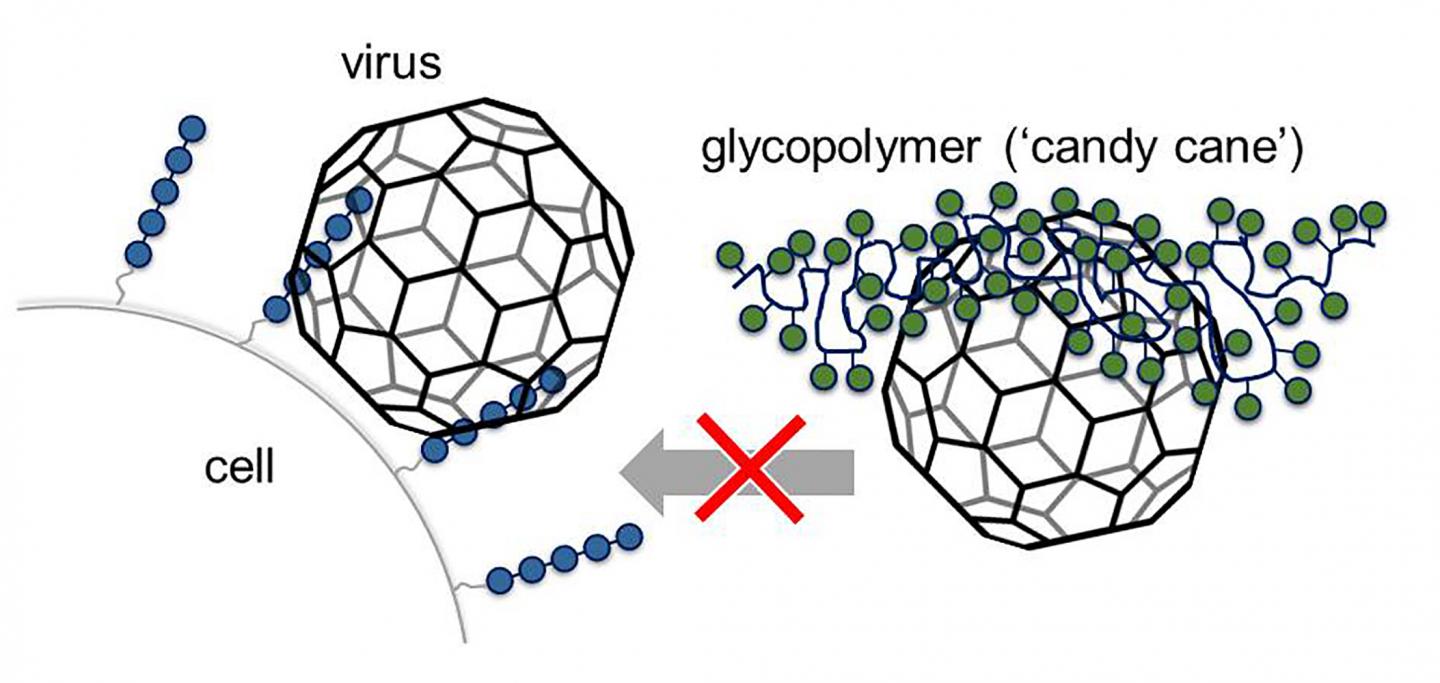

One successful strategy involves special molecules to block viral proteins that would otherwise help the virus to attach to the host cell. Once a virus has attached to the cell surface, it can infect the cell with its genome and reprogram the cell for its own uses. However, many antiviral drugs lose their effect over time, as viruses mutate very quickly and thus often adapt to the medication/antiviral used.

The research team led by HHU Prof. Dr. Laura Hartmann from the Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry and Münster-based Prof. Dr. Mario Schelhaas from the Institute of Cellular Virology working together with Prof. Dr. Nicole Snyder from Davidson College in North Carolina, USA has used the approach of suppressing the initial contact between the virus and the cell in order to stop infection at the onset.

Viruses frequently use special proteins to bind to sugar molecules on the cell surface. Among others, these sugars include long-chain glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), which are strongly negatively charged. One of these GAGs is heparan sulfate. Researchers already knew that GAGs can reduce virus infections if they are added externally. However, natural polysaccharides may have side-effects that are attributed to their own biological function in the organism or to impurities.

The research team is now using the benefits of the GAGs but deactivates their disadvantages. The idea is to use molecules produced artificially and in a controlled fashion, so called ‘glycomimetics’, that are developed at HHU. They comprise a long synthetic scaffold with side chains with small sugar molecules attached. In Düsseldorf, both shorter chains with up to ten lateral sugars (known as ‘oligomers’) and long chains with up to 80 sugars (called ‘glycopolymers’) have been created. In order to simulate the highly charged state of natural GAGs, the chemists coupled sulfate groups to the sugars.

Prof. Schelhaas then used cell cultures to test the antiviral properties of these ‘candy canes’ of varying length at University Hospital Münster. Initially, his team used them against Human Papillomaviruses, which can trigger diseases such as cervical cancer. They discovered that both, the short and long-chain synthetic molecules, have an antiviral effect, but their mode of action is different. As expected, the more effective, long-chain molecules prevented the virus from attaching to cells. In contrast, the short-chain molecules displayed antiviral activity after attachment to the cell, giving rise to the assumption that these molecules are active in the organism for longer.

This is what Prof. Schelhaas has to say: “It is very likely that the long-chain molecules occupy the binding sites of the virus to the cell and thus block those sites. The short-chain molecules apparently do not block these sites. The next step is to test our hypothesis that these molecules prevent the redistribution of proteins in the virus particle so that the viruses cannot infect the cell.”

Effectiveness was also confirmed for the Papillomaviruses in an animal model. The compounds were also active against four other viruses, including Herpes viruses, which can cause cold sores and encephalitis, and Influenza viruses, which cause the flu. Prof. Hartmann explains: “Glycomimetics are thus promising compound molecules that could potentially be used in the fight against a large number of different viruses. The next thing to do is to examine the precise way in which the glycomimetics work and how they can be further optimised.”

Prof. Schelhaas adds: “Further research will focus on how fast viruses may adapt to this new class of compounds. With the short-chain molecules in particular, we are hopeful that viruses will find it harder to launch a counterattack.”

###

The project was supported by the German Research Foundation within the framework of funding the Virocarb Research Unit and by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research as part of funding for the European Infect-ERA consortium HPV-MOTIVA. In addition, the Heine Research Academies (HeRA) at HHU funded the exchange programme with Prof. Snyder’s group.

Original publication

Laura Soria-Martinez, Sebastian Bauer, Markus Giesler, Sonja Schelhaas, Jennifer Materlik, Kevin Janus, Patrick Pierzyna, Miriam Becker, Nicole L. Snyder, Laura Hartmann and Mario Schelhaas, Prophylactic Antiviral Activity of Sulfated Glycomimetic Oligomers and Polymers, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 11, 5252-5265

DOI: 10.1021/jacs.9b13484

Media Contact

Arne Claussen

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.