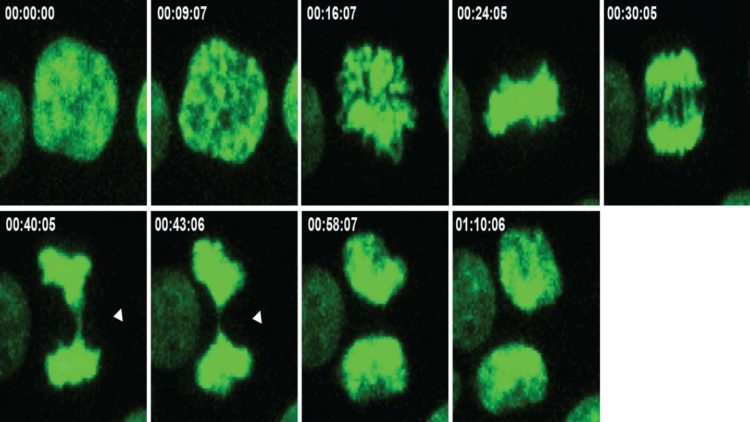

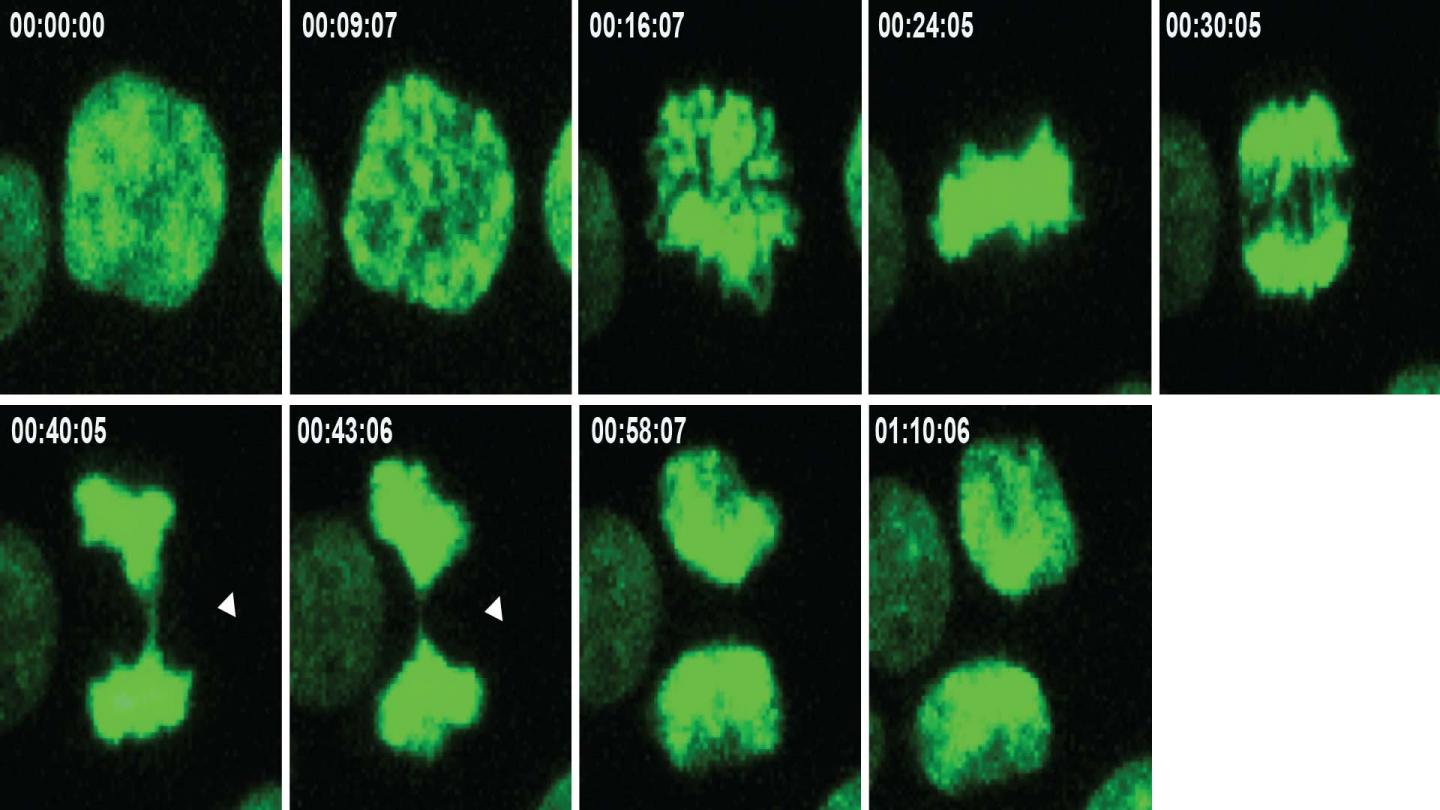

Credit: Sheltzer lab/CSHL, 2020

Cancer cells are notorious for their genetic disarray. A tumor cell can contain an abundance of DNA mutations and most have the wrong number of chromosomes. A missing or extra copy of a single chromosome creates an imbalance called aneuploidy, which can skew the activity of hundreds or thousands of genes. As cancer progresses, so does aneuploidy. Some advanced tumors can harbor cells that have accumulated more than 100 chromosomes, instead of 46 in normal cells.

High levels of aneuploidy are associated with aggressive cancers and a poor prognosis for patients. But according to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory investigator Jason Sheltzer and colleagues, not all aneuploidies spur cancer’s progression. In the journal Developmental Cell, they report that some aneuploidies inhibit a cancer’s ability to metastasize.

Sheltzer says that although aneuploidy is very common in cancer cells, it hasn’t been clear whether these abnormalities help drive the disease. His team collaborated with Zuzana Storchová at the University of Kaiserslautern, developing new tools to investigate how cancer cells’ behavior changes when they acquire an extra chromosome. They engineered sets of human cells that each had an extra copy of a different chromosome, but were otherwise identical.

When postdoctoral researcher Anand Vasudevan tested these cells in the laboratory, the results were surprising. “Since highly aggressive cancers tend to be aneuploid, we expected that all or most aneuploidies would contribute to metastatic behavior,” Sheltzer says. “But it is actually a more complicated relationship. We found that different chromosomes can have all sorts of different impacts.” Some extra chromosomes had no impact on metastasis, whereas others actually suppressed it.

Analysis of patient data revealed something similar. While survival is poorest among patients whose cancers have a high level of aneuploidy overall, the team identified certain chromosomes for which extra copies were associated with increased survival. These beneficial aneuploidies were less common than those linked to poor survival. This is probably because changes that help a tumor flourish are the ones most likely to persist as the disease progresses. Their presence indicates that the clinical impacts of aneuploidy are likely to be just as complicated as the lab experiments suggest, Sheltzer says.

Sheltzer’s team is exploring the single aneuploidy that enhanced metastasis in their experiments to understand how an extra copy of that chromosome strengthens cancer cells’ invasive behavior. They will also use their new aneuploid cell lines to screen for potential drugs and genetic changes that eliminate cancer cells by targeting these abnormalities.

###

Media Contact

Sara Roncero-Menendez

[email protected]

516-367-6866

Related Journal Article

http://dx.