Credit: UPMC

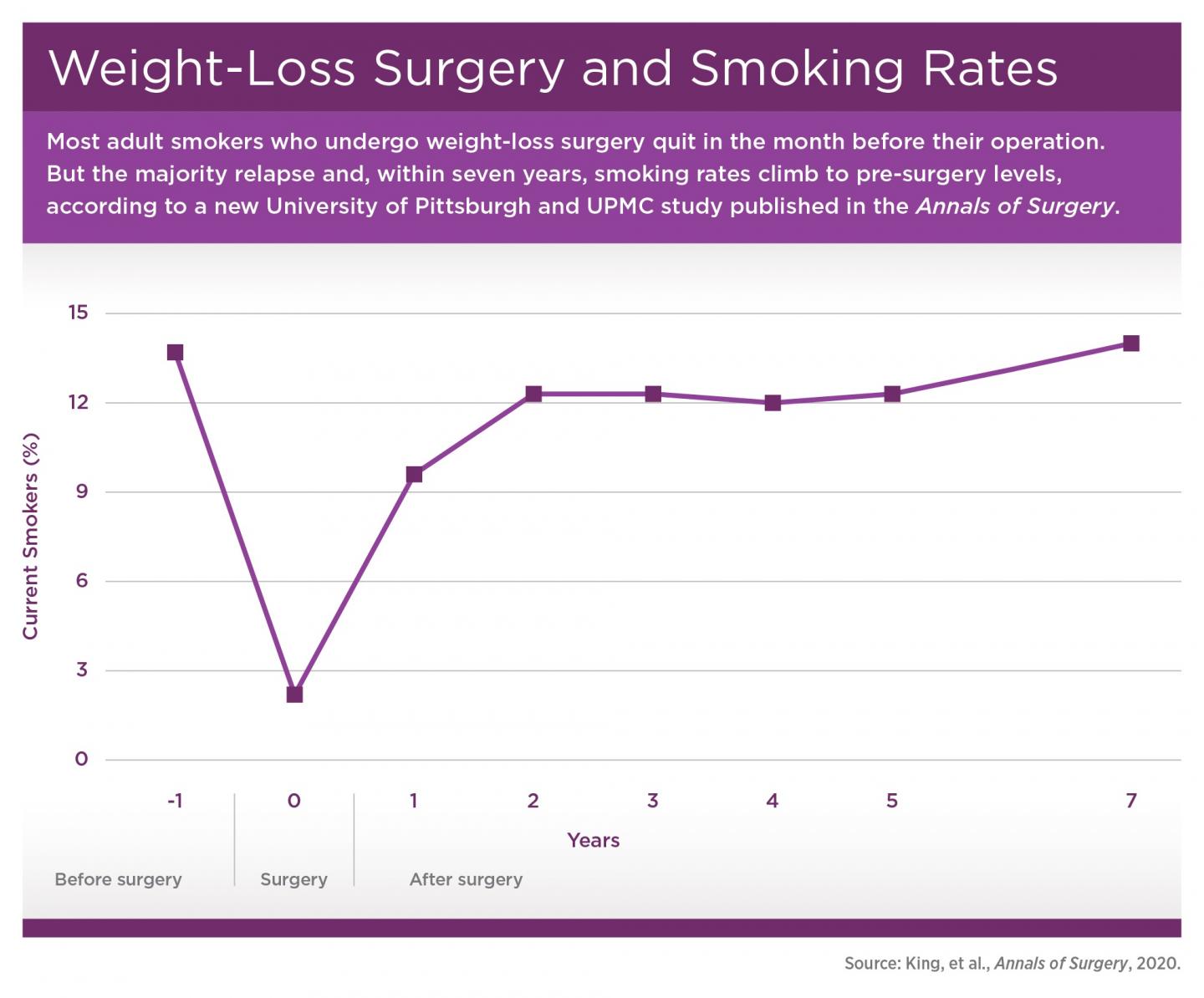

PITTSBURGH, Feb. 21, 2020 – Although 1 in 7 adults smoke cigarettes the year prior to undergoing weight-loss surgery, nearly all successfully quit at least a month before their operation. However, smoking prevalence steadily climbs to pre-surgery levels within seven years, according to new research led by the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health.

The findings — reported today in the Annals of Surgery — suggest that there may be missed opportunities to engage patients in interventions to improve long-term smoking cessation rates, particularly at regular post-surgery checkups.

“Smoking cessation prior to surgery is strongly recommended to reduce surgical complications,” said lead author Wendy King, Ph.D., associate professor of epidemiology at Pitt Public Health. “But there isn’t the same emphasis on maintaining cessation after surgery. Our findings show that there is a need for ongoing support in order to reduce and quickly respond to relapses.”

King and her colleagues followed 1,770 adults who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery — a procedure that reduces the size of the stomach and bypasses part of the small intestine — for seven years post-surgery, annually surveying them about their smoking habits. The participants were enrolled in the National Institutes of Health-funded Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery-2 (LABS-2), a prospective, observational study of patients undergoing weight-loss surgery at one of 10 hospitals across the United States.

More than 45% of the participants reported a history of smoking prior to surgery, with 14% still smoking in the year before surgery, which fell to 2% in the month before surgery. The rate rebounded to nearly 10% in the year following surgery and steadily climbed back to 14% by seven years post-surgery.

“Interestingly, the people who picked up smoking post-surgery weren’t just the people who quit smoking in the year prior to surgery, presumably to prepare for the operation. Many had never smoked to begin with,” said co-author Gretchen White, Ph.D., assistant professor in Pitt’s School of Medicine, explaining that 2 out of 5 people who smoked after surgery had quit more than a year before their operation or hadn’t ever smoked.

Additionally, people who identified as smokers post-surgery smoked more, going from an average of a dozen cigarettes per day in the year before surgery to more than 15 cigarettes per day seven years post-surgery. These findings contrast with concurrent reductions in smoking prevalence and intensity in the general U.S. population.

The researchers hypothesized that weight control would be a key reason weight-loss patients took up smoking after surgery, but found that the prevalence of smoking for weight control was actually fairly stable over time, at about 2% pre- and post-surgery, and did not appear to be related to smoking more cigarettes. King noted that “this surprised everyone, as there is a general assumption that weight control is a main motivator for smoking.”

While the study was not designed to find a biological reason for the results, the researchers did observe that gastric bypass patients were more likely to smoke post-surgery than patients who underwent gastric banding, where a silicone belt is surgically inserted around the stomach to reduce the amount of food it can hold. A recent study showed that gastric bypass increases exposure to the psychoactive nicotine metabolite cotinine. Just as gastric bypass increases the risk of alcohol use disorder due to changes in alcohol metabolism that lead to higher and quicker elevation of blood alcohol levels, it may also increase risk of smoking via nicotine metabolism, King suggested.

The scientists identified several factors that predict which patients would be most likely to take up smoking after surgery. Not surprisingly, a prior history of smoking was the greatest risk factor. In addition, younger age, poverty, being married or living as married, and drug use were each associated with increased risk.

###

The senior author on this research is Anita P. Courcoulas, M.D. Additional authors are Steven H. Belle, Ph.D., and Bestoun Ahmed, M.D., both of Pitt; Susan Z. Yanovski, M.D., of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK); Alfons Pomp, M.D., of Weill Cornell Medical College; and Bruce M. Wolfe, M.D., of Oregon Health & Sciences University.

This clinical study was a cooperative agreement funded by the NIDDK. Grant numbers are: Data Coordinating Center – U01 DK066557; Columbia-Presbyterian – U01-DK66667 (in collaboration with Cornell University Medical Center CTSC, grant UL1-RR024996); University of Washington – U01-DK66568 (in collaboration with CTRC, grant M01RR-00037); Neuropsychiatric Research Institute – U01-DK66471; East Carolina University – U01-DK66526; UPMC – U01-DK66585 (in collaboration with CTRC, grant UL1-RR024153); and Oregon Health & Science University – U01-DK66555.

To read this release online or share it, visit https:/

About the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health

The University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, founded in 1948 and now one of the top-ranked schools of public health in the United States, conducts research on public health and medical care that improves the lives of millions of people around the world. Pitt Public Health is a leader in devising new methods to prevent and treat cardiovascular diseases, HIV/AIDS, cancer and other important public health problems. For more information about Pitt Public Health, visit the school’s Web site at http://www.

http://www.

Contact: Allison Hydzik

Office: 412-647-9975

Mobile: 412-559-2431

E-mail: [email protected]

Contact: Erin Hare

Office: 412-864-7194

Mobile: 412-738-1097

E-mail: [email protected]

Media Contact

Allison Hydzik

[email protected]

412-647-9975

Related Journal Article

http://dx.