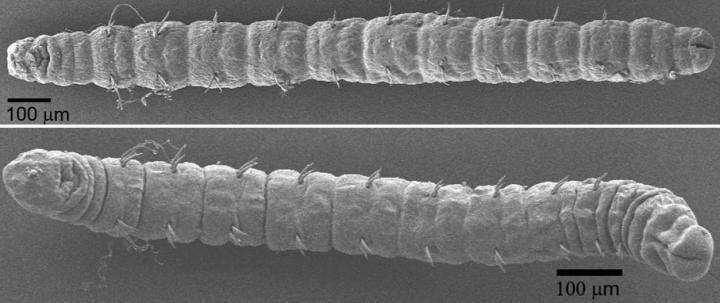

Credit: José Cerca, Christian Meyer, Günter Purschke, Torsten H. Struck

That size, shape and structure of organisms can evolve at different speeds is well known, ranging from fast-evolving adaptive radiations to living fossils such as cichlids or coelacanths, respectively.

A team lead by biologists at the Natural History Museum (University of Oslo) has uncovered a group of species in which change in appearance seems to have been brought to a complete halt.

The tiny annelid worms belonging to the genus Stygocapitella live in sandy beaches around the world. In their 275-million-year-old history the worms have evolved ten distinct species.

But what makes the group stand out is its presence of only four different appearances, or morphotypes. Such absence of morphological change has lately proven to be a common feature of many so-called cryptic species complexes, for example, in mammals, snails, crustaceans or jellyfishes.

– Cryptic species are species which have already been distinct species for a substantial amount of time, but have accumulated very little or no morphological differences.

– Such species can help us understand how evolution proceeds in the absence of morphological evolution, and which factors might be important in these cases, explains professor Torsten Struck at the Natural History Museum (University of Oslo)

Two of the Stygocapitella species that were investigated split apart at the same time when the Stegosaurus and Brachiosaurus roamed about.

But despite 140 million years of evolution, these ghost worms today look almost exactly the same. However, looks may be deceiving. Molecular investigations reveal that they are highly genetically distinct, and considered reproductively isolated species.

In comparison to other cryptic-species complexes that are separated by a maximum of a couple million years, the time span in this complex is ten times longer, which makes the lack of change in ghost worms extreme.

– These species can also be studied to understand how species respond to extreme ecological changes in the long run. Some of these morphotypes have experienced the much warmer conditions of the Cretaceous as well as the changing intervals of the ice ages, says Struck.

What makes the case of Stygocapitella particularly puzzling is that closely related taxa seem to be evolving morphotypes significantly faster. The findings therefore highlight that evolutionary change in appearance should be viewed as a continuum, ranging from accelerated to decelerated, and where the investigated worms stand out as one of the more extreme cases of the latter. The study also points out that species formation is not necessarily accompanied by morphological changes.

The researchers suggest that lack of morphological change may be linked to the worms having adapted to an environment that has changed little over time.

– Beaches have always been around and had the same composition then as now. We suspect these worms have remained in the same environment for millions and millions of years and they are well adapted. We suspect they have become good in moving around, but not having changed much, explains first author of the study PhD Fellow José Cerca.

– Alternatively, it has been suggested that populations regularly crash to only a few surviving individuals, and newly evolved characters get eliminated in the course of these events. Finally, besides or instead of the environment their development may constrain their evolution.

However, the reasons for the slow rate rare as of yet inconclusive in the current study, and remains to be tested by the group in the future.

###

Publication:

Deceleration of morphological evolution in a cryptic species complex and its link to paleontological stasis (2019) José Cerca, Christian Meyer, Dave Stateczny, Dominik Siemon, Jana Wegbrod, Gunter Purschke, Dimitar Dimitrov and Torsten H. Struck

Media Contact

Torsten Hugo Struck

[email protected]

47-228-51740

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.