Credit: Colleen Kelley/University of Cincinnati

CINCINNATI–A University of Cincinnati (UC) College of Medicine researcher is trying to determine how opioids interact with HIV and the medications used to manage it in the search for new therapies to better assist individuals battling addiction and living with HIV.

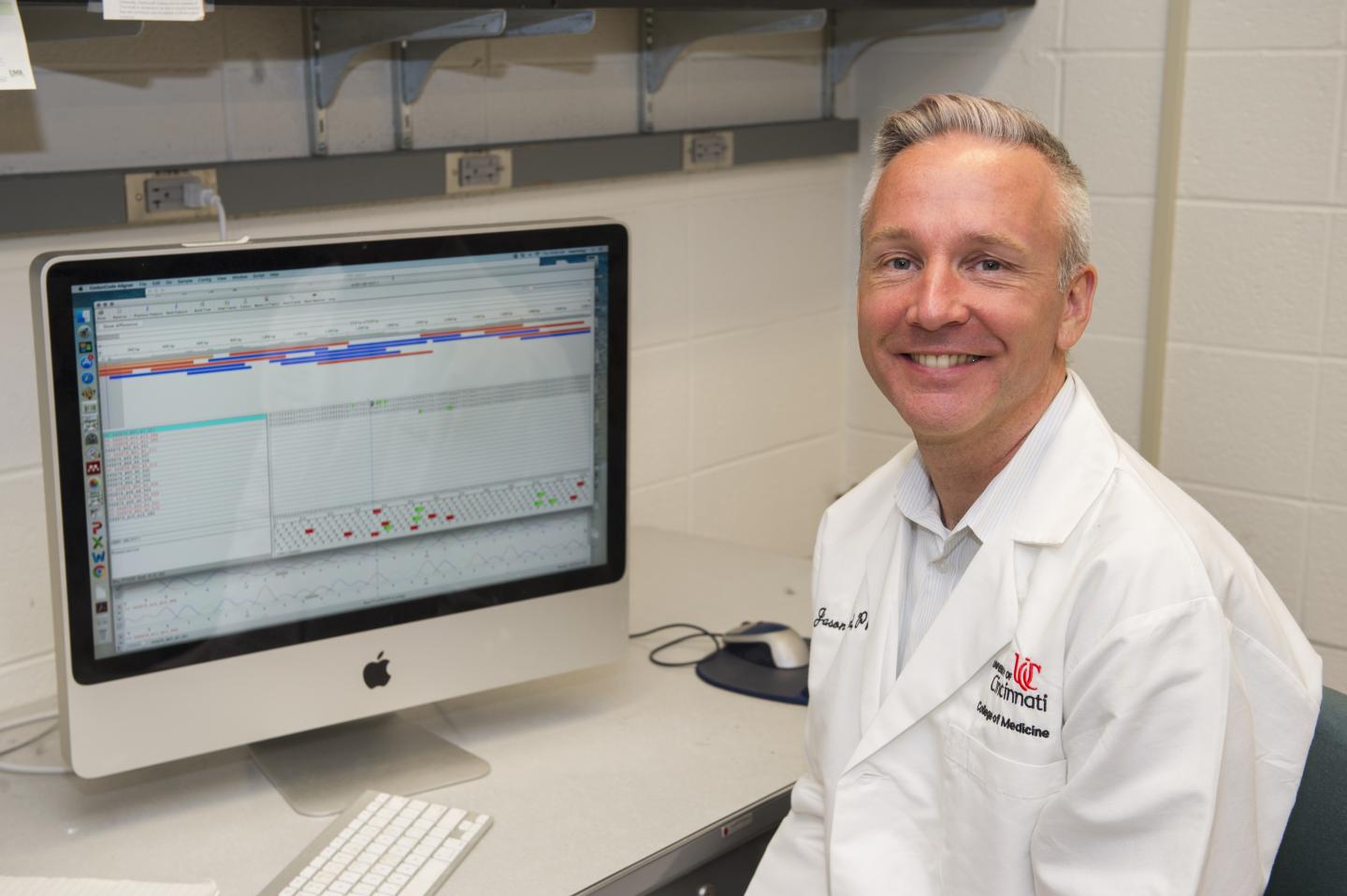

Jason Blackard, PhD, associate professor in the UC Department of Internal Medicine’s Division of Digestive Diseases, has secured a $1.7 million National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) grant awarded over a three-year period to conduct an omics analysis of synthetic opioids and HIV.

“This is a complex issue. We have a very poor understanding of how HIV impacts opioids or how opioids impact HIV. We don’t know if current therapies will work as well as they normally do,” says Blackard, whose translational research laboratory studies virus-virus and virus-host interactions. “What is the interaction between these synthetic opioids that are commonly found in high-risk individuals and some of the infections that might be associated with drugs of abuse like HIV or Hepatitis C virus?”

In 2017, an estimated 1.7 million people in the United States suffered from substance use disorders related to prescription opioid pain relievers and 652,000 suffered from a heroin use disorder, according to NIDA. About 47,000 Americans that same year died as a result of opioid overdose–a statistic that includes the use of prescription opioids, heroin and illegally manufactured synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, per NIDA.

Drug users often share needles when using injectable opioids, an action that increases the risk of contracting HIV and Hepatitis C virus.

A key advantage of this project is its multi-disciplinary approach. Co-investigators involved in the study include UC faculty and UC Health clinicians: Michael Lyons, MD, associate professor of emergency medicine, and Jennifer Brown, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry. They will help Dr. Blackard in bridging the divide between basic and clinical science that this translational research project is designed to address.

Blackard says the research project will include an observational study in humans as well as ex vivo experiments using blood samples manipulated and exposed to HIV and/or synthetic opioids in the laboratory. As part of the clinical trial, Blackard will work closely with clinicians and health professionals to enroll 25 patients annually over the grant period who come to UC Medical Center’s emergency room as a result of drug overdose.

When patients presenting with opioid-related overdose are seen by an emergency physician, blood is drawn to determine what substance is present in their bodies. Many of these individuals may already know their HIV status, while others may require additional testing for HIV, explains Blackard.

Blackard says the observational study focuses on individuals with HIV so he is looking for patients who are HIV positive and battling addiction. “What we will do is measure their viral load; it is the measure of how much virus is in the body. It also tells us how well HIV treatments are working and provides important information about disease progression,” he explains.

“There are a whole bunch of markers of HIV disease we can measure. What is it doing to the cells that are infected in the first place? We know that people with opioid use disorders relapse quite frequently. We know that people who are relapsing may not adhere to their HIV medications or they may chose not to take them or they may not work,” says Blackard.

“So, we have to take this relatively holistic approach to saying, you know what we probably need is new medications or additional medications to treat opioid use disorder in the context of HIV or some other chronic infection because these two things are synergetic, but they are helping each other along in a bad way.”

Ex vivo experiments also yield important information for the research study, says Blackard.

“In my lab we grow HIV, Hepatitis C, Hepatitis B and we take something we grow in a petri dish and add it to blood sample that we took from a patient,” says Blackard. “We do the same measure of replication; how well does HIV grow in the presence of an opioid?

“It helps us determine what medications we should use or how we intervene,” says Blackard. “If we know the drugs of abuse promote HIV replication then maybe we need to have a discussion about pre-exposure prophylaxis.”

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) involves using antiviral drugs in people not yet exposed to HIV/AIDS to prevent infection. PrEP is sometimes offered to subpopulations deemed at high risk of HIV infection.

“Maybe we need to look at what specific combinations of drugs work the best for reducing HIV replication for people that are injecting versus those that don’t,” says Blackard. “Perhaps a certain recognition there are certain types of drugs that may not be appropriate for injection drug users, but they might be appropriate for other subpopulations at risk for HIV.”

“At the end of the day, we are really limited in what we have to treat substance abuse in people that have something else,” says Blackard. “Even though we talk about how we treat the HIV, which we do reasonably well, we do a poor job of also treating the substance abuse.”

###

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health NIDA grant 1R61DA048439-01.

Media Contact

Cedric Ricks

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/