Credit: Michigan Medicine

A trip to an intensive care unit can be more than twice as costly as a stay in a non-ICU hospital room, but a new study finds intensive care is still the right option for some vulnerable patients after a severe heart attack.

The difficulty lies in determining which people are best served in the ICU while they recover.

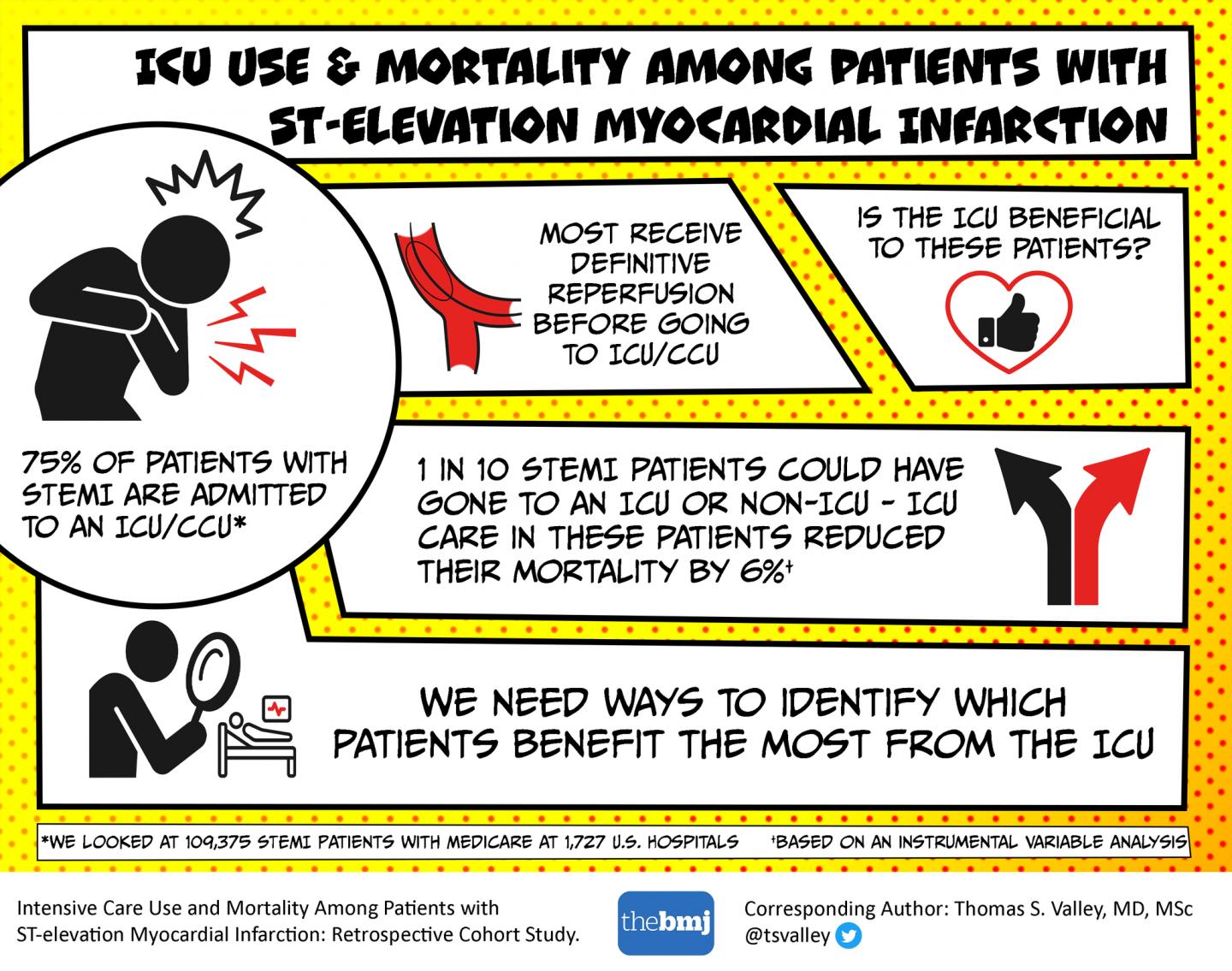

The new Michigan Medicine (University of Michigan) research, published in The BMJ, found ICU admission was associated with improved 30-day mortality rates for patients who had a STEMI heart attack and weren’t clearly indicated for an ICU or non-ICU unit.

“For these patients who could reasonably be cared for in either place, ICU admission was beneficial,” says lead author Thomas Valley, M.D., M.Sc., an assistant professor of internal medicine at Michigan Medicine, who cares for patients in the intensive care unit.

But Valley cautions against simply continuing to send nearly everyone to the ICU.

“ICU care is a treatment just like any medication,” Valley says. “Providers need to know whether it’s right for an individual person just like we try to do with a prescription drug.”

The researchers analyzed Medicare data from more than 100,000 patients hospitalized with STEMI, or ST-elevation myocardial infarction, a dangerous heart attack that requires quick opening of the blocked blood vessel to restore blood flow. Those patients were hospitalized at 1,727 acute care hospitals across the U.S. in a nearly two-year period from January 2014 to October 2015, and most were sent to the ICU after treatment.

“A lot of the focus is on getting these people to the cardiac catheterization lab as soon as possible to open up the blood vessel, but less is known about what you do after that,” Valley says.

Current U.S. guidelines don’t address whether to send patients to the ICU, while European guidelines recommend the ICU.

Valley says providers could use more clear guidance on how to make these decisions.

In this study, the mortality rate was 6.1% lower after 30 days for those admitted to their hospital’s ICU. Valley says the surprising results–in the face of other studies that show ICU overuse–demonstrate that ICU care is misdirected.

‘An important debate in cardiology’

This study addresses an important issue in ICU care, says Michael Thomas, M.D., an assistant professor of internal medicine who runs the Cardiac ICU at Michigan Medicine’s Cardiovascular Center.

“At Michigan Medicine, all of our STEMI patients are admitted to the Cardiac ICU,” says Thomas, who was not involved with the BMJ paper. “However, knowing where to send these patients after STEMI is an important debate in cardiology right now.”

“Some recent studies suggest many patients don’t need ICU level of care and that it wastes resources. But before we pull back from this model, we need to understand this problem more fully,” he says.

Across the nation, 75% of STEMI heart attack patients are sent to the ICU, most of the time after reperfusion treatment in the cath lab to open up the blocked vessel.

ICU vs. non-ICU care

People recovering from a STEMI are some of the very sick patients ICUs were originally designed for, so providers may not even think about disrupting the longtime status quo, Valley says.

“The historical thinking was, ‘Why not send everyone to the ICU?’ Now, we see that there are risks associated,” Valley says. “For example, in the ICU, you’re more likely to have a procedure, whether you need it more or not.

“We must also consider the risk of infection, sending someone to a unit full of really sick patients who might have C. diff or other serious infections.”

The sleep quality as people are recovering from their heart attacks may also be lower in the ICU, because patients are given such close nursing care, Valley says.

That’s necessary for the sickest patients, but it might be disruptive to those people on the bubble who could be getting better rest on a regular floor, he says.

Medicare has requirements for what constitutes ICU care, such as high nurse staffing levels and access to lifesaving care.

“Because of Medicare requirements, ICUs tend to be more similar across hospitals than non-ICUs,” Valley says.

“Perhaps some hospitals can take care of patients anywhere, while others really need to use the ICU at high rates in order to provide safe care.”

A clear benefit for some, increased cost for others

Valley says these data show a clear benefit of ICU care for vulnerable patients, as opposed to non-STEMI patients studied who did not have a significant difference in mortality rates with or without ICU admission.

“Physicians might look at STEMI patients and wonder, ‘Do they really need the ICU? Could it harm them? Is it a good use of resources?'” Valley says.

Valley, a member of U-M’s Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation, has previously found ICU overuse occurred for less critical patients hospitalized for a flare-up of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or heart failure. In that study, ICU admission dramatically increased cost of care without an increased survival benefit.

The next step, according to Valley, is to determine what is beneficial about the ICU for those patients who benefit from it. He says that could lead to hospitals adopting some ICU care practices on non-ICU floors.

Valley hopes making non-ICU floors more similar to the ICU in some ways could improve outcomes while reducing cost of care and infection risk.

###

Media Contact

Haley Otman

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.