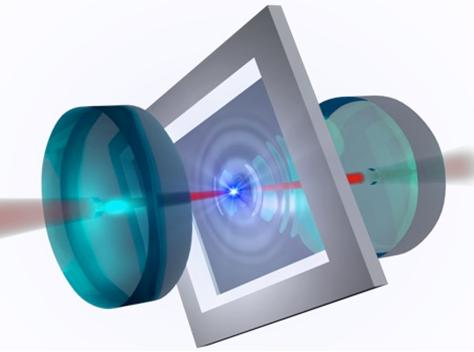

Credit: Harris Lab/Yale University

New Haven, Conn. – Imagine being able to hear people whispering in the next room, while the raucous party in your own room is inaudible to the whisperers. Yale researchers have found a way to do just that — make sound flow in one direction — within a fundamental technology found in everything from cell phones to gravitational wave detectors.

What’s more, the researchers have used the same idea to control the flow of heat in one direction. The discovery offers new possibilities for enhancing electronic devices that use acoustic resonators.

The findings, from the lab of Yale’s Jack Harris, are published in the April 4 online edition of the journal Nature.

“This is an experiment in which we make a one-way route for sound waves,” said Harris, a Yale physics professor and the study’s principal investigator. “Specifically, we have two acoustic resonators. Sound stored in the first resonator can leak into the second, but not vice versa.”

Harris said his team was able to achieve the result with a “tuning knob” — a laser setting, actually — that can weaken or strengthen a sound wave, depending on the sound wave’s direction.

Then the researchers took their experiment to a different level. Because heat consists mostly of vibrations, they applied the same ideas to the flow of heat from one object to another.

“By using our one-way sound trick, we can make heat flow from point A to point B, or from B to A, regardless of which one is colder or hotter,” Harris said. “This would be like dropping an ice cube into a glass of hot water and having the ice cubes get colder and colder while the water around them gets warmer and warmer. Then, by changing a single setting on our laser, heat is made to flow the usual way, and the ice cubes gradually warm and melt while the liquid water cools a bit. Though in our experiments it’s not ice cubes and water that are exchanging heat, but rather two acoustic resonators.”

Although some of the most basic examples of acoustic resonators are found in musical instruments or even automobile exhaust pipes, they’re also found in a variety of electronics. They are used as sensors, filters, and transducers because of their compatibility with a wide range of materials, frequencies, and fabrication processes.

###

The first author of the study is former Yale postdoctoral associate Haitan Xu. Co-authors of the study are Yale graduate student Luyao Jiang and A.A. Clerk of the University of Chicago.

The work is supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, the Office of Naval Research, and the Simons Foundation.

Media Contact

Jim Shelton

[email protected]