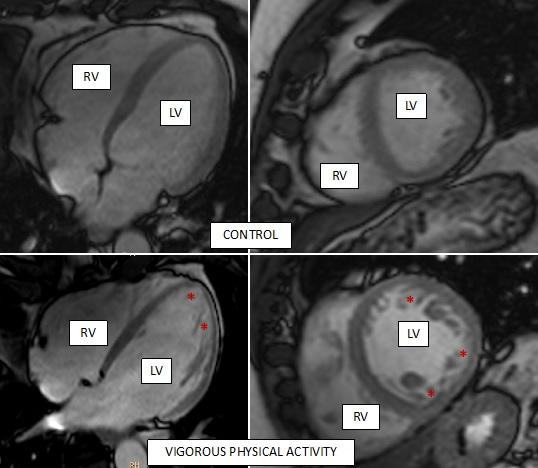

CNIC scientists have shown that vigorous physical exercise is linked to “noncompaction” of the heart, causing it to acquire a spongy appearance

Credit: CNIC

Exercising regularly, whether intensely or moderately, is a health recommendation accepted by all experts. Nevertheless, high-intensity physical training can trigger a series of physiological changes in the body, including the heart. The hearts of professional athletes adapt to training in a number of ways, including by increasing the number of structures called trabeculae in the inside of the heart. While this process, called hypertrabeculation, is harmless in athletes, it is also a pathological feature of the hereditary disease noncompaction cardiomyopathy, which can cause sudden cardiac death.

Now, scientists at the Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC) have used cardiac magnetic resonance technology to measure exercise-related hypertrabeculation in a general, non-athlete population. The results of the study have important practical implications because misdiagnosis of noncompaction cardiomyopathy in people who exercise regularly (whether professional athletes or amateurs) can trigger medical recommendations to stop physical exercise unnecessarily,” explained CNIC General Director Valentín Fuster.

The study, published today in The Journal of American College of Cardiology (JACC), forms part of the PESA-CNIC-SANTANDER study, whose principal investigator is Dr Valentín Fuster. PESA, begun in 2010 and recently renewed until 2030, is one of the most important cardiovascular prevention studies on the international stage. The 700 PESA participants included in the new substudy published in JACC will followed up throughout this period, allowing detailed analysis of the development, reversibility, and clinical implications of this heart adaptation to physical exercise.

“It is crucial to distinguish this benign adaptation to exercise from noncompaction cardiomyopathy, a disease with a genetic component that can have severe consequences, including heart failure, thromboembolism, arrhythmias, and sudden cardiac death,” said Dr Borja Ibáñez, Clinical Research Director at the CNIC, a cardiologist at Fundación Jiménez Díaz University Hospital, and leader of the JACC study.

In noncompaction cardiomyopathy, “the walls of the heart become thinner and the normally compact cardiac muscle is replaced by the spongy (trabecular) form, in direct contact with the interior of the ventricles,” continued Dr Ibañez.

The problem is that this disease is often diagnosed in young asymptomatic people, resulting in a medical recommendation to immediately cease physical activity that might cause sudden cardiac death. However, the presence of trabeculae is not always a sign of noncompacted cardiomyopathy. “Certain physiological situations, such as those resulting from high-intensity physical training or pregnancy, are known to trigger changes in heart structure similar to those seen in noncompacted cardiomyopathy,” explained Dr Ibañez.

Study first author and cardiologist José de la Chica explained that “it is essential to distinguish between the disease and the benign physiological adaptation, both to allow appropriate medical intervention to prevent disease progression and to avoid recommending healthy young people to unnecessarily avoid participation in sporting activities.”

The association between hypertrabeculation and high-intensity physical activity in professional athletes was already known. The key innovation of the new study is its combination of cardiac magnetic resonance (the gold standard diagnostic method for analyzing heart structure and function) with objective measures of physical activity. “We previously lacked information about whether physiological hypertrabeculation occurs in the general population or is restricted to elite athletes,” commented Dr Inés García-Lunar, an author on the study.

The study used cardiac magnetic resonance technology to assess accepted diagnostic criteria for noncompacted cardiomyopathy in more than 700 PESA-CNIC-SANTANDER study participants. These healthy Santander Bank workers have varying levels of physical activity, but none are professional athletes.

Physical activity was assessed objectively using accelerometers. These devices measure changes in movement speed in different body axes, and the participants wore them for week-long periods coinciding with each 3-yearly visit in the PESA protocol. Dr de la Chica explained that “this technology allowed us to classify individual physical activity as sedentary or as light, moderate, or vigorous exercise and to record the time spent in each type of activity during the week.”

The study showed that participants who routinely did vigorous exercise during the study period had larger hearts with more muscle mass. “These changes are typical of ‘athlete’s heart’ and are considered physiological,” said García-Lunar.

A more surprising finding was that a third of participants with a high level of vigorous physical activity (both men and women) met the diagnostic criteria for noncompaction cardiomyopathy, even though they were obviously healthy.

Previous studies had suggested that hypertrabeculation could simply be a consequence of the dilatation of the heart during intense physical exercise. “Thanks to the data from the PESA-CNIC-SANTANDER study, we have now shown that hypertrabeculation and dilatation are independent phenomena,” explained Dr de la Chica.

Key findings of the study are that none of the participants with trabeculated hearts showed signs of noncompaction cardiomyopathy and that all other test results were in the normal range.

The authors conclude that cardiac magnetic resonance criteria for diagnosing noncompaction cardiomyopathy should not be interpreted in isolation. Instead, imaging results should be placed in the context of other clinical parameters, genetic tests, and the level of physical activity. This is important even in a population of non-athletes in order to avoid misdiagnosis of the disease. Misdiagnosis can result in the unnecessary cessation of exercise, with all its associated negative physical and psychological consequences.

###

About the CNIC

The Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC), directed by Dr. Valentín Fuster, is dedicated to cardiovascular research and the translation of knowledge gained into real benefits for patients. The CNIC, recognized by the Spanish government as a Severo Ochoa center of excellence, is financed through a pioneering public-private partnership between the government (through the Carlos III Institute of Health) and the Pro-CNIC Foundation, which brings together 12 of the most important Spanish private companies.

Media Contact

Fátima Lois

[email protected]