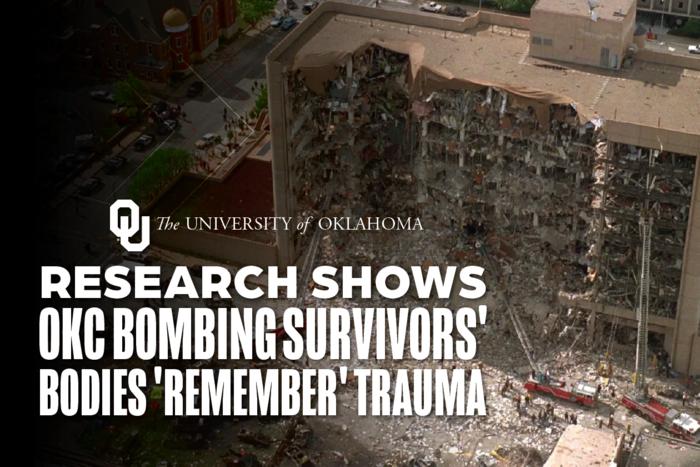

A recent groundbreaking study conducted by researchers at the University of Oklahoma reveals profound insights into the long-term effects of trauma on survivors of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. The research highlights an intriguing phenomenon where these individuals carry physiological markers of trauma, reflecting an imprint of their harrowing experiences, despite leading healthy and resilient lives post-event. This study illuminates the complex interplay between the mind and body, particularly how individuals can psychologically adapt and yet still harbor underlying biological stress responses.

Historically, various studies have focused on the psychological and biological consequences of trauma, particularly in survivors of terrorist attacks. However, the recent research stands out as the first comprehensive examination of multiple biological systems in individuals who have experienced the same traumatic event. This exploration into the survivors delves into cortisol levels, heart rate, blood pressure, and interleukins – all crucial components of the body’s stress response and immune system functioning.

Cortisol, often known as the body’s primary stress hormone, plays a pivotal role in regulating various bodily functions, including metabolism and the immune response. In a surprising twist, the findings showed that the average cortisol levels among the study’s participants were lower compared to a control group of individuals without such traumatic experiences. This counterintuitive result raises questions about the body’s adaptation mechanisms following severe stress and trauma.

Moreover, the study noted that while survivors exhibited higher blood pressure, their heart rate in response to trauma cues was significantly lower, indicating a potential blunting of their stress responses over time. This adaptation could suggest a complex psychological mechanism at work, wherein the mind learns to manage trauma, although the body might remain on high alert for future threats. These findings underscore a critical aspect of trauma research: the disparity between mental and physiological responses to traumatic stressors.

The research team measured two distinct interleukins to gain insight into the inflammatory responses among the survivors. Interleukin 1B, linked to inflammation, was found to be significantly elevated in the survivors. Conversely, interleukin 2R, which is generally associated with protective immune responses, showed diminished levels. These outcomes highlight a biological memory of the traumatic event, pointing toward potential long-term health implications for those directly affected by the tragedy.

Dr. Phebe Tucker, the lead author of the study, emphasized that while the minds of the survivors appear to have shown remarkable resilience, their bodies tell a different story. “The main takeaway from the study is that the mind may be resilient and able to set things aside, but the body does not forget,” Tucker stated. This dichotomy implores further investigation into how trauma can alter physiological processes, rendering the body a vessel of memories etched in stress biomarkers.

Interestingly, despite the identified stress responses in biological systems, participants did not exhibit elevated symptoms of depression or PTSD. The researchers discovered that the participants’ psychological well-being did not align with the stress biomarkers observed. This disconnect proposes a fascinating avenue for future research, as it suggests that individuals can function normally in their daily lives while harboring latent physiological responses to past traumas.

Tucker and her colleagues have an extensive history of studying the effects of the Oklahoma City bombing, with several investigations initiated shortly after the event. The temporal distance now afforded them a unique perspective, allowing them to compare data collected from the survivors seven years following the bombing. The current study expands upon earlier observations, emphasizing the need to examine not just psychological outcomes but also the biological ramifications of trauma.

As medical professionals continue to delve into the implications of this research, they may uncover critical insights into treating individuals impacted by trauma. The findings hint at potential long-term health concerns for survivors, reflected through elevated inflammatory markers despite their overt health status. Such revelations raise essential questions about ongoing healthcare support for trauma survivors, highlighting the need for a holistic approach to treatment that addresses both mental and physical dimensions of health.

Rachel Zettl, a co-author of the study, echoed Tucker’s findings, suggesting that the biological alterations in trauma survivors are not merely transient effects but rather lasting changes in their physical being. “It’s not just our minds that remember trauma; our biological processes do, too. It changes your actual physical being,” Zettl remarked. These observations could redefine approaches to understanding trauma, prompting a reassessment of how healthcare providers engage with survivors.

The comprehensive nature of this study, utilizing both psychological assessments and biochemical analyses, underscores the necessity for interdisciplinary approaches in trauma research. Future studies should aim to broaden this exploration, potentially assessing larger, more diverse populations to ascertain the universality of these findings and further understand the mechanisms underlying the body’s response to trauma.

In conclusion, the research spearheaded by the University of Oklahoma on the physiological effects of trauma among Oklahoma City bombing survivors illuminates critical intersections between mental health and biological stress markers. As our understanding of trauma deepens, it propels us toward a future in which both the psychological and physiological dimensions of trauma can be addressed holistically, thereby improving care and recovery outcomes for survivors everywhere.

Subject of Research: Physiological effects of trauma in Oklahoma City bombing survivors

Article Title: Learning from Hindsight: Examining Autonomic, Inflammatory, and Endocrine Stress Biomarkers and Mental Health in Healthy Terrorism Survivors Many Years Later

News Publication Date: 8-Jan-2025

Web References: DOI link

References: N/A

Image Credits: University of Oklahoma

Keywords: Trauma, Stress hormones, Cortisol, Interleukins, Oklahoma City bombing, Physiological psychology, Psychological stress, Health and medicine, Resilience, Inflammatory responses, PTSD, Survivor health.

Tags: biological stress responsescortisol levels and traumaeffects of terrorist attacks on healthgroundbreaking trauma researchimmune system functioning and traumalong-term effects of traumamind-body connection in traumaOklahoma City bombing survivorsphysiological markers of traumapsychological adaptation to traumatrauma imprints in survivorsUniversity of Oklahoma trauma study