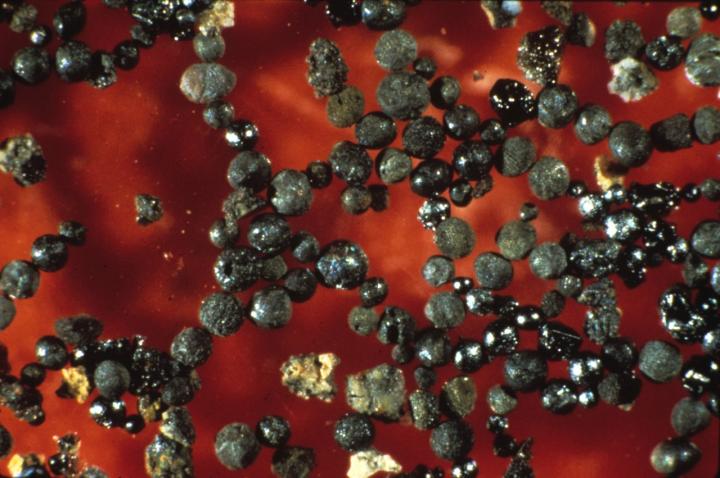

Credit: Donald Brownlee/University of Washington

Very occasionally, Earth gets bombarded by a large meteorite. But every day, our planet gets pelted by space dust, micrometeorites that collect on Earth’s surface.

A University of Washington team looked at very old samples of these small meteorites to show that the grains could have reacted with carbon dioxide on their journey to Earth. Previous work suggested the meteorites ran into oxygen, contradicting theories and evidence that the Earth’s early atmosphere was virtually devoid of oxygen. The new study was published this week in the open-access journal Science Advances.

“Our finding that the atmosphere these micrometeorites encountered was high in carbon dioxide is consistent with what the atmosphere was thought to look like on the early Earth,” said first author Owen Lehmer, a UW doctoral student in Earth and space sciences.

At 2.7 billion years old, these are the oldest known micrometeorites. They were collected in limestone in the Pilbara region of Western Australia and fell during the Archean eon, when the sun was weaker than today. A 2016 paper by the team that discovered the samples suggested they showed evidence of atmospheric oxygen at the time they fell to Earth.

That interpretation would contradict current understandings of our planet’s early days, which is that oxygen rose during the “Great Oxidation Event,” almost half a billion years later.

Knowing the conditions on the early Earth is important not just for understanding the history of our planet and the conditions when life emerged. It can also help inform the search for life on other planets.

“Life formed more than 3.8 billion years ago, and how life formed is a big, open question. One of the most important aspects is what the atmosphere was made up of — what was available and what the climate was like,” Lehmer said.

The new study takes a fresh look at interpreting how these micrometeorites interacted with the atmosphere, 2.7 billion years ago. The sand-sized grains hurtled toward Earth at up to 20 kilometers per second. For an atmosphere of similar thickness to today, the metal beads would melt at about 80 kilometers elevation, and the molten outer layer of iron would then oxidize when exposed to the atmosphere. A few seconds later the micrometeorites would harden again for the rest of their fall. The samples would then remain intact, especially when protected under layers of sedimentary limestone rock.

The previous paper interpreted the oxidization on the surface as a sign that the molten iron had encountered molecular oxygen. The new study uses modeling to ask whether carbon dioxide could have provided the oxygen to produce the same result. A computer simulation finds that an atmosphere made up of from 6% to more than 70% carbon dioxide could have produced the effect seen in the samples.

“The amount of oxidation in the ancient micrometeorites suggests that the early atmosphere was very rich in carbon dioxide,” said co-author David Catling, a UW professor of Earth and space sciences.

For comparison, carbon dioxide concentrations today are rising and are currently at about 415 parts per million, or 0.0415% of the atmosphere’s composition.

High levels of carbon dioxide, a heat-trapping greenhouse gas, would counteract the sun’s weaker output during the Archean era. Knowing the exact concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere could help pinpoint air temperature and and acidity of the oceans during that time.

More of the ancient micrometeorite samples could help narrow the range of possible carbon dioxide concentrations, the authors wrote. Grains that fell at other times could also help trace the history of Earth’s atmosphere through time.

“Because these iron-rich micrometeorites can oxidize when they are exposed to carbon dioxide or oxygen, and given that these tiny grains presumably are preserved throughout Earth’s history, they could provide a very interesting proxy for the history of atmospheric composition,” Lehmer said.

###

Other co-authors are Donald Brownlee, a UW professor emeritus of astronomy; Roger Buick, a UW professor of Earth and space sciences; and Sarah Newport, a former UW undergraduate who is now at Rutgers University. The research was funded by NASA, the UW Astrobiology Program, the UW Virtual Planetary Laboratory and the Simons Foundation’s Collaboration on the Origins of Life.

For more information, contact Lehmer at [email protected] or Catling at 206-543-8653 or [email protected].

Media Contact

Hannah Hickey

[email protected]

206-543-2580

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.