Natural selection has produced mammals that age at dramatically different rates. Take, for example, naked mole rats and mice; the former can live up to 41 years, nearly ten times as long as similar-size rodents such as mice.

Credit: University of Rochester illustration / Julia Joshpe

Natural selection has produced mammals that age at dramatically different rates. Take, for example, naked mole rats and mice; the former can live up to 41 years, nearly ten times as long as similar-size rodents such as mice.

What accounts for longer lifespan? According to new research from biologists at the University of Rochester, a key piece of the puzzle lies in the mechanisms that regulate gene expression.

In a paper published in Cell Metabolism, the researchers, including Vera Gorbunova, the Doris Johns Cherry professor of biology and medicine; Andrei Seluanov, professor of biology and medicine; and Jinlong Lu, a postdoctoral research associate in Gorbunova’s lab and the first author of the paper, investigated genes connected to lifespan. Their research uncovered specific characteristics of these genes and revealed that two regulatory systems controlling gene expression—circadian and pluripotency networks—are critical to longevity. The findings have implications both in understanding how longevity evolves and in providing new targets to combat aging and age-related diseases.

Comparing longevity genes

The researchers compared the gene expression patterns of 26 mammalian species with diverse maximum lifespans, from two years (shrews) to 41 years (naked mole rats). They identified thousands of genes related to a species’ maximum lifespan that were either positively or negatively correlated with longevity.

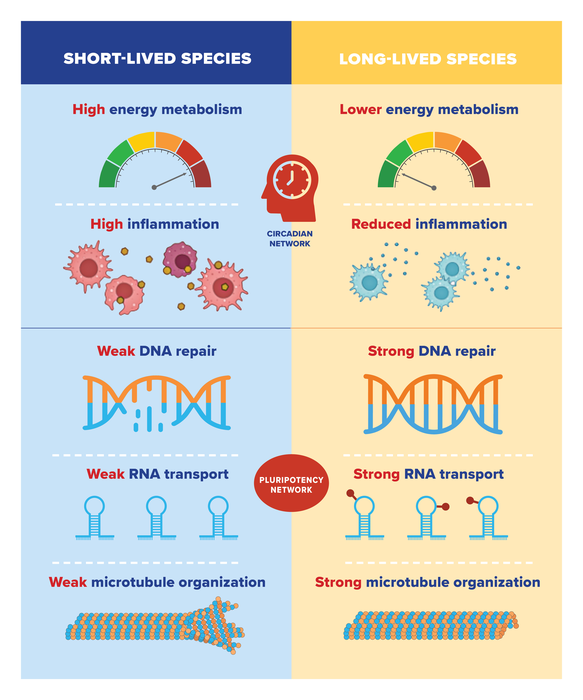

They found that long-lived species tend to have low expression of genes involved in energy metabolism and inflammation; and high expression of genes involved in DNA repair, RNA transport, and organization of cellular skeleton (or microtubules). Previous research by Gorbunova and Seluanov has shown that features such as more efficient DNA repair and a weaker inflammatory response are characteristic of mammals with long lifespans.

The opposite was true for short-lived species, which tended to have high expression of genes involved in energy metabolism and inflammation and low expression of genes involved in DNA repair, RNA transport, and microtubule organization.

Two pillars of longevity

When the researchers analyzed the mechanisms that regulate expression of these genes, they found two major systems at play. The negative lifespan genes—those involved in energy metabolism and inflammation—are controlled by circadian networks. That is, their expression is limited to a particular time of day, which may help limit the overall expression of the genes in long-lived species.

This means we can exercise at least some control over the negative lifespan genes.

“To live longer, we have to maintain healthy sleep schedules and avoid exposure to light at night as it may increase the expression of the negative lifespan genes,” Gorbunova says.

On the other hand, positive lifespan genes—those involved in DNA repair, RNA transport, and microtubules—are controlled by what is called the pluripotency network. The pluripotency network is involved in reprogramming somatic cells—any cells that are not reproductive cells—into embryonic cells, which can more readily rejuvenate and regenerate, by repackaging DNA that becomes disorganized as we age.

“We discovered that evolution has activated the pluripotency network to achieve longer lifespan,” Gorbunova says.

The pluripotency network and its relationship to positive lifespan genes is therefore “an important finding for understanding how longevity evolves,” Seluanov says. “Furthermore, it can pave the way for new antiaging interventions that activate the key positive lifespan genes. We would expect that successful antiaging interventions would include increasing the expression of the positive lifespan genes and decreasing the expression of negative lifespan genes.”

Journal

Cell Metabolism

DOI

10.1016/j.cmet.2022.04.011

Article Title

Comparative transcriptomics reveals circadian and pluripotency networks as two pillars of longevity regulation

Article Publication Date

16-May-2022